The 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment is often held up in popular culture as proof that good people will slip into “evil” behaviours if they are put into “evil” roles.

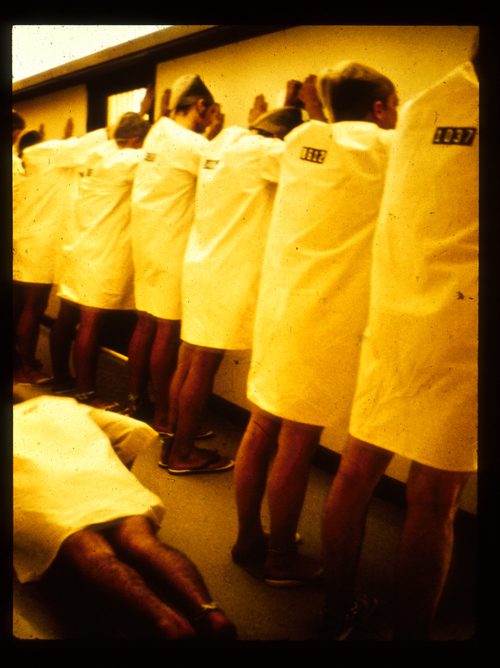

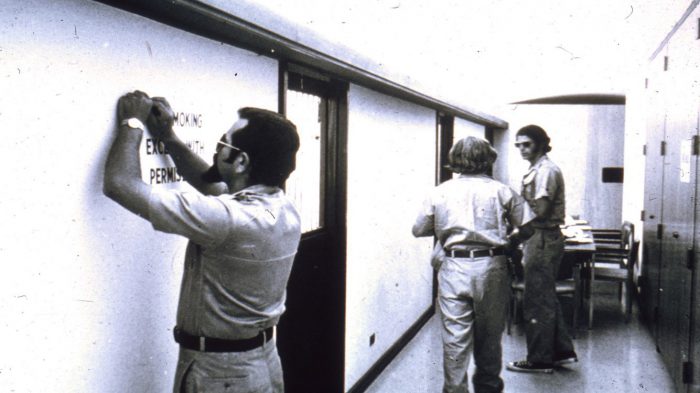

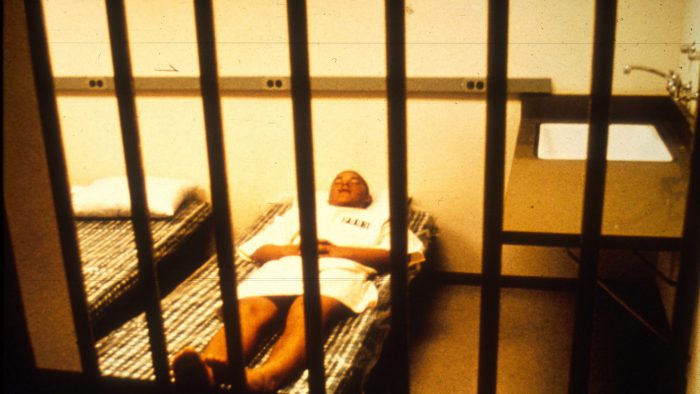

The experiment enlisted 18 college-aged men and divided them up evenly as either “guards” or “prisoners” to occupy a fake jail underneath Stanford University for two weeks. The fake guards soon started living out their roles, treating the “prisoners” harshly and employing cruel tactics to instil obedience.

Lead researcher and psychologist Philip Zimbardo characterized the results as proof that circumstances could be used to induce good people to do evil things.

“In only a few days, our guards became sadistic and our prisoners became depressed and showed extreme stress,” Zimbardo once said of the experiment.

The reality TV-style experiment was initially supposed to last two weeks, but was stopped on the sixth day because the subjects were mentally unraveling.

Or so the story goes.

New information released on Stanford’s website has cast major doubt on the experiment’s authenticity, and on its wide-ranging implications about human psychology and behaviour.

The most damning piece of new evidence is a recording of one of Zimbardo’s researchers explicitly coaching a “guard” to be more brutal to the prisoners, experts say. That runs counter to the long-standing narrative that the guards simply started behaving badly on their own.

“It completely blows them out of the water,” psychologist Alex Haslam of Queensland University, told Global News.

“I think every single textbook in social psychology is going to have to be majorly revised.”

New York University psychology professor Jay Van Bavel, who also listened to the tapes, says he plans to completely change the way he presents the experiment in his intro-to-psychology courses.

“In terms of science, we’ve always known it was pretty shoddy,” he said.

“A lot of us didn’t realize how bad it was.”

Here’s why a study about fake prisoners and fake guards appears to have produced fake results.

Researchers were coaching the guards to be ‘tough’

Tapes from the experiment point to obvious researcher interference, including an incident in which a guard was coached to be more cruel.

“We really want you to get active and involved,” researcher David Jaffe can be heard telling one guard, in an audio recording posted on Stanford’s website. Jaffe was part of Zimbardo’s team, and served as the warden during the experiment.

“We really want to get you active and involved because the guards have to know that every guard is going to be what we call a ‘tough guard,'” Jaffe said. “And so far…”

“I’m not too tough,” the guard said.

“You have to kind of try and get it in you,” Jaffe said.

Van Bavel says he was astonished to hear Zimbardo’s team interfering with their test subject to influence his behaviour.

“They were repeatedly pressuring him to do exactly what they wanted him to do, which in a psychology experiment is totally unheard of,” he said.

“He’s framing it as if the guards are part of the experimental team — that the guards and the experimenters are working together to produce some output.”

Haslam says this moment was the “smoking gun” he’s been seeking for 15 years, after his attempt to re-create the experiment produced very different results.

Haslam re-staged the experiment in 2002 for a BBC documentary special, but the guards in his experiment “showed no inclination whatsoever to be brutal,” he said.

“We didn’t reproduce that core finding,” Haslam said.

Get weekly health news

Haslam and his research partner, Stephen Reicher, suspected there must have been researcher interference in the original experiment, but they didn’t have any proof of that until the Stanford tape was released last month.

“It’s wholly inconsistent with everything that Zimbardo and his colleagues have said,” Haslam said.

The tape itself was unearthed by French filmmaker Thibault Le Texier, who published a transcript of it in April. Stanford appears to have posted the recording online since then.

Haslam presented his analysis of the tape to several psychology professors at NYU earlier this week, where the revelations inspired several in the audience to share their views online.

NYU professor David Amodio, who was in the audience, pointed out that the experiment was never published in a reputable scientific journal.

“I don’t think it’s scientific fraud in the typical sense,” he tweeted. “The (Stanford Prison Experiment) was never considered to be scientific. It’s typically presented in classrooms as a demonstration, not an experiment, and as a notorious case of ethical malfeasance.”

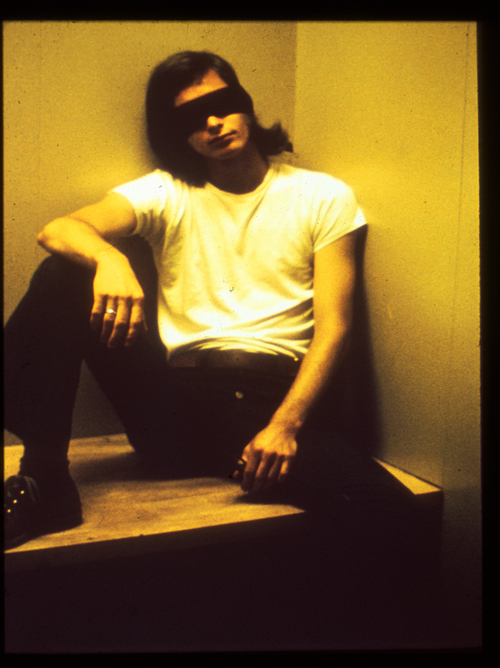

Participants were ‘acting’

Several “prisoners” from the study recently told writer Ben Blum they were playacting for the benefit of the experiment. Blum published their comments in a blog post on Medium.

Among those who have come forward to debunk the experiment is Douglas Korpi, a former “prisoner” who screamed, “I’m burning up inside!” from inside a dark closet during the experiment.

LISTEN: Writer Ben Blum discusses the Stanford Prison Experiment

Korpi told Blum he was putting on a show for the researchers.

“Anybody who is a clinician would know I was faking,” he said.

“I’m not that good at acting. I mean, I think I do a fairly good job, but I’m more hysterical than psychotic.”

Korpi said he agreed to participate in the study because it was a paid gig, and he thought it would give him some alone time to study for his Graduate Record Exam.

He described the experiment as a “very safe situation,” and said he only became distressed when the guards repeatedly refused to give him his study materials.

Two other former prisoners said they only became upset when they were prevented from leaving.

Dave Eshelman, whom the study described as “the most brutal of all the guards,” said he treated his position as an acting role. Eshelman faked a Southern accent and went by the nickname “John Wayne” during the experiment.

“Where had our ‘John Wayne’ learned to become such a guard? How could he and others move so readily into that role?” Zimbardo wrote in 1971.

The real lesson

Van Bavel says it’s tempting to throw out the Stanford Prison Experiment entirely, but there’s no way to delete it from the zeitgeist, because it’s appeared in countless textbooks and inspired several films.

“You have generations — 45 years of people who have learned about this — that are walking around with this knowledge, and it’s in all our texts,” he said.

Van Bavel recommends high school teachers avoid the subject altogether and leave it to the more critical approach of a university course.

Haslam also recommends reframing the experiment through a different lens.

“The standard account has no credibility whatsoever now,” he said.

Both Haslam and Van Bavel suggest the real lesson behind the Stanford Prison Experiment is not that humans will blindly conform to a given role, but that people can be talked into doing bad things by a strong-willed leader who makes them feel part of a righteous cause.

Haslam described the experiment as a perfect example of what happens in tyrannical regimes.

Haslam says in a tyrannical system, the leader first convinces his subjects that they’re part of an “in-group,” and that they need to sometimes perform terrible acts to protect their more noble cause.

In the case of the Stanford Prison Experiment, the guards were made to feel part of the experiment, and they were told to brutalize the prisoners for the sake of science, Haslam said.

“He tells them that the act is actually worthy, that we need to do this to protect the in-group and advance its interests,” Haslam said.

“So while it may be something you would rather not do, it’s actually essential for this noble project in which we are engaged.”

Van Bavel points out that Jaffe can be heard repeatedly using the word “we” with the guard, in a clear effort to make him feel part of the group.

“I’ve never seen anything remotely that shady,” Van Bavel said.

‘A great story’

The Stanford Prison Experiment was never published as a peer-reviewed, scientifically-sound study, but it gained popularity because Zimbardo knew how to sell it to the media. That included staging fake arrests of the prisoners for the benefit of TV cameras, and courting the New York Times for a lengthy piece about the experiment in 1973.

Zimbardo also recorded much of the experiment, which later became a documentary and a Hollywood movie.

“He was selling something really well that had the shakiest possible foundation,” Van Bavel said.

“It’s like a snake oil sales pitch.”

Zimbardo rode the Stanford Prison Experiment to tremendous fame within the psychological community. He’s written several books, delivered multiple TED talks and won numerous awards for his work in the field of psychology.

Van Bavel says the 85-year-old Zimbardo is regarded more as a “salesman” than a scientist within the psychology community today, but it may be difficult to correct the record on a view he’s been pushing for nearly half a century.

“This has been embedded in people’s minds as a core assumption they have about human nature,” he said.

“It’s a great story,” Van Bavel said. “[But] I feel like this is finally going to be the nail in the coffin that kills it.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.