One Monday morning a few months ago, a man who works as a forklift operator at a metal scaffolding plant in the U.S. arrived at work.

Before he could start his day, he had to take a short test, basically a video game, designed to pick up on impairment. He failed, and was asked to explain himself.

It turned out that the issue wasn’t drugs, or alcohol, or extreme fatigue (which the test was originally designed to detect) but grief.

“He lost a close family member over the weekend, showed up Monday morning determined to work, but was still so emotionally distracted that he couldn’t concentrate,” explains Carol Setters of the company that makes the Alert Meter test. “So they took that person off of his safety-sensitive job for the next few days until he could recover emotionally.”

The concept is simple, but Setters says it solves many of the problems with traditional workplace drug and alcohol testing based on urine tests.

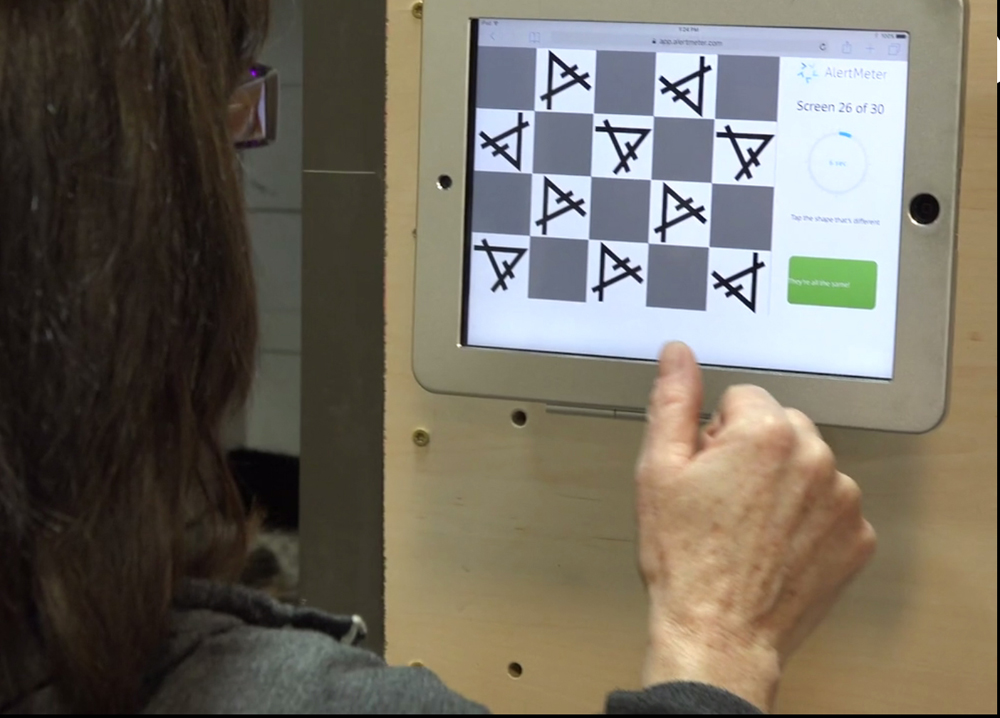

Every day, in a workplace that adopts the system, employees in safety-sensitive jobs do a short test that measures their ability to classify shapes quickly and accurately. The system compares the result to that specific person’s past results, recognizing that people have different abilities. An unusual result is flagged for the company.

People’s results are unique enough that it’s obvious if one person takes the test for someone else, Setters says.

Urine-based tests are intrusive, unpopular with employees and don’t measure many kinds of impairment well, Setters says.

“It doesn’t do anything for the relationship between management and employees if you show up and you have to stand in a line with a cup, and you can’t leave the line because you might get something to help you pass the test. It’s not good for employees and management.”

Urine tests can be used to measure the THC found in marijuana, but can’t measure marijuana-related impairment — which is only loosely connected to THC levels — at all well. They also aren’t good at looking at multiple substances (like marijuana and alcohol) that may each be present at moderate levels but acting powerfully together.

Get weekly money news

WATCH: Many industries in Saskatchewan use routine drug testing on their employees for safety reasons

As well, they miss non-chemical impairment, like fatigue. (A 2016 study showed that drivers who had less than five hours of sleep were 11.5 times more likely to get into an accident than those who had slept for seven hours or more. It found that driving after 4-5 hours of sleep is equivalent in risk to driving at around the criminal legal limit of 0.08 per cent of alcohol in a person’s bloodstream.)

Former Ontario privacy commissioner Ann Cavoukian, who testified in court for Toronto’s transit union in its fight against random drug testing, calls the screen-based approach “very, very different.“

“They’re just answering these questions every morning, which doesn’t take very long. I think this is far preferable to bodily fluids, and as long as there’s transparency and consent associated with the use of this, From a privacy perspective, I think it’s fine.”

“So long as there’s transparency up front, employees are informed of this and why it’s happening, and it takes very little time, then the only concern I would have is what happens to the information.”

In a 2013 decision, the Supreme Court set national rules for workplace random drug and alcohol testing, ruling that employers have to be able to show that they have a widespread workplace problem with substance abuse to legally impose it.

“Mandatory, random and unannounced testing for all employees in a dangerous workplace has been overwhelmingly rejected by arbitrators as an unjustified affront to the dignity and privacy of employees unless there is reasonable cause, such as a general problem of substance abuse in the workplace,” the majority wrote.

Earlier this month, the Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal of an Alberta decision that allowed Suncor to subject employees in safety-sensitive jobs to drug tests.

A Massachusetts inventor has developed a similar system for drivers to assess their own impairment, which is also based on a game that has learned the driver’s baseline skill level. Much like Alert Meter, the phone-based app’s creator pitches it as better at spotting fatigue, and impairment from multiple substances.

READ MORE: Too stoned to drive? This app will warn you

“It’s all about performance,” Setters says. “That’s the only thing you’re really concerned about: can this person perform well and safely?”

“That’s why we test their performance as opposed to their body fluids.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.