“Many people feel it is open season on LGBTQ people,” Dr. Kristopher Wells, an associate professor with the Institute for Sexual Minority Studies and Services at the University of Alberta began.

“Increasingly, we’re seeing this change in society, we’re seeing much more LGTBQ visibility, but often with that visibility, we sometimes see the backlash, so we’ll see spikes of violence and discrimination,” he continued.

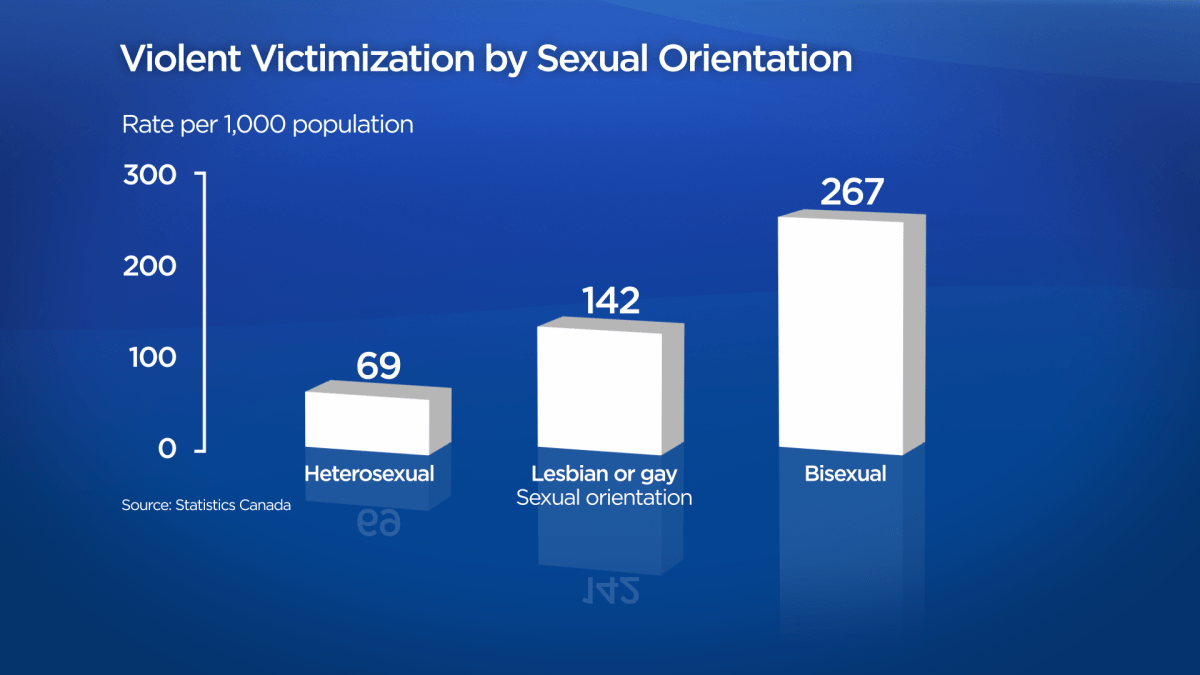

Statistics Canada released information on May 31 from the 2014 General Social Survey that found for every 1,000 straight Canadians, 69 reported they had been the victim of either sexual assault, physical assault, or robbery.

That number jumps to 142 for lesbian and gay Canadians and skyrockets to 267 for bisexual Canadians.

“Sexual violence against LGBT people in general really does come down to wanting to control people’s sexuality,” Rachel Loewen Walker, the executive director at OUTSaskatoon argued.

“I think LGBTQ young people are often in a position of double jeopardy. They want to come out, and they want to find community and find support, but at the same time they know the more visible they are, the more likely they are to experience victimization,” Wells said.

“Violence is a very real reality for them, particularly young LGBTQ people,” UR Pride Centre executive director Jacq Brasseur added.

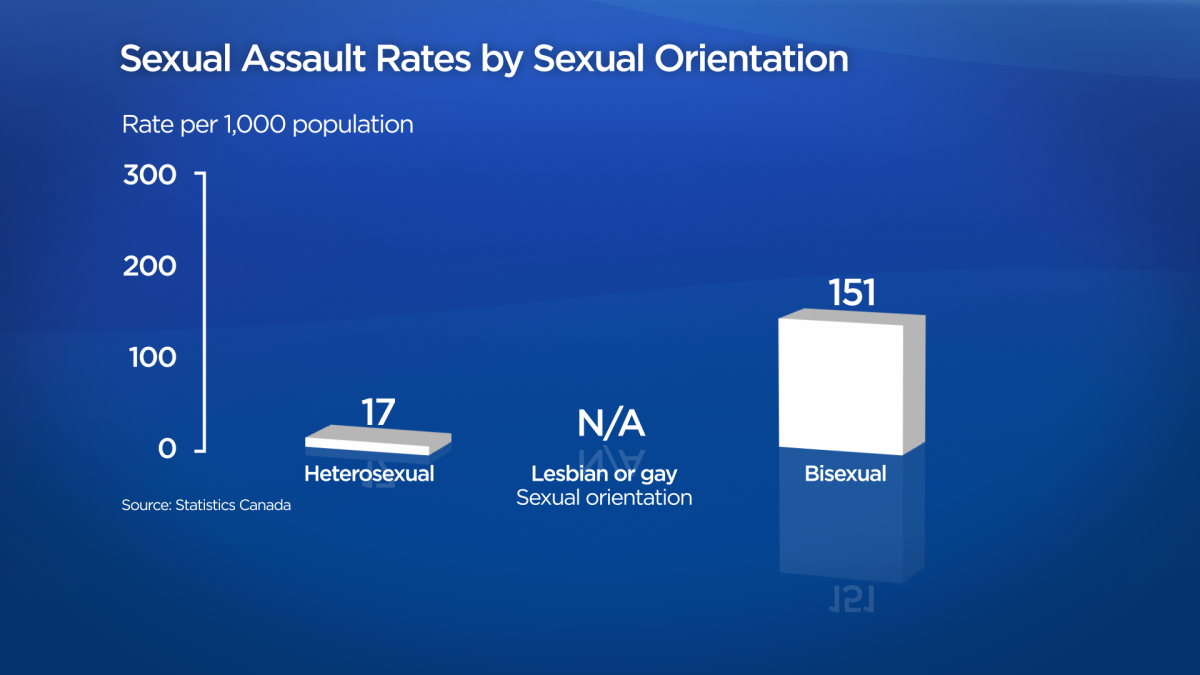

Bisexual women were particularly at risk; they’re seven times more likely to be victims of sexual assault than straight women.

Even though the number of victims has been declining since 2009 for lesbian and gay Canadians, they remain unchanged for bisexual Canadians.

Get daily National news

Experts said this is because of stereotypes in both the queer and heterosexual communities.

“The idea that bisexual people are hypersexualized, all the time, and that they are always down to have sex, I think perpetuates a lot of really harmful stereotypes, and ends up leading to bisexual people experiencing violence,” Brasseur, who identifies as bisexual, asserted.

“As the research shows us, bisexual youth are even in a more precarious position. They may be rejected from their lesbian and gay communities because they’re not accepted because of stereotypes, and from the heterosexual community they’re also rejected. They’re caught between worlds with no avenues of support,” Wells noted.

The result is a group of individuals experiencing violence more frequently, but reporting it less. According to the Stats Canada report, the rate of self‑reported violent victimization of lesbian and gay individuals decreased by 67% between 2009 and 2014. This is compared to a decrease of 30% for heterosexual individuals.

One potential reason for this is the stipulation that reporting these crimes means sharing personal, often secret information.

“They may be worried about being re-victimized if they reach out to the police or teachers because it requires them to out themselves. That’s sometimes the power of the closet, it doesn’t allow you to reach out for support,” Wells said.

In her work with OUTSaskatoon, Loewen Walker noticed a similar trend.

“I know that amongst a lot of the young people that we work with, we do hear of a number of incidences of sexual violence, of unsafe experiences, and they’re uncomfortable reporting those because then they would also have to come out. Whether that is to their friends, their parents or to the police officers themselves; if they’re not ready to come out, then they’re not going to share that story,” she explained.

The Regina Police Service (RPS) has initiated the Safe Place campaign, something they hope will make LGBTQ individuals feel safer when reporting a crime.

“We want to make sure we don’t have any antiquated business processes…something as simple, for instance, as reporting forms that offer only two choices: male or female. We want to make sure if we talk the talk, we walk the walk,” RPS said in a statement.

RPS also has a Cultural and Community Diversity Unit, whose mandate includes outreach to Regina’s gender and sexually diverse community.

One program that is making a difference is Pride Home, a shelter specifically for LGBTQ youth operated by OUTSaskatoon. No similar safe-haven exists in Regina.

“”I think it’s creating a community and a space for these youth to go in a system where there wasn’t a place for them to go to previously,” Loewen Walker said.

“Knowing that they have a community, knowing that they have somewhere safe to go, it adds a layer of safety, of support, of thicker skin so they can face those hard experiences,” she continued.

Both Brasseur and Wells agreed with the need for dedicated safe spaces for LGBTQ individuals affected by violence, and all agreed it can’t stop at safe housing.

“We’ve made remarkable progress in our country, but we can’t forget about the work that still remains. A lot of that is structural work. We need our organizations to be bringing an LGBTQ lens to the kind of work and services they provide and ask are they being inclusive,” Wells said.

Comments