As superbugs grow in strength and number, Nova Scotia health professionals are urging the public to take a second look at their use of antibiotics.

Superbugs are micro-organisms — bacteria, viruses and fungi — that have evolved to resist common antibiotics, and experts say overusing the drugs can help superbugs develop resistance to them.

“The common scenario and one we get called about quite frequently is patients who have a urinary tract infection in the community and there’s no oral antibiotics that are effective against that bacteria,” said Dr. Paul Bonnar, an infectious disease physician with the Nova Scotia Health Authority (NSHA).

“So that would require patients getting an intravenous antiobiotic, which is costly, associated with more side effects and could potentially lead to the patient requiring to come into the hospital or emergency department.”

READ MORE: How superbugs and antibiotic resistance will make common medical procedures harder

The push for discerning drug use comes in the wake of a new report suggesting that in the next three decades, the evolution of superbugs may put some of the treatments we take for granted — like caesarian sections and organ transplants — at risk as it becomes harder fight off infection.

Commissioned by the federal government, “When Antibiotics Fail” estimated that by 2050, around 40 per cent of infections could be resistant to first-line antibiotics, contributing to the possible deaths of 400,000 Canadians at the hands of drug-resistant infection.

“If things do not change as far as resistance goes, we could certainly be looking at a situation where routine surgeries are impossible, or associated with higher surgical site infections, and chemotherapy becomes difficult because we can’t prevent those infections in patients without immune systems,” said Bonnar.

Get weekly health news

“So it really will affect all areas of medicine and that’s why we get very concerned about anti-microbial resistance, because it’s not just one niche of medicine.”

The report predicted serious economic consequences, as well: $120 billion in hospital expenses and $388 billion in gross domestic product over the next 30 years.

But health care professionals say patients can play a role in preventing such a future. Taking measures to avoid getting sick in the first place — like washing hands and getting vaccinated — are helpful, as are keeping your antibiotics away from friends and relatives, and ensuring antibiotics are really necessary next time they’re prescribed to you.

According to Bonnar, between 30 and 50 per cent of antibiotics prescriptions aren’t used correctly.

“No doubt antibiotics are often needed,” he told Global News. “But I think for patients and health care workers, if we could think twice about antibiotics… recognizing that antibiotics have significant and frequent side effects, so antibiotics aren’t used for just in case scenarios and that we’re using them when needed.”

READ MORE: How Canada ‘dropped the ball’ on drug-resistant infections

Carolyn Mitchell, a nurse practitioner and assistant professor in the nursing school at Dalhousie University, agreed. She recommended, “… Having honest and open conversations with their health care provider about when they’re feeling unwell.”

“Sometimes time will help cure things, and sometimes it just takes time to know when an antibiotic is actually in order.”

Examples of circumstances where that may be the case are sinusitis, ear and throat infections, she added.

READ MORE: Superbugs to kill nearly 400,000 Canadians by 2050, report predicts

As it stands, both the federal government and the province are developing superbug action plans that focus on research to treat and prevent infection, the surveillance and improvement of antibiotic use, and the study of the superbugs themselves.

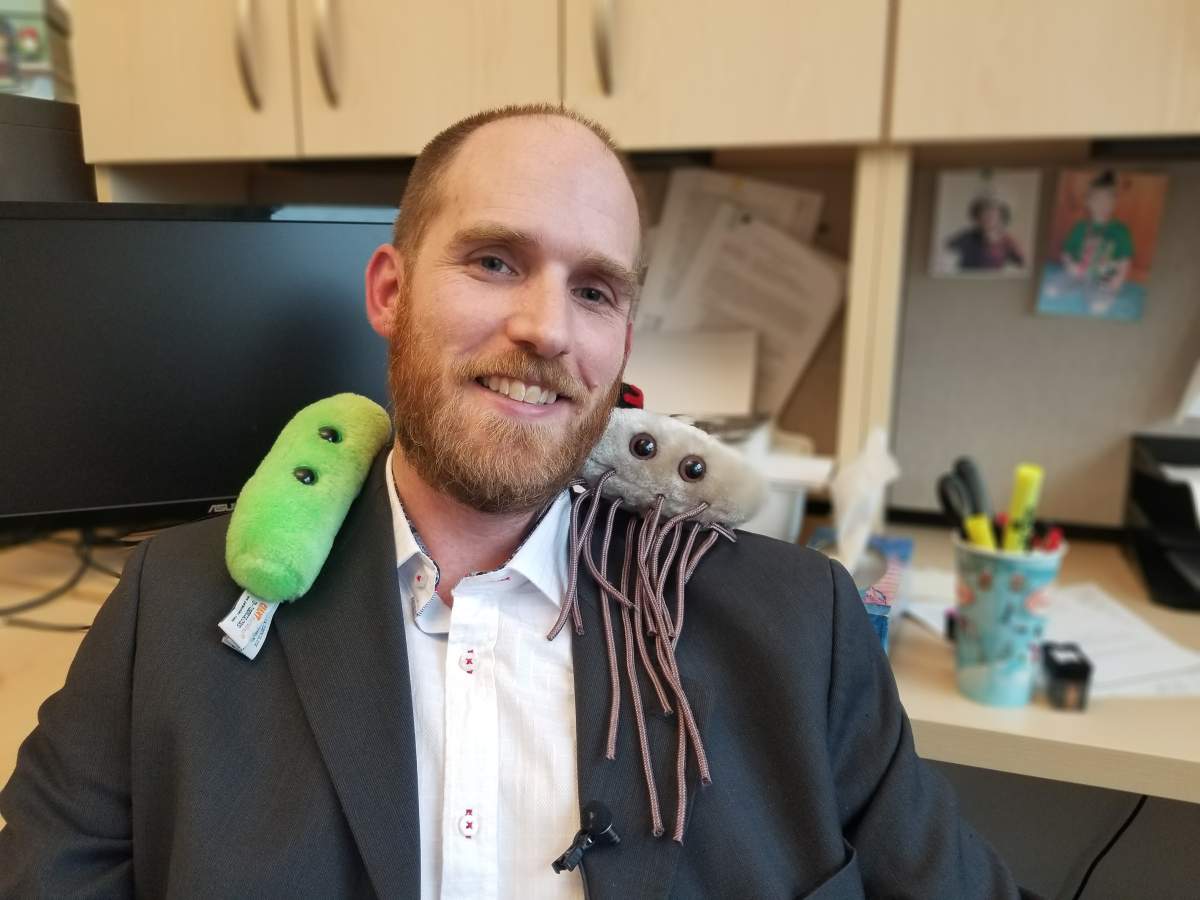

Dalhousie University’s Robert Beiko and his team are working on software that identifies the genes that make superbugs resistant. Eventually, the bacterial genomicist hopes to have the capacity to take patient samples and analyze their superbug DNA with quick turnaround for doctors.

“Once we find those, we can say, ‘Alright, what’s the consequence of that? What is the bacterium going to be able to do if it comes into a patient and we try to treat them with vancomycin, or penicillin or anything like that?” he explained.

“… You can actually inform decision-making and say, ‘We see resistance to this antibiotic, don’t treat with that because it’s not going to help, it’s only going to make the situation worse.”

— With files from Leslie Young and The Canadian Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.