Canada’s a rich country with a gross domestic product of over $2 trillion and national wealth valued at over $11 trillion.

But just how much of those riches are wrapped up in real estate? A sizable share, it turns out.

Coverage of Canadian real estate on Globalnews.ca:

Statistics Canada released last week its third-quarter report on national wealth, which is the “value of non-financial assets in the Canadian economy.”

Total national wealth hit $11.415 trillion in the third quarter, and at $8.752 trillion, real estate made up a 76-per-cent share of that figure — nearly all but a quarter.

That was the highest that both figures had been, going back to the second quarter of 2007.

This graph shows real estate as a share of national wealth in Canada and the U.S.:

Analysis of data from the U.S. Federal Reserve indicates that this is a higher share of national wealth than real estate takes up in the United States.

But it wasn’t always this way.

Data from both countries shows that real estate as a share of U.S. national wealth was previously 75.3 per cent, compared to 67.6 per cent in Canada.

That started to change with the 2008 recession.

READ MORE: New report says B.C. housing market in midst of recession that could last for 3 years

Real estate as a share of U.S. national wealth started to decline in the late aughts, going from 75.3 per cent in the second quarter of 2007 to 70.5 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2008.

This happened at the same time that real estate as a share of Canadian wealth was growing, reaching 74.3 per cent in the first quarter of 2009, while in the U.S. it was 70.2 per cent at that time.

This chart shows how real estate wealth trended in Canada and the U.S. from 2007 to 2018:

These trends come as Canada has seen real estate grow consistently as a share of national wealth over the past decade. In the U.S., meanwhile, real estate wealth dropped amid the Great Recession and started rebounding around 2012.

Canada’s growth has largely been driven by increases in land value, as the following chart demonstrates:

Canadian land values grew consistently from the first quarter of 2009 up to the first quarter of 2017, going from just over $2 trillion to about $4.2 trillion in that time frame.

Get breaking National news

But then values started to level off, dropping to $4.1 trillion in the third quarter of 2017. Values grew again, but the growth hasn’t been as consistent since then as it had been over the past decade.

The value of residential and non-residential structures has also grown over that time.

WATCH: More sub-$1,000,000 homes listed in Vancouver

BMO senior economist Sal Guatieri wasn’t surprised to see real estate make up such a heavy share of national wealth in Canada.

The share rose amid a “sharp rise in home values” that happened in a few Canadian cities over the decade, particularly Toronto and Vancouver, he told Global News.

He said the amount of real estate wealth could prove to be a concern amid a “sharp, sustained correction in house prices given the wealth effect on spending.”

READ MORE: Falling B.C. real estate market projected to bring national home sales down to nearly 10-year low

Research by Moody’s earlier this year talked of the “wealth effect” — the effect of household wealth on consumer spending.

The credit rating agency looked at U.S. consumption and estimated the wealth effect at 4.5 cents, meaning that for every $1 change in household wealth, consumer spending could change by 4.5 cents.

A pullback in spending attributed to falling home prices could prove to be a drag on GDP growth.

Guatieri, for one, didn’t appear immediately concerned.

“Flat prices aren’t a big deal,” he said.

“It’s only if prices fall sharply that people would likely pull back spending.”

BMO has estimated that Canadian benchmark home prices will grow by less than one per cent next year and two per cent in 2020, dragged by “tougher mortgage rules and higher interest rates so the share should continue to trend modestly lower.”

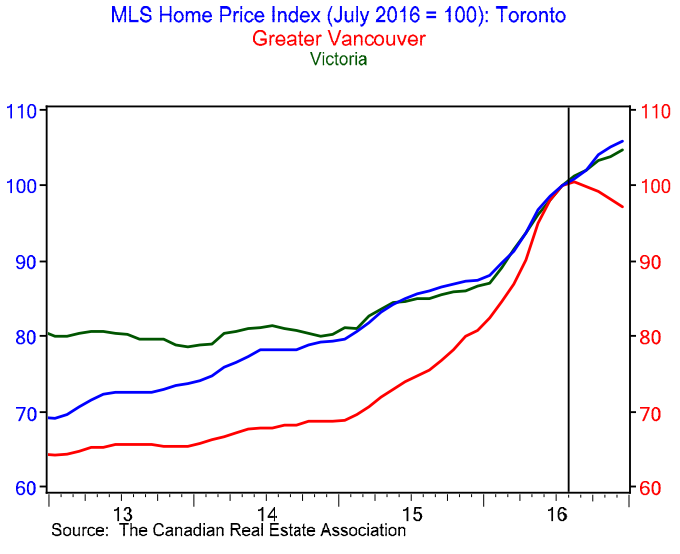

The latest trends also come amid the implementation of measures meant to curb demand in Vancouver and Toronto, which, in recent years, have been Canada’s hottest housing markets.

B.C. has implemented a suite of measures since 2016, bringing in a 15-per-cent property transfer tax on foreign buyers that year that has shown a clear effect on price growth.

The province later introduced several new measures in the 2018 budget, including increasing the reach of the foreign buyers’ tax and implementing a speculation tax that would charge 0.5 per cent on second homes that aren’t rented out for more than six months in a year.

Ontario, meanwhile, introduced in 2017 a series of housing measures, including a 15-per-cent tax on non-resident speculators in the Greater Golden Horseshoe as well as expanded rent controls and the ability for municipalities to level taxes on empty homes.

Toronto home prices have cooled off, too.

WATCH: B.C. mayors call for changes to speculation tax

Guatieri may not be concerned about the growth of real estate wealth, but economists at CIBC feel quite differently about the effects of a housing slowdown on Canada’s economy.

“For Canada, the housing market is more important to the overall economy than at any other time on record,” Benjamin Tal and Royce Mendes wrote.

They noted that residential investment makes up 7.5 per cent of Canada’s economy, which is just off a historic peak.

The authors noted the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) argument that the “worst is now behind us and that housing markets are stabilizing.”

But from their standpoint, “it’s difficult to agree.”

The BoC’s workhorse model says that six quarters can pass before a rate hike can be felt in the economy, they noted.

In this case, however, only five quarters have passed since the first move of this cycle, and “we’re already seeing a slowdown in housing-related indicators,” Tal and Mendes said.

“As a result, we’re not as optimistic as the Bank of Canada for the contribution to GDP growth from housing over the next few years,” they wrote.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.