The four teenagers were relieved to see the police car, at least at first.

It was the winter of 1982, and a road trip to Montreal had gone sideways when their Volkswagen Beetle broke down on the side of Highway 401 in a snowstorm.

They felt a bit out of their depth with the situation.

“We had no idea what was going on,” Mark remembers. “I remember that we were a little afraid in the sense that, ‘Is the car going to be OK? Are we going to make it all the way to Montreal? Are we even going to get any further in the car?'”.

So the flashing lights behind them were a welcome sight.

“Actually, we were quite happy when the police officer pulled up because we thought, ‘Great — this guy’s going to get us a tow truck or get us some help here.'”

But then the officer noticed the rolling papers in the front seat, and that led to him finding the two joints in the cigarette pack in the front passenger seat visor and that led to him arresting Mark, who happened to be sitting in the seat, for possession of marijuana. He had just turned 18.

“It wasn’t mine — it was one of my friends’. I hadn’t been sitting in that seat when we started off. I couldn’t name names because that wouldn’t be very cool at that time of our lives,” Mark says.

A court date in Oshawa followed.

“I was happy because I knew my parents wouldn’t have to be involved. I could also sign myself out of school. I signed myself out of high school and went to this court appearance,” he explains.

It ended in a conditional discharge, a sentence sometimes used for minor offences where the accused isn’t treated as convicted if he fulfils some condition or displays good behaviour going forward. (Conditional discharge records after 1992 are sealed automatically, but those before that date are only sealed if the person requests it.)

“I didn’t need to do anything. I just needed to stay out of trouble for a year,” Mark said.

And that is where things rested for 37 long years, until a few weeks ago at the Peace Bridge border crossing on the Niagara River. Mark, now in his mid-50s, had crossed the U.S. border many times, but this time, the border guard took longer than usual.

“He was looking at our passports and he wasn’t asking us any other questions. He just said: ‘You need to go in — there’s a problem with your documentation,’” Mark says.

“I thought: That’s weird, We’ve got 10-year passports; they’re good for a long time still.”

Mark faced a short interrogation.

“He said to me ‘Have you ever been arrested?‘ I said no. He said: ‘Are you sure?’ ‘No, I’ve never been arrested.’ ‘You can’t lie to me.’ ‘I’m not lying to you.’ He said: ‘Have you ever been arrested?’” Mark explains.

“I never even thought of that time when I was 18 years old, 37 years ago. Never even crossed my mind until he started pushing it and pushing it.

“He said: ‘You’ve been denied entry. You’re a criminal for cannabis possession.’ I said: ‘You’ve got to be kidding me.’”

Mark found himself photographed, fingerprinted and banned from the United States for life.

“That’s completely humiliating. I felt like a criminal — like I’d murdered somebody or something,” he says.

Decades-old convictions unearthed as record systems improve

Get daily National news

Data connections between Canadian and U.S. border officials are improving, and paper records that have been slumbering for many years in archives are being digitized, lawyers explain. As a result, long-forgotten Canadian marijuana convictions from many decades ago are popping up at the U.S. border.

“More people who, historically, had been able to cross are finding themselves where they’re not able to cross because this information became available to immigration on the U.S. side,” says Toronto-based immigration lawyer Heather Segal. “They didn’t even know, necessarily, that they were inadmissible because they’ve been crossing for years.”

About 400,000 Canadians have prohibition-era records for simple possession of marijuana.

“That’s why a lot of this stuff pops up — because of digitization of old records,” says Blaine, Wash., immigration lawyer Len Saunders.

“People say: ‘But I’ve been travelling back and forth for 40 years!’ It doesn’t matter — you just got lucky.”

Mark, who didn’t want his full name used for professional reasons, is the third known case of a Canadian being banned from the U.S. for a cannabis-related reason since legalization.

The first was a man who admitted to U.S. border officials at the Vancouver airport that he was going to look at a Las Vegas cannabis production facility he’d invested in. (Confusingly, it’s legal at the state level but not federally.)

The second was Bev Camp, a 73-year-old man from London, Ont., whose 1976 conviction for possession of marijuana came up on a border official’s computer. (He had also been crossing for years.)

Before legalization, it was quite common for Canadians who admitted to cannabis use at the border to be banned for life. Saunders says a large part of his legal practice concerns Canadians’ marijuana issues at the border.

U.S. federal law bans “abusers” of drugs banned in the United States, including marijuana, from entering the country. “Abuse” refers to any level of use, regardless of legality where it took place.

However, there is no known case of a Canadian being banned from the U.S. for legal consumption in Canada since last October or for working in the legal industry here.

“I haven’t seen anything like that, personally,” Segal says. “I imagine that would have made the press already because someone like that would be important.”

But it’s hard to know for sure. (Global News asked U.S. Customs and Border Protection for statistics on how many Canadians have been banned from the U.S. for cannabis-related reasons, and it refused to say.)

“Not everybody wants to talk to the media,” Segal says. “People just want to move on and make the application for waivers. What we hear about may not be representative of what’s actually going on — there may be more cases, but we don’t know.”

Last October, just before legalization, CBP said it would not ban Canadians working in the legal Canadian cannabis industry. That was a major shift from the month before when the agency said that “working in or facilitating the proliferation of the legal marijuana industry in U.S. states where it is deemed legal or Canada may affect admissibility to the U.S.”

Waivers to cross the border are intrusive and expensive

In principle, people banned from the U.S. can ask for a waiver to be allowed in. But the process is expensive and complicated, and the documents move sluggishly through an overloaded office in Virginia, immigration lawyers say.

“You need two letters of reference from reputable members of the community, you need a letter of remorse saying you’re remorseful for your past indiscretion, you need proof of employment or retirement,” Saunders says. “I have no idea why they care if you work or not.”

At least some effort to appear repentant is necessary, Segal says.

“In my experience, you have to say that what you did was wrong. If you don’t recognize your own wrongdoing, there’s a problem,” she explains.

Since the process can take up to a year, and at first, waivers are only given out for a year, the process of getting the renewal underway has to start when the first one arrives.

“I have a list of clients and I call them a year in advance, tell them their waiver expires in a year, to get a new criminal record check and call me back then, and we just go through the list,” Saunders says. “New letters of reference, new proof of employment or retirement. We need, instead of a letter of remorse, a letter of appreciation and we have to go through the whole thing all over again.”

“I tell clients: The bad news is you have to do renewals. The good news is that these are clients for life. They never go away. These are files I never close. I’ve built up a huge repeat business of waiver clients.”

Between legal bills and government fees on both sides of the border, the whole thing costs around $3,400 for a first-time application. (Saunders charges less for handling a client’s renewal.)

The process continues until the person either dies or loses interest in going to the United States.

“You need them forever,” Segal says. “You never get rid of needing a waiver. “

The Virginia office makes itself hard to contact, Saunders says.

“There’s no phone number. There’s an email address, but it’s spotty whether they reply. It’s an agency of CBP that is unreachable by all practical means.”

Mark started gathering documents for a waiver application but has now made his peace with never crossing the border.

“If that’s my only option here then I’m just not going to travel into the United States again,” he says.

“I would do it without any problem. I would think it was a joke the entire time I was writing it but I could do that if that was the requirement. I would not like to have to get a letter from my employer. I’ve been working there for over 20 years and I don’t think it’s any of their business.”

Convicted impaired drivers and drivers who have killed people can freely cross the border

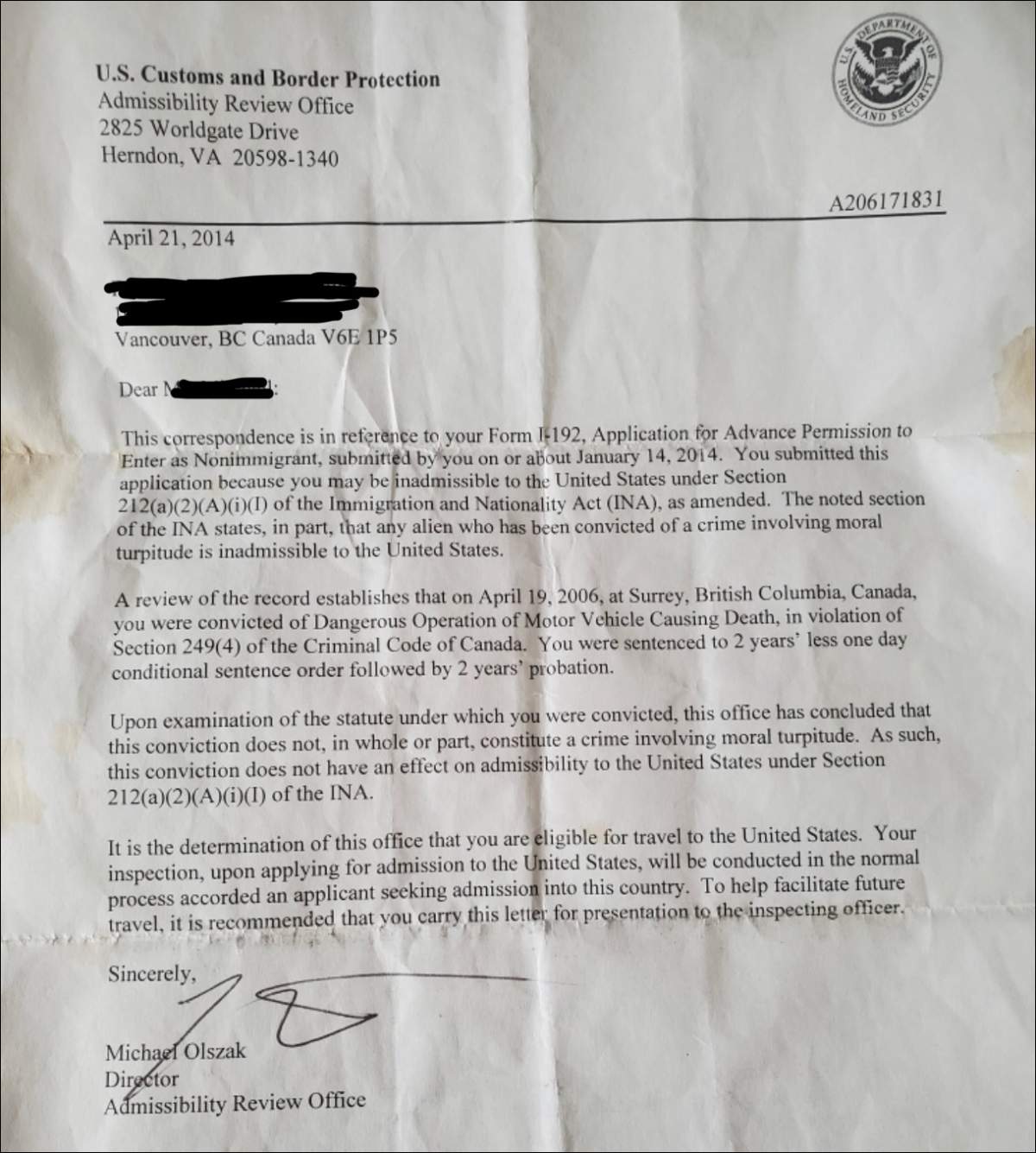

People with far worse crimes than marijuana possession have no issue entering the United States. Canadians with records for several impaired driving offences cross freely back and forth, and Saunders says he has three Canadian clients with convictions for dangerous operation of a motor vehicle causing death who are free to cross the border any time they like.

“They let in people with DUIs, dangerous operation of a motor vehicle causing death, but because a controlled substance violation is a crime involving moral turpitude, you’re barred for life for something you did back in your 20s, which is now legal. It doesn’t make sense,” Saunders explains.

“I have clients who have multiple DUIs, and they don’t need waivers. But the old cannabis stuff, it’s like you’re some horrible person.”

Mark recalls his experience at the border.

“The border agent even said: ‘If you had been charged with driving while impaired or theft or something like that, you’d go in,'” Mark says. “‘But with cannabis, definitely not.’

“That’s the kind of person you don’t want in your country because they could harm someone. They could get behind the wheel while they’re drunk and hurt someone else. To me, that’s a criminal. I’m not a criminal.”

Global News reached out to CBP’s Buffalo, N.Y., office for comment.

“Admissibility decisions and any follow-on actions are made by CBP officers on a case-by-case basis taking into account the entirety of the situation and all available information,” wrote a CBP spokesperson.

“Aliens must overcome all grounds of inadmissibility, including admissions of past violations of controlled substance law. Possession and/or admission to the use of marijuana by an alien may result in the refusal of admission.”

The spokesperson did not directly answer a question about how bans of this kind protect public safety in the United States.

“The most interesting thing about this, for me, is that over 40 states in the United States have legalized cannabis,” Segal says. “Cannabis is traded on the New York Stock Exchange. It’s a huge moneymaker. It’s a huge source of resources for states and, federally, it’s illegal.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.