Naturally, our warmer weather means more activity and time outdoors. That can not only be said for people and pets, but for wildlife and insects as well, according to Hamilton Public Health.

Despite a relatively low number of positive tests for common dangerous outdoor afflictions, like West Nile virus and Lyme disease, the city is still suffering from an outbreak of rabies.

That outbreak is largely due to a spike in 2016 numbers which saw the city identify 126 raccoons and 76 skunks with rabies. 2017 was better with numbers dropping to just 45 raccoons and 19 skunks testing positive.

READ MORE: City of Hamilton confirms first case of rabies in two years came from a rabid bat

The city says the positive numbers of rabid animals is down yearly from 2016, but rabies is still circulating among wildlife in the city. Public Health says industry standards require the city to be free of positive testing wildlife for 2 years in order to declare the outbreak over. That has yet to happen.

Jane Murrell, a public health inspector with the city of Hamilton, says human contact typically comes in the way of a passerby discovering an injured, seemingly abandoned or dead animal in the wild.

“It’s when they interact with that wildlife when they want to help it,” said Murrell, “What our issue is, is with the raccoons and with skunks, people have picked them up, put them in their car and taken home for rehab.”

Murrell says they’ve dealt with cases in which people have picked up baby raccoons, put them in a box and taken them home, assuming they were abandoned.

“So humans have put them in the box, then left them in the box, and then children come up and want to play with them because baby raccoons are cute.”

Murrell says wildlife typically leave their young for long periods of time on purpose to wean them away from their mother. It’s when this happens, and a person believes babies have been abandoned that a dangerous situation can occur, particularly if an animal parent spots it.

“They will act differently in that case, doesn’t mean their rabid, they’re just protecting their young.”

The lesson, Murrell says, is don’t interact with wildlife or animals you don’t know. Even some cats and dogs.

“The public is actually more likely to pet or pick up a stray cat as opposed to a skunk, but stray cats are no different than wildlife,” Murrell says. “They’re not vaccinated and we have no idea what interaction they’re having with other wildlife.”

READ MORE: City of Hamilton urging residents to leave wildlife alone

- As Loblaw boycott begins, what to know about all the company’s brands

- Poilievre booted from House of Commons after calling Trudeau a ‘wacko’

- $34B Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project opens after years of construction

- N.S. man stuck abroad due to lack of available hospital beds ‘in our own province’

In recent years, Hamilton Animal Services have used a campaign, referring to strays and feral as “community cats,” to educate residents on the estimated 100,000 that are unowned and roaming Hamilton neighbourhoods.

So far, only two cats have tested positive for rabies in the city since 2016, according to Murrell.

Although wild animals have virus potential, insects pose a risk as well.

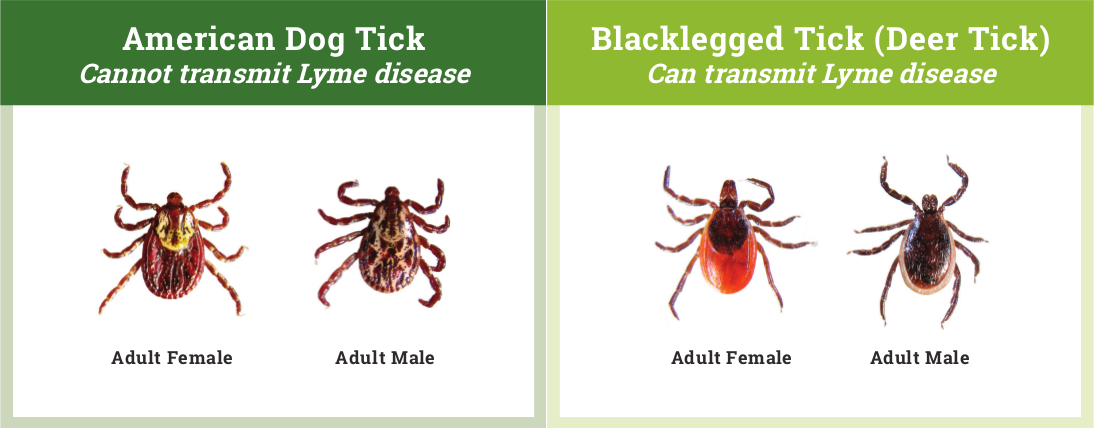

Two of the most concerning are mosquitoes and ticks which are still producing positive tests for West Nile virus and Lyme disease since 2015.

Recent tests show positive news on the Lyme disease front with no positive test from Black Legged Ticks so far in 2019. In 2017, the city discovered eight Lyme-infected ticks from 92 submissions. The number decreased in 2018 with just five positive results.

WATCH: Hamilton Public Health Inspector Jane Murrell with an update on the city’s viral insect population.

Ninh Tran, Hamilton’s associate medical officer of health, says Lyme disease has become a concern in the city in the past two years.

“It’s been historically in other jurisdictions, like eastern Ontario, and Hamilton wasn’t considered a risk area until last year,” said Tran.

Tran says both Lyme disease and West Nile virus are bacterial infections which cause rashes, fever, tiredness, and headaches.

In the case of Lyme disease, he says if untreated, symptoms can progress into serious joint afflictions like arthritis.

“If it’s not recognized early, and untreated, people can get long-term effects like chronic joint pain and even arthritis,” said Tran.

Meanwhile, Tran says West Nile Virus, although a concern, is less likely to pose a problem in most humans.

“Worst case scenario, it can affect the nervous system in the brain and bring on meningitis,” Tran said. “But four-out-of-five people generally don’t get any symptoms at all.”

In regards to treatments for animal and insect bites, Hamilton Public Health suggests a bite from a wild animal should be washed with soap and water followed by a visit to a doctor.

READ MORE: Hamilton Harbour contaminated by near-record dumping of partially treated sewage

A mosquito bite should be washed with soap and water and swelling and itching treated with antihistamines, honey, corticosteroid cream, aloe, or basil. Should a person develop a fever, headache, or body aches, see a doctor.

A tick attached to the skin should be removed as soon as possible with tweezers, carefully pulling it straight up. Do not squeeze it, as that can release more bacteria. Clean the area with soap and water. Do not burn or use chemicals and liquids to remove as that could cause the tick to regurgitate bacteria into your system.

The city of Hamilton also suggests you save the tick for testing by dropping it in a clear jar, a screw-top bottle or zip-lock bag. If possible, keep the tick alive, and pick up a testing kit from municipal service centres or the Public Health offices.

WATCH: Raccoons rounded up in Toronto amid possible viral outbreak

Comments