“F@#k Batman” is an odd sentiment to launch a DC TV series with, but a closer look at the history of the Teen Titans franchise and its impact on superhero storytelling reveals that “F@#k Batman” holds the potential to be a profound sentiment, one that is life-changing within a genre that traditionally avoids the very concept of life-changing.

Based on Reddit threads, YouTube comments and Tumblr posts, the internet has some strong opinions about the premiere of the Titans TV series that is helping to launch DC comics’ new video-on-demand streaming service.

Get breaking National news

READ MORE: Transgender activist Nicole Maines to star as TV’s first transgender superhero

The linchpin of the marketing surrounding the series, and the source of many of these social media debates, is a line that is featured prominently in the trailer, in which Robin says “F@#k Batman!”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-PPofXaJ4goThe past and present unite

At its core, the “F@#k Batman!” sentiment represents a change to the status quo. In 2018, a Robin who is “so over” Batman is in keeping with elements of the 1980s run of the Teen Titans comics, in which characters were allowed to grow in a way that had previously been prohibited.When asked about “F@#k Batman,” Titans writer and executive producer Geoff Johns connects the F-bomb line to the spirit of the 1980s Teen Titans comics. Because those comics changed the way we tell superhero stories in print, that could be a very good thing. If Johns is right about that connection to the ‘80s comics, then we might see the Titans TV series change the way we tell superhero stories on screen.While superhero stories seem simple on the surface (bright costumes, big muscles, lots of punching), the truth is actually deceptively complicated. So how do superhero stories work?READ MORE: Chadwick Boseman gives his MTV award to Waffle House hero James Shaw Jr.Umberto Eco & the myth of Superman

In 1972, the famous author and scholar Umberto Eco sought to define the unique ways that character and time operate within superhero comics.In his paper, “The Myth of Superman,” Eco notes that:“…[the superhero] possesses the characteristics of timeless myth, but is accepted only because his activities take place in our human and everyday world of time. In order to have that mythic quality, the superhero can’t grow or change in significant ways, but in order to be relatable to their readers, the superhero has to grow and change, just as people do.”Traditionally, comics lean toward the mythic. They also employ complex and unusual strategies to allow some life-altering events within the narrative. The most common approach is to reboot their universes every so often, thus restoring the status quo any time things have changed too much.

Robin’s transformation

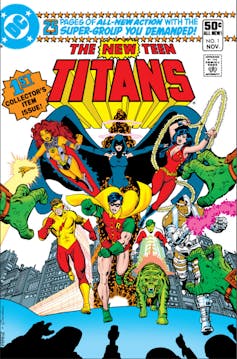

As a superhero team, the Teen Titans go back to the mid-1960s, but early versions failed to capture the hearts and minds of their readers. The series was cancelled twice before a 1980 relaunch found an audience.

A pressing need to reboot

As the Marvel Cinematic Universe starts to show its age, the question becomes whether it’s even possible to reboot it with so many intersecting franchises all sharing the same world. By imitating Marvel, the DC Cinematic Universe faces the same problem. On TV, DC’s Arrowverse is now six years old, and will also soon face these challenges.What these universes need is a way to tell superhero stories outside of the paradox that Eco describes, a way to allow our characters to age without aging out of the superhero they represent.Titans might not have the answer to this problem, but “F@#k Batman” could be the first piece of a good step, one that holds the potential to take our culture’s fascination with superheroes in a new direction once again.J. Andrew Deman, Professor, University of Waterloo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments