An Alberta deer farm recorded Canada’s third case of a so-called “zombie deer disease” last month.

While the chronic wasting disease (CWD) outbreak was contained — and no infected meat entered the Canadian food supply — experts say more needs to be done to stop the infectious disease from spreading.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency confirmed on July 26 a case of the infectious disease in a herd of white-tailed deer.

This is the third case of CWD in Canada for 2019. The two other infections were also identified in Alberta — on Feb. 28 in elk and on June 21 in white-tailed deer.

The incurable neurological disease spreads between animals through bodily fluids and gradually eats holes in the animals’ brains. CWD was dubbed “zombie deer disease” partly because of the symptoms it causes in animals, including stumbling, lack of coordination, drooling, aggression and a lack of fear of people.

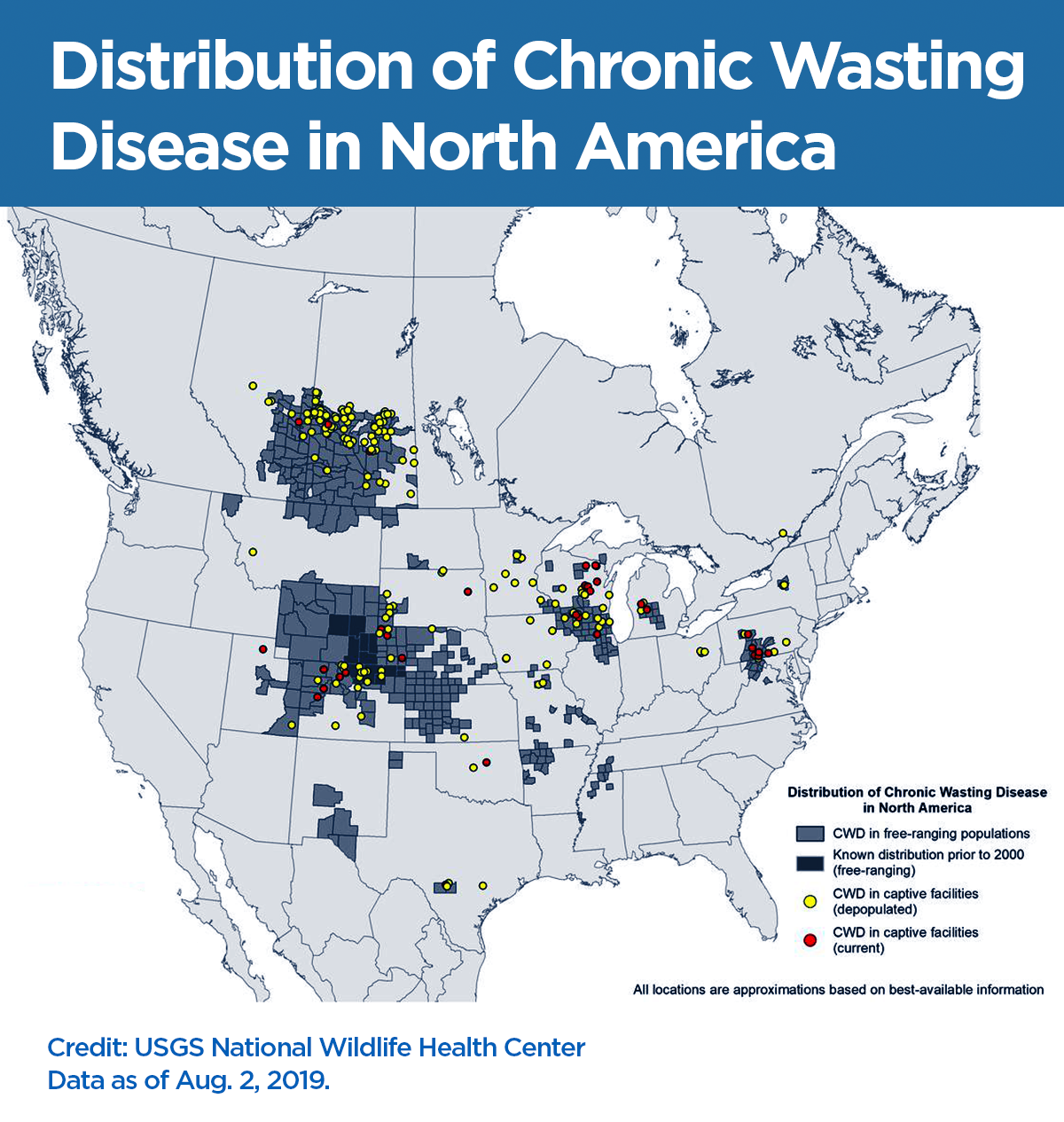

Over the past few years, CWD has made its way through elk and deer populations in multiple Canadian provinces.

In the U.S., it has been confirmed in 26 states.

While there is no direct scientific evidence to suggest that CWD can be transmitted to humans, the CFIA says the consumption of meat from contaminated animals should be avoided.

But, according to some advocates and researchers, the disease is adapting and warrants more scrutiny and preventative action.

WATCH: ‘Zombie Deer Disease’ causing stir in U.S. midwest

Darrel Rowledge, the director of Alliance for Public Wildlife, said CWD shouldn’t be discounted as an animal-only problem.

Rowledge said that while it’s difficult for a disease to jump from one species to another, signs the disease is evolving are alarming.

“Just because it hasn’t happened yet, doesn’t mean that it hasn’t happened,” he said. “A majority of our diseases have evolved to a place where they can infect people.

“We think about 70 per cent of our diseases have come to us from other animals.”

Rowledge is one of 30 experts from across North America who sent a letter to the federal government in June, urging the prime minister to “mandate, fund and undertake” a number of “emergency directives” to contain the disease, prevent human exposure and expand its surveillance program of prion diseases.

The letter — signed by scientists, hunting groups and Indigenous advocates — labelled the spread of CWD an epidemic.

“While no human cases of CWD have been confirmed, scientists note that while low, the risk is not zero — and it is evolving,” the letter reads.

“Thousands of CWD-infected animals are being consumed by hunters and their families across North America every year. Even a single transfer to a person — proving that humans are susceptible — would bring catastrophic consequences with limited options.”

Mad cow — lessons learned?

Rowledge and the other experts used mad cow as an example of what can happen when diseases evolve.

Initially, mad cow (BSE, or bovine spongiform encephalopathy), was never considered to be transmissible between cows, let alone humans through meat consumption. The disease gradually developed and ended in outbreaks in the U.K. and human deaths.

CWD is caused by abnormal proteins called prions, which puts it in the same family as mad cow disease.

“BSE was never contagious, even between cows. CWD is highly contagious between living animals,” Rowledge said.

“They’re spewing out copious amounts of this infectious prion in saliva, feces and urine. Very quickly in a population, especially in captivity, you can get very high rates of infection prevalence in a herd.

“So the predictions about this, when we say things like ‘dire,’ when you look at what it could mean for a wildlife population, it’s worst-case scenario.”

The first Canadian case of the disease was detected on a Saskatchewan elk farm in 1996. Since then, it has been routinely found there and in Alberta.

Most notably, an outbreak at a farm in Quebec last year saw thousands of deer destroyed after nearly a dozen were found to be infected. But the herd wasn’t destroyed completely, and meat from the farm was released for human consumption.

That’s against standards set by the World Health Organization, but not against CFIA policy.

David N. Fisman, the head of epidemiology at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto, said concerns CWD could develop and be transmitted are “legitimate” but aren’t totally panic-worthy yet.

Fisman pointed to research where the disease was transferred to other animals like primates and raccoons.

“People have managed to infect primates with this, but that was done by inoculating it into the brain of another creature and saying, ‘Oh look, we can infect it,’” he said.

He said mad cow should be seen as a “cautionary tale.”

“You can’t say there’s no risk, but this is something that’s been here for a while. It’s known to be in Alberta, it’s known to be in wild populations. Now you have this jumping over into farmed populations that are being raised for consumption,” he said.

“Hopefully folks learned from the from the BSE crisis that you shouldn’t feed animal brains to other animals because that’s how you get about that situation.”

What is Canada doing?

CWD is considered a “reportable disease” under the Health of Animals Act, which means all suspected cases must be immediately reported to the CFIA.

Testing is done on farms in several provinces where deer are slaughtered. Some provinces also offer testing on meat for hunters.

However, “a negative result does not guarantee that an individual animal is not infected,” according to the CFIA.

Since there is no known treatment for the infection, or vaccine for prevention, animals that contract the disease are killed.

The CFIA has established national standards to mitigate the risk of disease and infection in farmed animal herds.

“Animals and products from animals known to be infected with CWD are prohibited from entering Canada’s food supply,” the CFIA said in a statement. “Animals over 12 months of age that pass ante and post mortem inspection are tested for CWD and only animals that are negative on the test are released for human consumption.”

As laid out by Rowledge and his peers in the June letter, there is concern these measures aren’t enough.

He said “flawed public policy” is at the root. It’s why he and fellow advocates wrote the letter.

“Public policy is about asking questions of ‘what if?’ So what if CWD were to transfer to people, what would be the consequences?” he said.

“The notion that there is insufficient proof that CWD will transfer to humans is deceptive and irresponsible, just like BSE… With the BSE inquiry, one of its key lessons was that they said that they should not have been waiting for a person to die.”

Comments