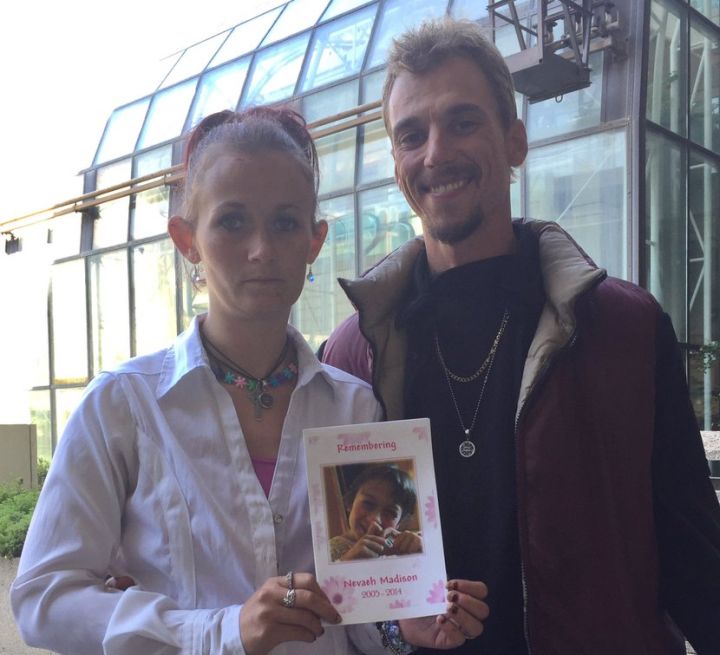

An inquiry into the 2014 death of an eight-year-old girl at an Edmonton group home has resulted in three recommendations on the use of chloral hydrate, one of which states the substance is not an appropriate drug for long-term use to help children sleep.

Nevaeh Michaud died on Jan. 5, 2014 at Ayesha’s Light, a group home in south Edmonton operated by Mariam’s Footsteps. A toxicology report later found Michaud had a high level of trichloroethanol in her body that “would be within the range of concentrations reported in adult fatalities.”

Trichloroethanol is a metabolite of chloral hydrate, which was used as a sleep aid for Michaud. The medical examiner determined her death was accidental.

A fatality inquiry into Michaud’s death was held over seven days in June 2017 and August 2018. The report stemming from that inquiry was released in late July.

“From the evidence before the inquiry, I conclude that Nevaeh’s death was caused by an accumulation of trichloroethanol resulting from receiving a therapeutic dose of chloral hydrate,” Alberta provincial court Judge Elizabeth A. Johnson wrote in her conclusion.

Johnson adopted the following three recommendations from Dr. Michael Rieder, a physician with a PhD in biochemical pharmacology who as called as a witness at the inquiry.

- Chloral hydrate can be used as a short-term measure to assist with sleep in children transitioning to different care situations. The usual dose is in the range of 50 milligrams per kilogram to a maximum dose of 1,000 milligrams. Given that tolerance to the hypnotic effect of chloral hydrate is known to develop within 10 to 14 days, this should be factored into the treatment plan, and consideration should be made to wean or stop chloral hydrate shortly after the transition is accomplished. Chloral hydrate is not an appropriate drug for long[-term] use to assist in sleeping in children.

- Chloral hydrate should be prescribed with this in mind and should be prescribed for a defined period of time. It would be prudent not to have an automatic refill order for chloral hydrate but rather to thoughtfully assess the need and safety of prescribing before refilling a prescription for chloral hydrate.

- Chloral hydrate therapy should be monitored on a regular basis to evaluate dose, efficacy and safety. The therapeutic plan for chloral hydrate should include considerations as to when therapy should be weaned/stopped.

The fatality inquiry heard from 14 witnesses, including Alberta’s chief medical examiner, Children’s Services employees, staff from Mariam’s Footsteps, physicians and a member of the Edmonton Police Service who was asked to review the investigation into Michaud’s death.

The inquiry found Michaud had trouble sleeping and was first prescribed sleep aids in May 2013. Her physician began prescribing chloral hydrate in October 2013 because other medications were not working, the inquiry found. She would receive an initial dose at bedtime and another smaller dose if she woke up. The chloral hydrate dose was calculated based on her weight, according to the inquiry.

- Canadian man dies during Texas Ironman event. His widow wants answers as to why

- ‘Sciatica was gone’: hospital performs robot-assisted spinal surgery in Canadian first

- Honda’s $15B Ontario EV plant marks ‘historic day,’ Trudeau says

- Several baby products have been recalled by Health Canada. Here’s the list

Beyond having trouble sleeping, the inquiry found she “was a child with significant physical and cognitive challenges.”

The inquiry found Michaud received her “regular 7 p.m. dose of chloral hydrate at 6:30” the night before her death. She fell asleep but woke up shortly after midnight, when she was given a second dose of the drug, the inquiry stated.

She woke up again 4:15 a.m. but fell back asleep shortly after 6 a.m., according to the inquiry. At 8 a.m. when a new shift came on, Michaud was breathing louder than usual, the report stated. At around 8:20 a.m., a staff member had prepared milk for Michaud. The girl did not respond but was still breathing loudly, the report read.

When the staff member checked on the girl “some time” later, she was no longer breathing, the inquiry report said. CPR was reportedly performed on the girl while a staff member called 911. The girl was taken to hospital, but despite efforts to revive Michaud, she was pronounced dead, the report said.

Johnson suggested the recommendations be directed to the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta (CPSA) and brought to the attention of the Canadian Paediatric Society.

In a response dated Aug. 30, the CPSA wrote a letter to the justice and solicitor general’s fatality inquiry co-ordinator accepting the recommendations in principle. However, the college pointed out that it is not its role to develop clinical practice recommendations.

The college said it will inform its members about the case and encourage them to also consult other peer-reviewed literature “to ensure that they are prescribing for pediatric insomnia in accordance with the most recent evidence.”

The purpose of a fatality inquiry is not to assign blame but to identify the circumstances around a person’s death and to make recommendations to prevent similar deaths from happening.

Comments