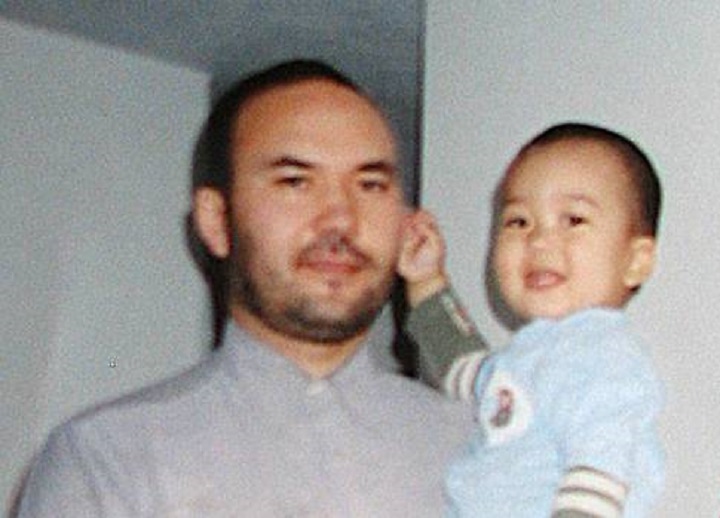

When they were little, Kamila Telendibaeva’s sons used to ask her the same question every day: “When is my dad going to come back?”

Three of her four boys are teenagers now, and they don’t ask about their dad much anymore — except when they see the news. They get worried when they read headlines like “China is holding a million Muslim Uighurs in secretive internment camps.”

Their dad, Huseyin Celil, is a Uighur activist who became a Canadian citizen in 2005. He was arrested during a family trip to Uzbekistan in 2006 and handed over to the Chinese in 2007.

Celil was convicted on vague terrorism charges in a trial that Canada denounced. He was sentenced to life in a Chinese prison, where he’s been languishing for nearly 13 years without access to a lawyer. China has refused to acknowledge his Canadian citizenship or grant him access to consular services since his arrest.

Kamila and Amnesty International Canada, who handles his case, say there has been no change on either front.

Canada and human rights groups denounced Celil’s secretive trial as unjust, but China maintains that Celil is a separatist and a terrorist, without citing any evidence.

Kamila says she’s glad to see Canada working hard to free the Canadians who were recently detained in China, amid an escalating dispute over the arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver last month. However, she worries Canada has given up on securing Celil’s release as well, and that he’ll turn 50 in a jail cell on March 1.

“I need the Canadian government to do more,” Kamila told Global News from her home in Burlington, Ont.

She knows Canada has tried hard to get Celil back. Former prime minister Stephen Harper raised his case multiple times with China’s prime minister. But Kamila says Prime Minister Justin Trudeau hasn’t done enough to press the issue with China during his tenure.

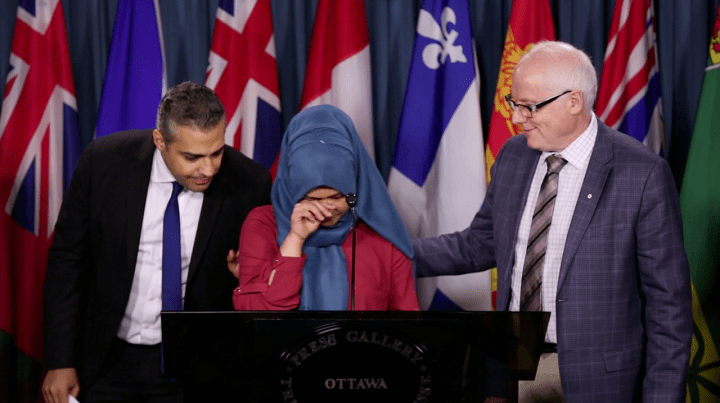

WATCH BELOW: Kamila Telendibaeva urges Canada to help her husband in 2006

“We are deeply concerned by the detention of Mr. Huseyincan Celil and we continue to raise this case at senior levels,” a spokesperson for Global Affairs Canada told Global News in a statement. The spokesperson used Celil’s extended first name.

“To protect our efforts and the privacy of the individual concerned, we cannot release further details on this case.”

The Chinese consulate did not respond to a Global News request for comment.

From Uighur activist to Canadian father

Huseyin Celil’s long history with Chinese authorities began with a call to prayer.

It was 1994, and the 25-year-old imam used a megaphone to amplify the Muslim call to prayer in his home province of Xinjiang in western China. Celil’s action ran afoul of the Chinese Communist Party’s law against public displays of religion. He was thrown in prison for 48 days and upon his release, he quickly fled the country to neighbouring Uzbekistan. That’s where he met and married Kamila, who would later move with him to Turkey to start a family.

“He was very calm and humble, and an outspoken person,” Kamila said. “For his people, he would always stand up.”

Celil and his family arrived in Canada in 2001, after the United Nations granted him status as a political refugee. They settled in Burlington, Ont., and Celil became a Canadian citizen in November 2005.

He was using his Canadian passport when he, Kamila and their three boys flew to Uzbekistan to visit Kamila’s family in March 2006. The country is close to China’s Xinjiang region, where most of the world’s Uighurs live.

Kamila last saw Celil at her family’s house in Tashkent, where everyone sat around the table and enjoyed a meal together that morning.

Get breaking National news

Afterward, Celil went out to fetch his passport from the Uzbek authorities. He never came home. The Uzbeks had arrested him on behalf of the Chinese, who charged him with terrorism.

Amnesty International Canada took up Celil’s case after Kamila returned home in mid-2006. Together, Kamila and Amnesty representatives urged the Canadian government to call for Celil’s release. Amnesty members in Burlington also chipped in to help Kamila handle the new task of raising four boys on her own.

“I don’t think any of us can begin to image the toll that takes on a family,” said Alex Neve, secretary general of Amnesty International Canada.

Uighur crackdown in China

Celil was targeted as part of an ongoing campaign by the Chinese government to oppress and persecute its Uighur minority, according to Amnesty International Canada.

“This is a man who cared deeply about his people,” Neve told Global News.

“He, too, deserves our concern as Canadians, and deserves every measure possible from the Canadian government to win his freedom.”

The Uighur people are an ethnic group of Turkic Muslims living mostly in Xinjiang, an autonomous region in western China. Some among them want to establish their own nation called East Turkestan, although China has condemned any movements dedicated to that goal. One such group, the Eastern Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), was added to the UN’s list of terror groups in 2002.

A Human Rights Watch report says the Chinese have intensified their persecution of the Uighurs since 2014, under the government’s “Strike Hard Campaign Against Violent Terrorism.” Chinese officials have banned many religious practices, arrested potential pro-Turkestan supporters and encouraged outsiders from other parts of the country to move to Xinjiang in order to dilute Uighur culture, the report suggests.

China has also tried to compel Uighurs living abroad to return to Xinjiang, Human Rights Watch says.

China has said Xinjiang faces a serious threat from Islamist militants and separatists who plot attacks and stir up tension between the mostly Muslim Uighur minority and the ethnic Han Chinese majority.

The violence has been going on for many years. In 2009, for instance, more than 140 people were killed when police clashed with Uighur protesters in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang. The Uighurs had been protesting after the deaths of two of their own in a factory in southern China.

A market bombing in Urumqi in 2014 has also been attributed to Uighur terrorists.

Last year, the government responded to the perceived threat by cracking down on the Uighurs in Xinjiang, forcing approximately 1 million of them into detention camps. China has denied the existence of any detention camps, contradicting stories of former prisoners and several reports from human rights’ groups.

WATCH BELOW: China shows off ‘education centres’ despite global concern

Beijing has also denied that such camps are for “political education,” saying they are instead meant to provide vocational training and discourage extremism. It rejected a call from the United Nations last August to immediately release the captive Uighurs.

China has also been accused of using its “Pair Up and Become Family” program to place Han Chinese “relatives” in the homes of Uighur families in order to spy on them.

Many Uighurs claim their new “relatives” are watching for and reporting any separatist or overtly religious behaviour.

- Khamenei’s death met with ‘jubilation’ among Iranian-Canadians: Liberal MP

- ‘At first I cried’: How Iranian Canadians are reacting to the U.S. strikes in Iran

- Iran begins search for new leader; U.S. military says 3 service members killed

- Queen’s University students stranded in Doha after Iran attack shuts down airspace

Authorities in Xinjiang celebrated the program with “Becoming Family Week” in December 2017. Government reports on the program gushed about warm “family reunions” as public servants and Uighurs shared meals, parenting duties and even beds.

Canada accused China at the UN last November of violating the Uighurs’ human rights, and expressed concern about “credible reports of the mass detention, repression and surveillance of Uighurs and other Muslims in Xinjiang.” Canada was among several countries, including the United States, to rebuke China after reviewing its human rights record at the UN.

Tamara Mawhinney, Canada’s deputy permanent representative to the UN, urged China to “release Uighurs and other Muslims who have been detained arbitrarily and without due process for their ethnicity or religion.”

Neve believes Celil is still in a prison in Xinjiang, and not in one of the Uighur detention camps.

“His situation continues to be very pressing and very urgent,” Neve said.

Kamila worries Celil’s family has been swept up in the Uighur crackdown.

13 years alone

Kamila says it’s been “very challenging” as the only parent to four sons. “I cannot handle my tears — it’s so difficult,” she said. “I don’t know how I’ve managed.”

Her oldest son, who is 19, requires additional care. Abdul, 15, Badrudin, 14, and Zubeyir, 12, are now old enough to help around the house, but they can also be a challenge at times.

The three older boys only have faint memories of their father. However, he’s only a story for Zubeyir, who was born six months after his father’s arrest.

WATCH BELOW: U.S. to formally seek extradition of Huawei CFO

Kamila received mixed news about Celil in early 2017. Chinese officials announced at the time that Celil’s life sentence had been reduced to 20 more years in prison, because he had delivered a confession and undergone re-education training.

“I don’t know if in 20 years he’s going to be alive,” she said. She’s also not sure she trusts that her husband will be released by Chinese authorities when his prison term ends.

But she still holds on to a bit of hope, especially with Canada-China relations at a crucial point.

China detained Michael Kovrig, a Canadian diplomat on leave, and businessman Michael Spavor last month. China also sentenced Canadian Robert Lloyd Schellenberg to death on Jan. 14, following a swift and widely criticized retrial. He had previously been convicted of drug charges.

The Canadian government has vowed to stand its ground against China in the ongoing dispute, and it is calling on allies to support its bid to free the detained Canadians.

“We have never seen this kind of full-court press that is now, very importantly, happening for the three Canadians,” Neve said.

However, Celil is unlikely to win his freedom at the same time as the other detained Canadians, according to Guy Saint-Jacques, Canada’s former ambassador to China. Saint-Jacques, who served as ambassador from 2012 to 2016, said China rejected every one of the Canadian government’s requests to set Celil free — even those from PM Harper.

“They won’t release him until he has served his whole sentence,” Saint-Jacques said.

WATCH BELOW: Guy Saint-Jacques explains detention process for Canadian Michael Kovrig

Kamila says she’s not ready to give up on her husband, even if it takes years to secure his freedom.

“I hope he’s going to be released,” she said. “I hope he’s going to come home and take care of the boys.”

— With files from The Canadian Press and The Associated Press

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.