Avalanches can happen at any time of year — given the right conditions — but December to April is when most tend to occur.

Avalanches can be triggered one of two ways: natural causes, like strong winds or a dump of snow, or humans activity, like skiing or snowmobiling.

The results can differ widely, avalanches can be relatively harmless or destroy a village — they can move at 15 km/h or 130 km/h in a matter of seconds.

There are an average of 12 avalanche fatalities per year across the country, according to Avalanche Canada, and most victims are snowmobilers.

READ MORE: Timeline of Canada’s deadliest avalanches

Avalanche Types

Avalanches can be simply defined as a mass of snow moving quickly down a mountain but in reality, they’re much more complex.

Here is a break down of each type of avalanche, how they form and their triggers:

Loose Snow

Loose snow avalanches, also known as sluffs, are usually small and pose a very low safety risk.

They are triggered below a disturbance — like a skier or snowmobiler — instead of above, like slab avalanches.

Sluffs can be dangerous to ice climbers, who may end up pulled downwards by a loose snow avalanche.

Dry VS wet snow

Get daily National news

Dry and wet snow avalanches are completely different beasts.

They differ in how they form, fracture and are triggered. They even move down the slope differently.

Wet avalanches are caused by prolonged melting and rain, therefore making them more common in the springtime.

These avalanches happen because the snowpack is weakened when water fills gaps in the snowpack and eventually causes it to slide.

The slide usually contains a heavy mixture of large icy and slushy chunks of snow and are the slowest of all avalanches, sometimes moving as slow as 20 km/h.

Because these avalanches are so slow, they result in fewer fatalities — unlike dry snow avalanches which are the leading cause of avalanche fatalities.

Dry snow avalanches are usually human-triggered but can also occur from an overload of new or windblown snow.

Because these avalanches take place when temperatures are below freezing and the snow is dry, they can look like slabs or as loose snow.

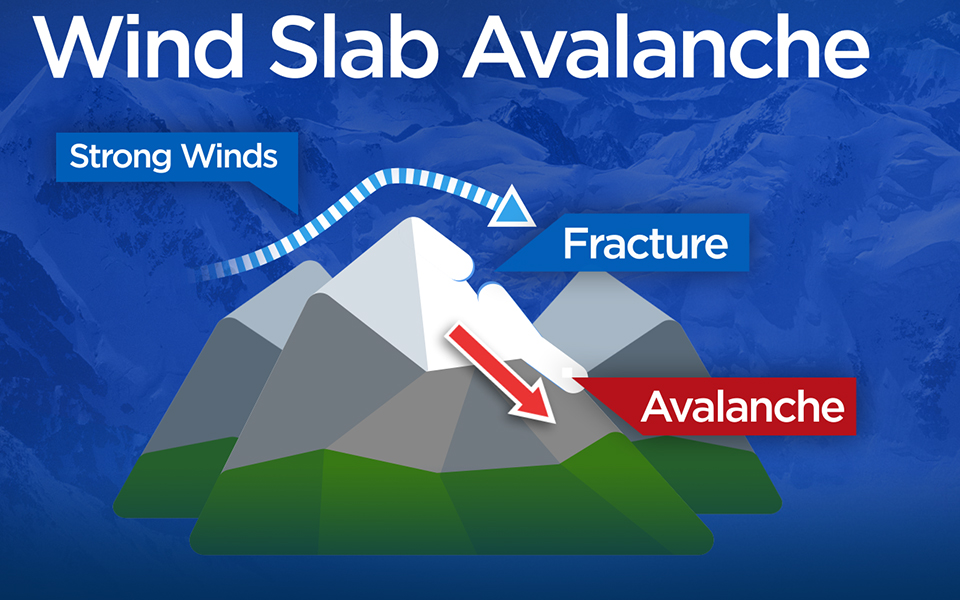

Wind Slab

A slab is a section of stronger snow that lies over weaker snow and can be thought of as a pane of glass over potato chips.

Wind can influence a slab by packing together the weaker snow and causing “pillows,” which are round, smooth mounds of snow.

These “pillows” are most commonly created on the lee side slopes and cross‐winded terrain.

When a wind slab breaks loose, it can be dangerous and potentially fatal to anyone below.

Soft VS hard slab

Soft slabs are light and made up of new snow while hard slabs are stiff, usually made up of older, solid layers of snow.

The latter is more likely to cause a large and potentially deadly avalanche because the fracture usually occurs well above the trigger, which makes it difficult to escape.

The good news is, the stiffer the slab, the harder it is to trigger an avalanche but when it does happen, it consists of hard chunks of snow.

Soft slabs are less dense and cause avalanches that are soft and powdery, sometimes breaking near your feet, which make them less of a safety risk.

Deep slab

Deep slabs of snow start building early in the season and can be dormant for weeks.

Typically problems arise when there’s a slab of old, weak snow at the bottom, hardened snow in the middle and new snow on top.

When the weaker snow loses its bond near the ground, the avalanche happens.

If the deep slab is well bonded and undisturbed, it requires a heavy trigger — like another avalanche or snowmobiler.

However, when the slab is weakened from weather changes, an avalanche can be triggered easily and without warning.

These avalanches can be unpredictable, dangerous and deadly.

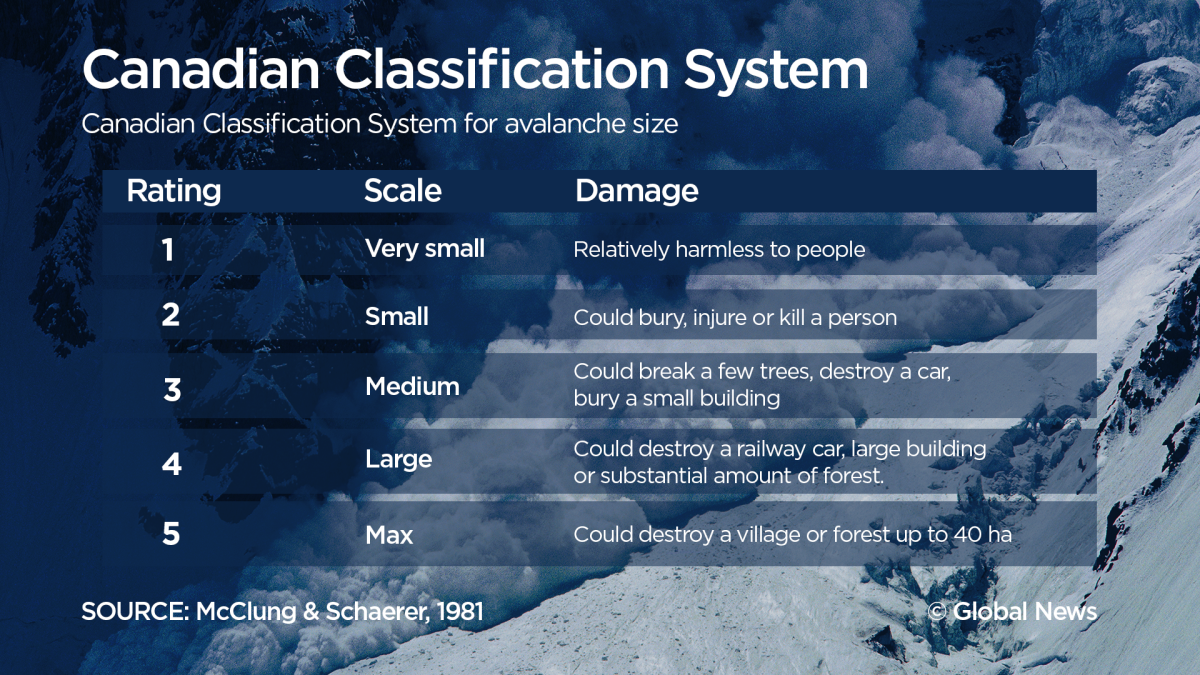

Avalanche Sizes

The avalanche size classification scheme used in Canada ranks avalanches on a scale of one to five.

Size five avalanches are very rare in Canada, whereas size one avalanches are occurring frequently.

WATCH: Dramatic video captures California rescue of man buried in avalanche

Avalanche Safety

When heading into the mountains, officials advise checking the avalanche forecast and continuously evaluating avalanche conditions.

They also recommend travelling in pairs or groups and with rescue equipment, as well as an avalanche rescue beacon.

Avalanche Canada‘s list of essential gear includes an avalanche transceiver, 320 cm long probe, shovel and a transceiver interference.

If heading into the backcountry, they also recommend carrying avalanche airbag packs and, because cell service may not be avaialble, an emergency communication device like a satellite messenger or satellite phone.

The National Geographic reports that 93 per cent of avalanche victims survive if dug out within 15 minutes.

Unfortunately, survival rates drop quickly after that, with only 20 to 30 per cent of victims found alive after 45 minutes and a very small number of people survive if buried for two hours.

Officials say if you are caught in an avalanche, try to get off the slab. If you are unable to escape, grab onto a tree and if you’re swept away in the snow, start swimming towards the surface.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.