Lead levels in the tap water of some parts of Montreal are as high as those in Flint, Michigan, at the peak of their water crisis in 2015, says a senior city official.

The official confirmed the numbers from thousands of water test results obtained during a joint investigation by Global News, The Toronto Star, Le Devoir and Concordia’s Institute for Investigative Journalism.

But municipal and provincial government officials both say that Montreal’s water is safe and that the situation in the metropolis is different than the crisis that struck the American city.

Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante has also introduced new measures to remove lead from the city’s tap water in the wake of this investigation’s findings. Among the changes will be a requirement for all underground lead pipes to be replaced, on both sides of the property line.

She told Global News in an interview that Montreal would do the work and bill the owners for their own portion of the replacement, giving households 15 years to pay the bill. The city is also offering free filters to households with high lead levels in their tap water, as well as introducing a new website that will allow people to search to see if their address might have a lead problem.

Flint’s crisis sprang from a decision to draw water from a more corrosive water source into an old and deteriorating lead pipe infrastructure.

The result was a perfect public health storm.

Headlines around the world highlighted not just lead-contaminated drinking water but the deaths of 12 people from a Legionnaire’s outbreak, as bacteria spread through the water system.

Montreal has tens of thousands of lead service lines underground that link its water mains to the homes of nearly 300,000 people, according to city estimates. As a result, these residents in houses or apartment buildings with eight dwellings or less are at risk of getting traces of the neurotoxin mixed into the water, every time they open their taps.

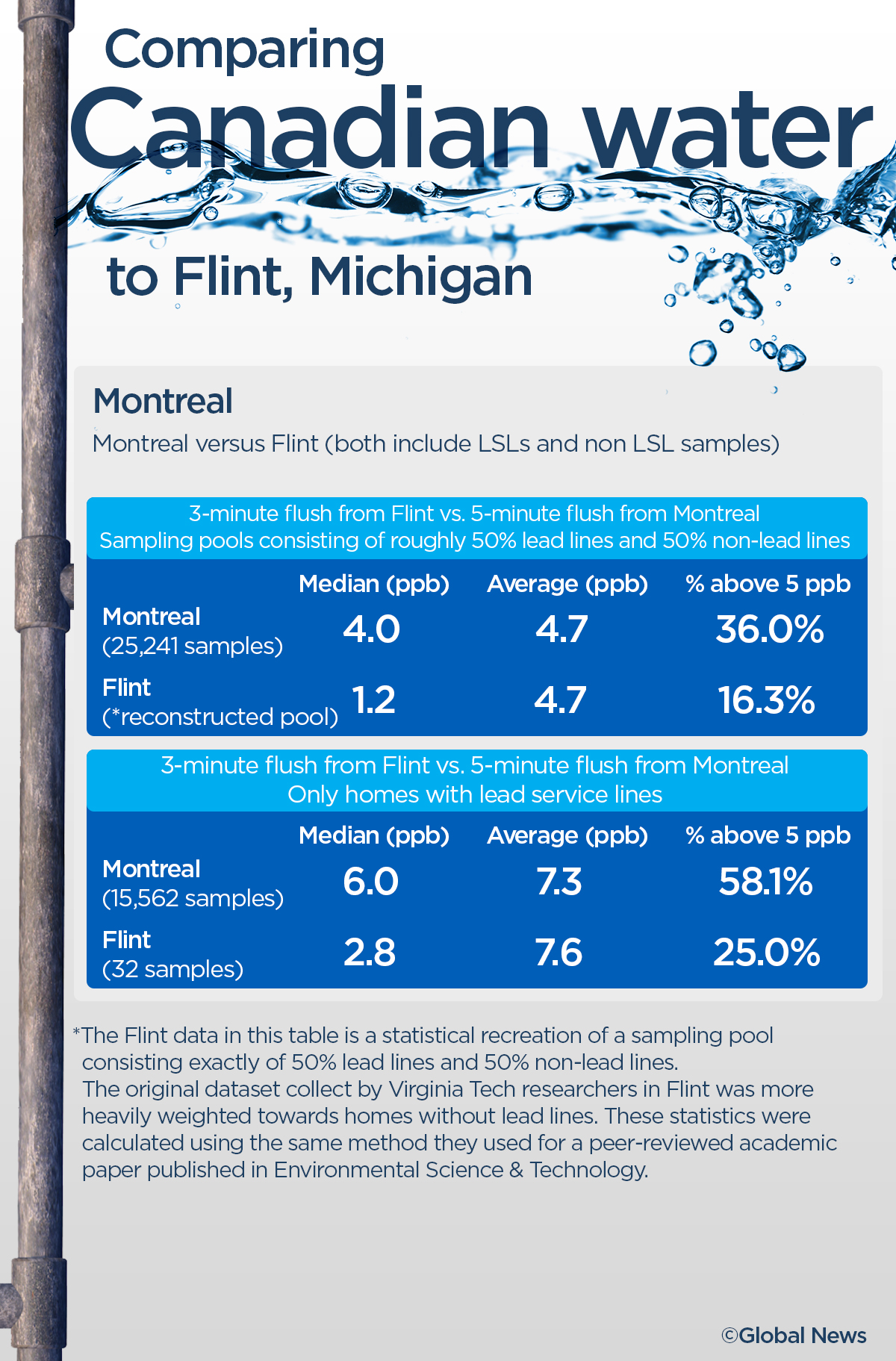

Overall, testing results from Montreal obtained by the Institute for Investigative Journalism through freedom of information legislation reveal 58 per cent of the water samples from homes with lead pipes had lead levels above Canada’s recommended drinking water limit of five parts per billion (ppb) of lead. This was after city technicians flushed the taps for five minutes. In Flint, only 25 per cent of the samples taken after a three minute flush from homes with lead pipes were above that limit in 2015.

“I think the comparison is sound,” said Michèle Prevost, a civil engineering professor at the Polytechnique engineering school who specializes in research on water quality.

In addition, the average amount of lead in flushed samples of water, taken by Montreal technicians after the tap was running for five minutes in homes with lead service lines was 7.3 ppb in Montreal. In Flint, the average water sample for homes with lead service lines, taken after a three-minute flush, measured 7.6 ppb of lead.

Get daily National news

Engineer Marc Edwards, a professor of environmental and civil engineering at Virginia Tech who helped expose the water crisis in Flint, Mich., in 2015, sees parallels in the numbers between the two cities.

“These samples from Montreal with a five-minute flush are definitively worse than a three-minute flush from Flint because you flush longer and you still have more lead,” Edwards said in an interview.

Montreal says its water is fine, but the pipes are the problem.

“Montreal’s case is not the same as Flint,” said Chantal Morissette, Montreal’s Director of Water Services. “In Montreal, the water is safe. The water that is coming from the drinking water plant is of excellent quality. The water that is in the pipes is excellent. It’s only when it goes through the lead service lines and yes, some of the results are as high.”

“They started early with interventions and characterize very precisely the nature of the problem. They informed the citizens to make sure they had the right information to protect themselves when they had lead service line onto their house,” she said.

Some Montreal residents disagreed.

Stephanie St. Onge, 46, was told by the city that her water contained 6 ppb of lead. An independent test commissioned by the Institute for Investigative Journalism revealed a tap water sample from her NDG home had 16 ppb of lead, nearly three times more than what the city found.

“The information is wrong. They treat it like it’s nothing.”

As part of this investigation, journalism students from Concordia University visited 23 households that had previously had their water tested by the city and agreed to have an independent test.

The students then collected water samples and sent them to an independent lab for testing. The results revealed that 13 out of the 23 had lead levels higher than what the city had told the residents.

READ MORE: Montreal Mayor Valérie Plante will require households to replace lead water pipes

Experts such as Prévost said the discrepancy may have been caused by the sampling method used under provincial regulations, which require municipalities to flush taps for five minutes before collecting a sample. This type of method flushes out water that is sitting in lead pipes, replacing it with fresh water from the city’s network that is less likely to be contaminated from the lead service lines.

Plante sought to reassure Montrealers who feel they were misled.

“Again, I will never question how people would feel about that because I would understand that they’re worried,” Plante said.

“That being said, the fact is that Montreal has always been proactive and responsible in how we manage water. Let’s not forget, throughout the years, science has evolved, even what governments are deciding to do evolves. The City of Montreal has always been, not only following the protocol of Quebec, of course, but working with (scientists).”

Over 15 years, lead test results in Montreal, using the method that requires flushing the taps, revealed that there were more than 9,000 samples that were higher than the new federal limit of 5 ppb. Some of these exceedances include lead levels of 72 ppb in a 1928 two-storey row house in Ahuntsic, 60 ppb in a classic wartime home in Rosemont and 54 ppb in a mid-century bungalow in Nouveau-Bordeaux.

Residents can use a filter to get the led out of the water if it is certified under the NSF/ANSI Standard 53 or 58.

But the high results in Montreal have led some residents to switch to bottled water.

“We don’t use the tap water for drinking or brushing our teeth or anything like that,” she explained.

A recent sample collected by Concordia journalism students showed her tap water contained five times more lead than Health Canada deems acceptable.

“In 2019, it’s very surprising,” she said.

While some Canadian cities have implemented a common fix, Montreal has taken a different approach. When the City of Montreal asked Marc Edwards for advice back in 2006, he recommended adding a non-toxic substance to the water to control corrosion.

“We did recommend that enhanced corrosion control could probably reduce those lead levels by at least 50-60 per cent beyond what they’re currently achieving,” the Virginia Tech engineer said.

But the city rejected that advice, which he noted would not have happened in the United States, under its existing federal legislation.

“If it were an American city that would not have been allowed, they would have to had to implement corrosion control,” Edwards said. “But Canada’s only into this game about 10 years, whereas in the U.S., we’ve got 30 years of failures that we’ve learned from. Perhaps their response could have been faster or maybe it’s a judgment call.”

READ MORE: Investigation reveals dangerous lead levels in some Quebec drinking water

When Toronto implemented corrosion control in 2014, Edwards says lead levels went down 90 per cent.

Today, Montreal has decided to focus on getting rid of all the lead pipes rather than treating the water, noting that scientific research shows that orthophosphate might not be as effective on homes that have partial lead service line replacements on only one side of the property line.

“We’re just going to shift gears, take a new approach,” the mayor said.

In July, Plante’s office told Global News that it would get rid of tens of thousands of lead pipes in the city by 2026. Now the city says its new target is 2030, four years behind schedule.

Story by:

Mike De Souza and Dan Spector — Global News

Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University

Le Devoir

Brigitte Tousignant, Ian Down, Miriam Lafontaine — Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University

The Toronto Star

Robert Cribb

Investigative reporting team, Concordia University:

Michael Bramadat-Willcock

Mia Anhoury, James Betz-Gray, Thomas Delbano, Elaine Genest, Adrian Knowler, Mackenzie Lad, Benjamin Languay, Franca Mignacca, Jon Milton, Matthew Coyte, Katelyn Thomas, Ayrton Wakfer

Production team, Le Devoir:

Project editor: Veronique Chagnon

Reporters: Annabelle Caillou, Améli Pineda

Intern: Lea Sabbah

Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University:

Series producer and faculty supervisor: Patti Sonntag

Research coordinator: Michael Wrobel

Project coordinator: Colleen Kimmett

Produced by the Institute for Investigative Journalism, Concordia University

See the full list of “Tainted Water” series credits here: concordia.ca/watercredits

Comments