Leona Peterson doesn’t drink the water from her tap anymore.

The single mother says she was warned about lead in the water by a neighbour as soon as she moved into the subsidized Indigenous housing complex where she lives in Prince Rupert, a city of almost 12,000 people in northwestern B.C.

“She said, ‘There is lead in our water,’” Peterson said. “‘Don’t doubt it, just start flushing.’”

For years, Peterson’s eldest son’s daily chore was preparing the family’s water for drinking and cooking by “flushing” the pipes –– running the tap water for five to 10 minutes –– before filling a four-litre jug.

Now, Peterson buys large jugs of water instead. Even after it’s flushed she doesn’t trust the water from her tap.

Reporters from the University of British Columbia, as part of an investigation by a national consortium of universities and media companies, including Concordia University’s Institute for Investigative Journalism, Global News and Star Vancouver, tested water samples from Peterson’s kitchen in December. An accredited lab measured 15.6 parts per billion (ppb) of lead in her water — three times Health Canada’s guideline.

- After tragedy, Lapu Lapu victims were victims of ‘snooping’ at hospitals: report

- Rockslide closes Highway 93 between B.C. and Alberta until at least noon on Thursday

- $10-a-day daycare program paused in order to stabilize, B.C. government says

- B.C. Office of the Seniors Advocate addresses impact of 2026 provincial budget

Water from her kitchen tap also exceeded federal guidelines for lead in tests taken in February and July.

“To find out that it’s as high as it is scares me,” she said. “This is lead, this is a poison.”

Peterson isn’t alone. Eighty-four per cent of the 25 homes sampled in Prince Rupert for this investigation exceeded the federal guideline for lead in drinking water.

Coastal B.C.’s rainy climate can produce naturally acidic surface water. Left untreated, it can corrode pipes and plumbing, leaching metals into drinking water.

Despite federal guidelines recommending corrosion control and monitoring, some municipalities aren’t taking steps to combat corrosive water or testing for lead at the tap in private homes. Residents are being left in the dark about the safety of their water.

For years, that was the case in Prince Rupert.

The city and Northern Health, which provides healthcare in northern B.C., are taking steps to minimize exposure to lead-contaminated drinking water.

“It’s definitely something that we’re taking seriously,” said Dr. Raina Fumerton, the health authority’s acting chief medical health officer.

“Safe, potable drinking water is something that everyone in Canada should be able to expect,” she said.

“Unfortunately, there was a period of time where lead was commonly used as part of the plumbing infrastructure.”

Officials with the City of Prince Rupert say there are no municipal lead service pipes, delivering water to homes or businesses, as there are in Toronto, Montreal and Regina, for instance.

The water itself “tests well below” Health Canada’s guideline before it hits the property line, after which the city says it “is not responsible for water service infrastructure on private property.”

Prince Rupert’s corrosive water does increase the risk of lead leaching from plumbing fixtures and solder, which is used to join pipe, in older homes. That’s a problem the city’s planned water treatment plant will eventually help address.

In the meantime, the city has told residents to protect themselves, by replacing plumbing that may contain lead, installing filters or flushing pipes until the water runs noticeably colder before drinking.

In the spring of 2018, the city mailed a flyer to every household with these tips. This summer, after undertaking its own lead testing, the city issued another press release and video, in which Mayor Lee Brain reminds residents to take steps to reduce the risk of lead exposure.

“We take the health and safety of our residents very seriously, which is why the water supply has been the top priority of city council since we took office at the end of 2014,” Brain says in the video, referencing a multi-million dollar effort to upgrade the city’s century-old water system.

Health Minister Adrian Dix said the issues in Prince Rupert have been known for a “considerable period of time.”

“It’s a significant issue, and we take it seriously. I believe what you do when you’re faced with a problem is you start to deal with it. And that’s what we’re trying to do.”

Dix said Northern Health and the City of Prince Rupert are “doing the right thing.”

“They can be criticized, and we can be criticized for not moving fast enough and so on, and I accept that. But specific action has been taken in the last short period, and we’ll continue to be taking it,” he said.

No safe level of lead

From British Columbia to Nova Scotia, reporters involved in this nationwide investigation found lead in tap water at levels well beyond Health Canada’s guideline of 5 ppb. According to the World Health Organization, there is no safe level of lead.

Get weekly health news

The health effects of long-term exposure to lower lead levels range from learning disabilities to hypertension. Babies, children under the age of six, pregnant women and developing fetuses are most vulnerable to the neurotoxin, which accumulates in the body over time.

Blood lead levels have declined significantly in Canada as lead was reduced in paints, gasoline and other products but research has found long-term exposure to even relatively small amounts of lead can have major health consequences.

In March, Health Canada decreased the maximum allowable concentration of lead in drinking water to 5 ppb from 10 ppb and recommended that lead concentrations be kept “as low as reasonably achievable.”

“In the long-term, it should definitely be less than one part per billion, but it’s going to take us time to get there,” said Bruce Lanphear, a health sciences professor at Simon Fraser University and an expert on lead toxicity.

In December, February and July, reporters from the University of British Columbia collected samples of tap water from homes in Prince Rupert and had them analyzed at an accredited lab.

Twenty-one out of the 25 homes exceeded the federal guidelines at least once in “first draw” samples collected after the plumbing hadn’t been used for at least six hours.

One result came in at 70 ppb, 14 times higher than Health Canada’s guideline.

Low-income families are most at-risk

In Prince Rupert, residents were shocked by the results.

“I’m disturbed,” said Sandra Jones, a retired superintendent of the Prince Rupert School District. Water from her kitchen tap showed a lead level of 11.5 ppb. “I’m glad I don’t have children living in my home.”

In 2016, Jones found herself the centre of media attention when elevated levels of lead were discovered in the drinking water at some of the city’s schools.

“Once we knew, we were on it,” she said.

Maintenance staff flushed the pipes each morning, students and families were notified, pipes were replaced, filters were installed and some drinking water fountains were shut down.

From her living room overlooking downtown Prince Rupert and the sea beyond, Jones said despite that experience, she has always been proud of the city’s drinking water.

“It’s kind of cloudy and it looks funny, but it’s very, very good water,” Jones said. “But when it sits in these old pipes, it leaches the lead out.”

Jones and her husband have replaced some of the plumbing in their 1959 home, but the results surprised her. She’s concerned there are others in her community who have it even worse.

“It does, I’m absolutely certain, disproportionately affect the poor in this community.”

Low-income neighbourhoods are usually in older parts of the city where infrastructure is aging, said Michèle Prévost, a civil engineering professor at Polytechnique Montréal and an expert in the field of water contamination. “Your socioeconomic status affects your blood lead level,” she said.

As a renter in subsidized housing, Peterson said she feels decisions about plumbing and infrastructure improvements are out of her control.

“I live in poverty,” she said. “I’m at the bottom — I have no say.”

Northern Health’s Fumerton agrees that people with lower incomes are at higher risk.

“For the lower-income populations, simply saying, you need to change out your pipes, it’s not really fair,” she said. That’s why the city is working on an engineered solution to reduce corrosion, she added.

In the meantime, the city doesn’t subsidize filters for affected residents. Instead, officials recommend flushing the pipes, which Lanphear calls reasonable in the short-term.

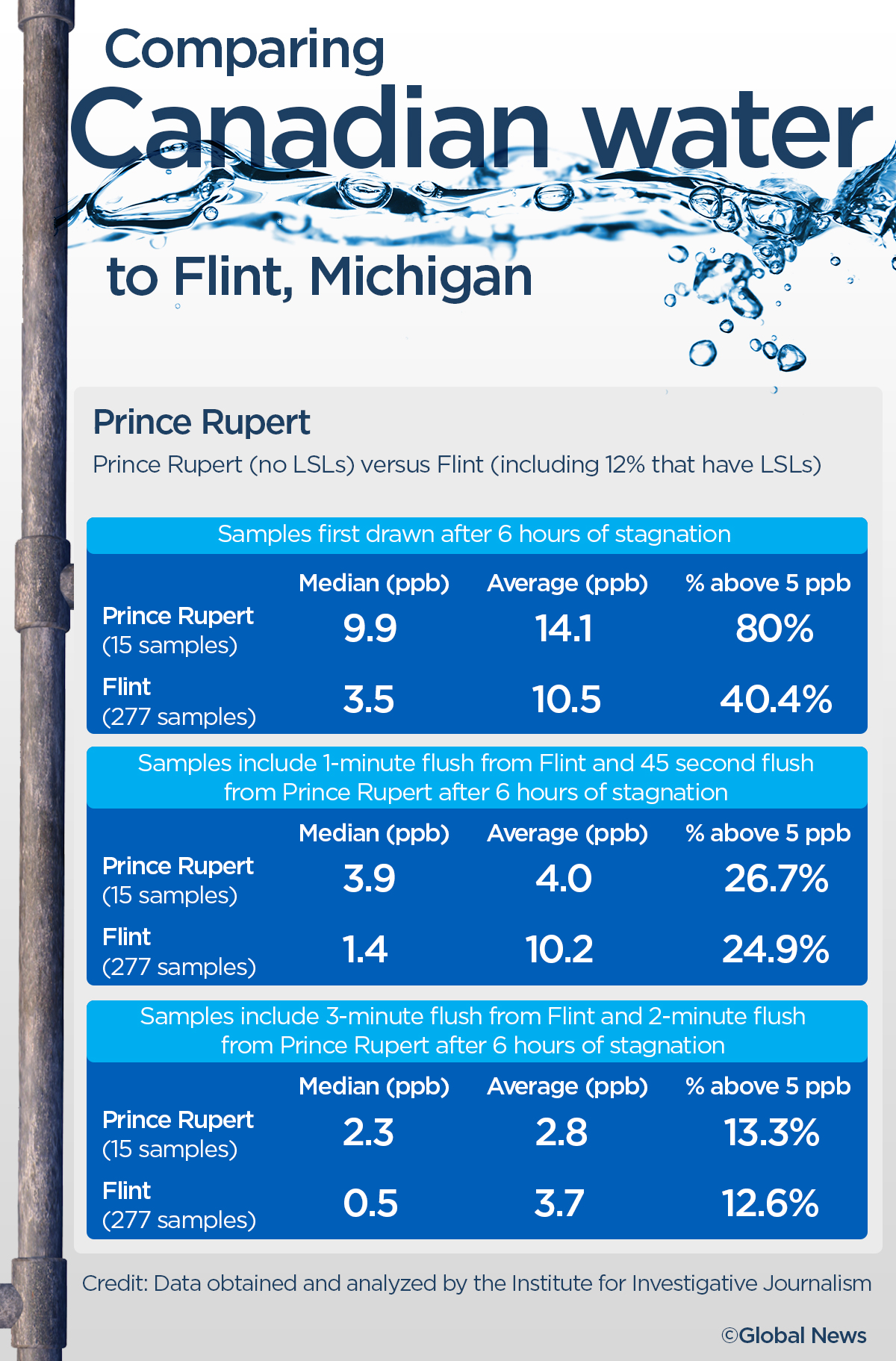

Of the 15 homes tested as part of this investigation in July, 12 exceeded Health Canada’s guidelines for lead in first draw tests. Samples from four of 15 homes exceeded the guidelines after the water was flushed for 45 seconds. Two exceeded the guideline after a two-minute flush.

“But if you’ve ever sat and waited two minutes for water to flush before you use it… it’s extraordinarily long,” said Lanphear. “It’s not a viable solution. We really need to get some filters in place to protect people.”

‘It really is insidious’

Residents such as Nikida Bolton and her partner Colin Innis, who live in the same housing complex as Peterson, have stopped relying on the water that pours from their kitchen tap.

When they learned about lead levels at some local schools in 2016, including the one attended by their young son, the family started buying big jugs of bottled water.

Bolton was pregnant with their youngest daughter when samples taken by reporters found levels of lead at 10.2 ppb in the water from their kitchen faucet.

“We don’t use the water for her at all,” said Bolton. “We always use the bottled water for her formula.”

It’s a decision that could help protect her youngest child from some of the worst impacts of lead. Babies who are fed formula mixed with tap water are particularly vulnerable to the risks of lead in drinking water, said Lanphear.

Peterson, whose youngest is six, is also worried about the potential impacts on her children. Lanphear said the levels detected in her water would be high enough to increase a child’s risk of developing ADHD with chronic exposure.

Based on some of the higher lead levels found by reporters in Prince Rupert, Lanphear said, “It’s a little harder to measure, but we would also expect to see an increase in the risk of hypertension, and even premature death from coronary heart disease among adults who are chronically exposed to these levels.”

“Chronic low-level exposure” can have serious consequences for health. “It really is insidious,” he said.

“We don’t see (it) unless we test children. We don’t see that they might be lead poisoned. Although later in life, like when they start school, the teacher and the parents may recognize that the kids (are) really struggling, having a hard time learning, can’t pay attention, acting out, those kinds of things,” he said.

‘Unheard of in America’

In February 2018, Northern Health began requiring the city to inform residents about lead and how to protect themselves.

The city was also required to assess corrosion in residential plumbing through a field sampling program.

Testing conducted by the city and Northern Health this year found lead levels above Health Canada’s guideline at 41 of 65 homes sampled.

These were also “first draw” tests. In a press release the city notes, “these levels are not representative of the water being drawn through the tap throughout the day once stagnant water has cleared.”

Eleven of those homes also exceeded the provincial government’s “action level” of 15 ppb, signalling a corrosion risk and triggering a second round of sampling that’s now underway.

Prince Rupert shows lead levels higher than the new 5 ppb guideline “can be frequently found in systems without corrosion control because of the presence of legacy solders and leaded brass,” Prévost said, in an email.

A 1991 government report shows the provincial government has known for at least 28 years that some coastal municipalities have acidic water.

Acidic water, which has a pH below 7, is considered a significant factor in the corrosion of metal pipes and solder. Yet, there are no federal or provincial rules in B.C. that require water providers to address it.

From Lanphear’s perspective “corrosion controls should have been implemented 20 to 30 years ago.”

While the U.S. regulates monitoring and corrosion control, Health Canada provides voluntary guidelines that provinces may choose to implement.

Some communities take steps to address corrosive water at the treatment plant before it’s distributed into residents’ homes, others don’t.

Metro Vancouver, for instance, began adding lime to raise its water’s pH in 2011.

Across the harbour from Prince Rupert, Metlakatla First Nation, a community of around 120 people, filters its water through limestone.

Prince Rupert does not plan to take any pH-boosting measures until its new water treatment plant is built.

Between January 2017 and January 2019, pH levels ranging from 5.3 to 6.7 were detected in city water samples from the distribution system.

One sample from January 2019 had a pH of 5.6, low enough that it “would be unheard of in America,” said Marc Edwards, a professor at Virginia Tech who helped expose the corrosion problem in Flint, Michigan.

“It’s so inexpensive to raise the pH, which would … lower levels of copper, lower levels of lead,” he said.

Fumerton said it’s not quite as simple as adding something to the water.

“They need to do studies to ensure that the choice that they’re making is actually going to be effective for their particular, unique scenario,” she said, adding that infrastructure changes will be needed to address whatever solution they choose.

The new treatment plant won’t completely resolve the issues with lead, said Mayor Brain in a city video. He did not agree to an interview.

“If there weren’t sources of lead in the residential plumbing it wouldn’t get into the water, which is why we encourage people where possible to consider replacing all plumbing components containing lead or conduct flushing,” he said.

Prince Rupert isn’t alone in its struggle with corrosive water.

Several other water providers serving coastal B.C. communities have reported drinking water with acidic pH and low alkalinity in annual reports and some do not appear to be adjusting the water’s pH in order to control corrosion.

Prévost said “it’s the worst combination for lead and copper.”

The challenge can be difficult to solve for smaller, more remote communities.

“Many other communities across the north struggle with their drinking water system. They’re outdated and need upgrades, but those upgrades are extremely expensive,” said Fumerton.

In March 2016, members of the B.C. Environmental Health Policy Advisory Committee discussed the “best approach … to encourage communities to implement corrosion control,” according to meeting minutes obtained under Freedom of Information legislation.

However, despite discussing the “need (for) a clear, consistent message” and concerns about leaching even in regions where the pH is not acidic, the province has not required municipalities to control corrosion or to conduct in-home testing in a random selection of homes, documents show.

Dix said requirements for in-home testing and corrosion control are something to be considered.

“The issues in all those communities on the coast have to be taken seriously,” he said.

The province does require schools built before 1990 to test for lead in drinking water once every three years. Government data shows that since 2016 more than 600 schools have reported at least one water sample that exceeded the national guideline for lead.

Health Canada recommends lead testing at residential taps as well, but provincial governments decide if municipalities will be required to do so.

Drinking water officers in B.C.’s regional health authorities can add this requirement to municipalities’ operating permits, but it’s not mandated across B.C.

The resulting lack of data makes it difficult to know which communities may be at-risk or whether corrosion control already in place is effective.

“The first step is to assess if you have an issue with lead, and if you have an issue with lead you have to correct with treatment,” Prévost said.

Lead exceedances were also found in homes in Vancouver, Nanaimo and Victoria, suggesting a broader problem — and it goes beyond lead.

Lack of accountability

In July, B.C.’s auditor general, Carol Bellringer, released the results of an audit assessing the protection of drinking water in the province.

She found a convoluted system involving 23 pieces of legislation, multiple ministries and agencies — and a lack of accountability.

Though it was too early to assess whether the government’s guidance on lead was being implemented, the audit determined overall that, “(the Ministry of Health) and the (Provincial Health Officer) are not taking the needed action to protect drinking water for all British Columbians.”

Dix said the Ministry of Health is working to implement all of the auditor’s recommendations.

He did not, however, make any firm commitments to require provincewide lead testing or requirements for corrosion control.

Lanphear, an expert on lead toxicity, said governments should aim to lower exposure as a preventative measure — particularly since heart disease is the leading cause of premature death worldwide.

“We don’t invest in public health the way we should, we’ve ignored this water infrastructure for too long,” he said.

Prévost said the guidelines aren’t being taken seriously enough.

“If you don’t measure, you don’t know if you have a problem,” she said. But, “if you don’t have regulations, why would the utilities measure? And if you don’t have a regulation that says, when it’s high you have to act, why would anybody act?”

with files from Paul Johnson, Global News

Credits: Faculty Supervisor: Charles Berret, University of British Columbia, Graduate School of Journalism

Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University: Series Producer: Patti Sonntag Research Coordinator: Michael Wrobel; Project Coordinator: Colleen Kimmett; Investigative Reporting Fellow: Lauren Donnelly

Institutional Credits: University of British Columbia, Graduate School of Journalism

Produced by the Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University

See the full list of Tainted Water series credits here: concordia.ca/watercredits.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.