As part of an in-depth investigation into the city’s ongoing meth crisis, Global News / 680 CJOB journalists Richard Cloutier and Joe Scarpelli were given exclusive behind-the-scenes access to the people on the front lines in the fight against meth. This is the second of a four-part series.

Read the first part of the series: On the front lines of Winnipeg’s Meth Crisis

While much has been made of the meth crisis writ large throughout the city, for some Winnipeggers, it hits much closer to home.

Laurie Chapman’s daughter is a meth addict currently in treatment, something she’s tried before without success. After having to forcibly remove her daughter from her home and have a protection order filed, Chapman told 680 CJOB Tuesday morning that she’s running out of ideas about what she and her family can do to help.

“We miss her. We love her and we want her back, but we can’t have her back the way she was,” said Chapman. “Meth is such a different monster of a drug compared to drugs she’s used in the past.

“It stays in their system for so long. I think they’re saying they have a 17 per cent success rate with meth. I applaud the people at detox, because they’ve tried numerous times.”

Her son, Adam, said concern over his sister’s health and well-being, and the feeling of powerlessness that comes with it, affects every aspect of the family’s lives.

“I can’t enjoy a mouthful of food because I don’t know if she’s eating,” he said. “She’d be walking around with no clothes on downtown in the middle of winter. I’m surprised the elements didn’t get her.”

Laurie Chapman, who said she last saw her daughter about a month ago, agreed.

“It totally envelops your life,” she said, “waiting for the phone call or the knock at your door that they’ve found her dead.”

The Chapmans’ ordeal is familiar story for a listener who wrote in to 680 CJOB to share her experience.

Get breaking National news

“My husband and I are dealing with our 25-year-old daughter who is in the midst of the meth crisis,” said the woman, who asked to remain anonymous. “It’s been with us for years. The way things are right now, there is no way out. For her or for us.

“Whether high on meth or coming off, she’s not of sound mind. She cannot and should not be able to make any decisions on her own.”

The woman said her daughter recently attempted to go to treatment, but came home after a only few days and was back on meth soon after.

But it’s not just families dealing with addicts who struggle.

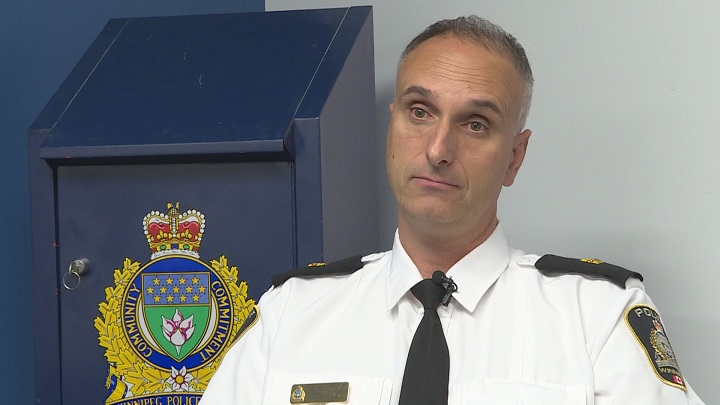

Ask anyone who has had their bike stolen, their garage broken into or their car windows smashed, and it’s likely an addict searching for something to sell that’s behind the property crime, said Max Waddell of the Winnipeg Police Service’s Organized Crime Unit.

That’s when addicts haven’t succumbed to the paranoia that often accompanies being high on meth.

“We’ve had individuals jump off of buildings, individuals throwing pieces of concrete at our police officers, people taping machetes to their arms and asking police to, to take them out.”

And it’s in every corner of the city, he added.

Pharmacist Carey Lai said he’s seen first hand the crime that surrounds meth, including his pharmacy on Leila Avenue being targeted by those looking for their next fix.

“We were about to close, and we had an individual with a ski mask coming in, holding a machete coming in and demanding drugs,” he said.

Dealers or those who are addicted and want to make more steal the ingredients in the pharmacy to make the meth, or they steal other drugs with street value in an effort to sell them to pay for more meth, he said.

Dr. Ginette Poulin, medical director at the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba (AFM), said meth is now the most-reported primary drug of use among people accessing care at AFM facilities, with an increase of over 50 per cent over the last few years. She cites the low cost and easy availability of the drug as being among the main reasons for its local resurgence at the top of the illegal drug market in Manitoba.

“What’s interesting is that we’re seeing products on the illicit market today that are extremely potent and toxic, leading to substantial consequences, such as physical aggression and psychosis,” said Poulin.

“We’re seeing this show up at many doors, not just at the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba, but with our emergency services or police showing up to calls.”

The statistics bear out that statement, with the Manitoba Nurses Union reporting a 1,200 per cent increase in meth-related emergency room visits since 2013, and a long list of recent violent incidents Winnipeg police have had to address.

Poulin says one of the difficulties with meth is that there’s not an immediate antidote, such as naloxone for opiate users. She said the drug is like “cocaine on steroids” in terms of its detrimental health effects.

“Crystal meth is one of our most potent stimulants,” she said. “It puts our sympathetic system on overdrive. Body temperature increases, your heart rate increases – it’s putting people at risk for heart attacks and arrythmia.”

Continued use, she said, also results in poor nutrition, greater risk for destructive behaviour and STIs, ongoing mental health issues, and medical complications over time.

The solution, she said, isn’t going to be easy, and is going to depend on multiple facets – from rehabilitation facilities, to healthcare providers, to police, to families, to users themselves – to get on the same page and work together toward an answer to the crisis.

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.