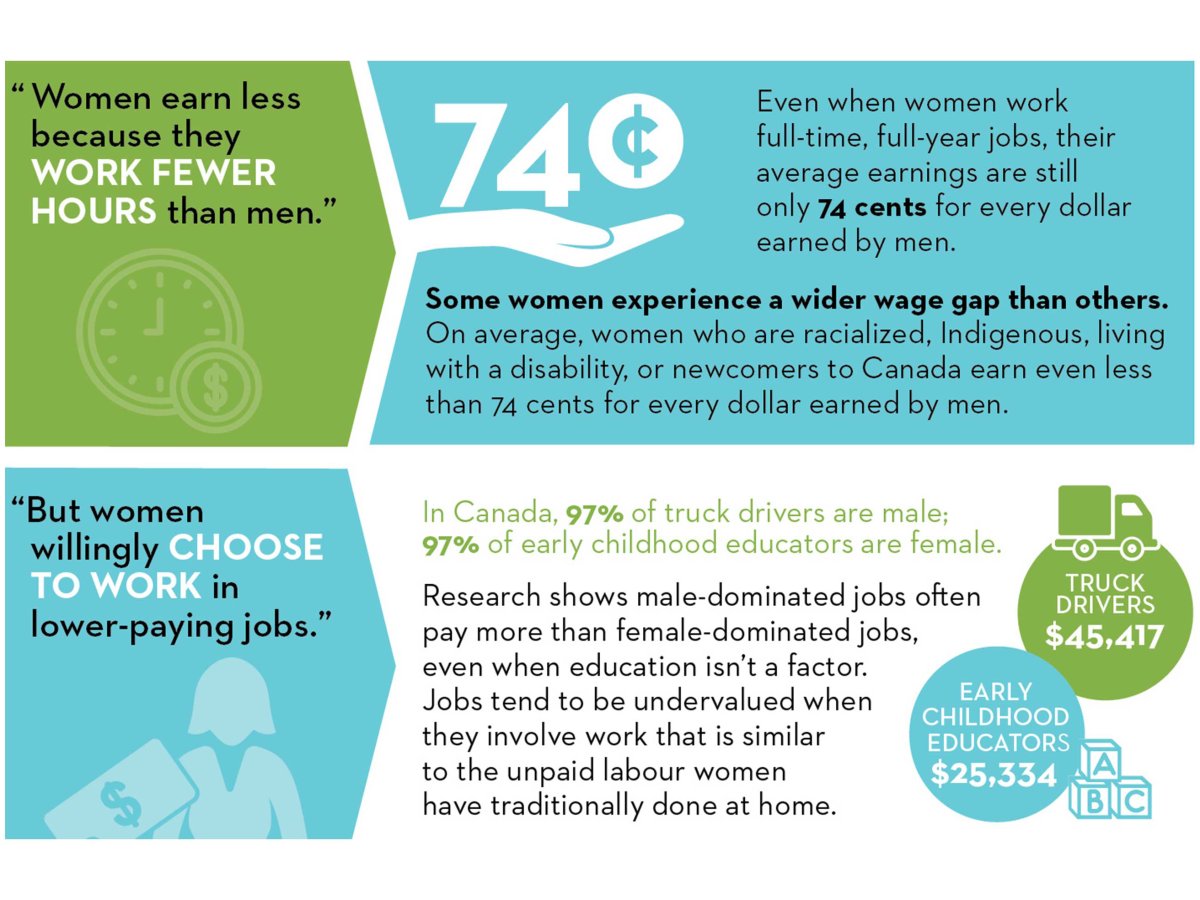

Tuesday marked the 22nd official Equal Pay Day, a day that’s meant to acknowledge and shine a light on the fact that across Canada and the rest of the world, women continue to earn less money than men. In Canada, women earn 26 per cent less than men — that’s 74 cents for every dollar.

READ MORE: The gender pay gap costs Canadian women almost $16,000 a year

But this fact (and the figures that back it up) are consistently argued and even denied by many people. In the spirit of clarification, Global News has broken down the common misperceptions around the gender pay gap and answered some of the most popular claims from opponents.

The gender pay gap is a myth

This couldn’t be further from the truth. For one thing, the pay gap can be measured in three different ways: by comparing average annual earnings (which is the go-to); by comparing full-time, full-year average annual income; and by comparing hourly wages. In all three scenarios, women earn less than men, albeit at different rates.

According to Survey Labour Income Dynamics (SLID) compiled by Statistics Canada in 2011 (the most recent data available), Ontario displayed a 31.5 per cent gap in average annual earnings. The 2013 Canadian Income Survey from StatsCan indicates a slight shrink in the gap to 29.4 per cent.

SLID data also shows a 26 per cent gap in full-time, full-year wages, and a 14 per cent gap in hourly wages.

Of course, it’s difficult to give precise examples of how these annual earnings differ — neither companies nor employees are terribly forthcoming with their salaries. However, a study conducted in 2014 by the Education Policy Research Initiative at the University of Ottawa showed that at one Ontario university, male students who did the same course of study as females and graduated at the same time, earned an average of $10,000 more in their first year after graduation than their female cohorts. Thirteen years after graduation, that gap widened to $20,000.

In essence, it tells us that women are undervalued from the get-go.

“People think the term ‘gender pay gap’ is exclusively about women making less money than men while doing the same work, and that’s part of it, but it isn’t the whole picture,” says Fay Faraday, a labour and human rights lawyer in Toronto and co-chair of the Ontario Equal Pay Coalition.

READ MORE: 14 factors lead to workplace gender equality — here’s how Canada measures

“There are other drivers. Yes, women are paid less to do the same job, but the numbers also capture the fact that female-dominated work is undervalued and underpaid relative to men’s work, and women overwhelmingly dominate part-time and temp work even though they want full-time work.”

But why focus on the most frightening statistic — the average annual earning gap —and not the others? Again, that comes down to big picture rationale.

- B.C. to ban drug use in all public places in major overhaul of decriminalization

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- 3 women diagnosed with HIV after ‘vampire facials’ at unlicensed U.S. spa

“You have to consider the impact sexism has on women throughout their lives, both in the workplace and outside of it,” says Sheila Block, senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. “Consider, for example, the educational choices that women are steered into, the unequal responsibility placed on child and elder care, the limited opportunities for advancement and that women negotiate smaller salaries — all this has a cumulative impact on women’s earnings.”

Women earn less because they work in low-paying jobs

A study conducted by researchers in the U.S. and Israel that looked at U.S. census data from 1950 to 2000 found that when women moved into occupations in large numbers, those jobs started to pay less even after controlling for education, experience, skills and race.

READ MORE: Gender equality in Canada: Where do we stand today?

However, the opposite is true for men. When they begin to enter an otherwise female-dominated field in droves, the salaries increase.

In Canada, women are paid less than men in 469 out of 500 occupations.

“Secretary used to be an entry-level job dominated by men, but when women starting doing these jobs, the pay dropped significantly and it became a dead-end job,” Faraday says. “More recently, if you look at a family physician, which was originally a male-dominated field, in the last generation it has become more female heavy and the wages have depressed. It’s now one of the lowest paid fields in medicine.”

Compare that to the example shown in the film Hidden Figures, she says. Computer coding used to be a female, and often racialized female job, but when men entered the field, the pay went up.

Even more interesting is the pay gap in nursing. A study published in the Journal of American Medicine found that although nursing is vastly dominated by women — they make up 92 per cent of the workforce — men still earn an average of $5,100 more than their female coworkers.

Women earn less because they mostly work part-time

What this comes down to isn’t choice, but rather lack of choice.

Statistics show that women who work part-time jobs do so because they have other responsibilities that preclude them from working full-time, including childcare.

In 2009, nearly one in five female part-time workers cited personal or family responsibilities as the reason for working part-time. Of them, 13.4 per cent said they worked part-time because they had children to care for, whereas only 2.3 per cent of men said the same.

“This is a direct result of lack of access to affordable childcare in addition to systemic discrimination that says that it’s women’s work. That’s why access to affordable childcare is the critical tool in helping to close the pay gap,” Faraday says. “And it’s something that literally has been recommended since the 1970 report from the Royal Commission on the Status of Women.”

In addition, 25.9 per cent of part-time female workers said they want full-time work, but can’t find it.

Women earn less because they take time off to raise children

It is true that a woman who has a child and takes 12 or 18 months of maternity leave will earn considerably less in that time than a male counterpart. However, it’s also true that oftentimes, that same woman will pay an economic penalty for her decision for the rest of her working life.

“There’s some interesting data around job tenure that shows women are fairly similar to men in how long they work for the same employer,” Block says. “Women on average work in the same place for 93.7 months, and men for 94.9 months. What this tells us is that women’s participation in the labour force has increased, but there’s still a gap in wages.”

WATCH BELOW: Women face criticism whether they take maternity leave or not

This is as much an issue about women being penalized for taking time off to have children as it is about the societal perception of men’s involvement in childcare.

“Women spend twice as many hours on childcare as men do. We need a change in perception of paternity leave as well as in men’s behaviour in taking responsibility for childcare,” she says.

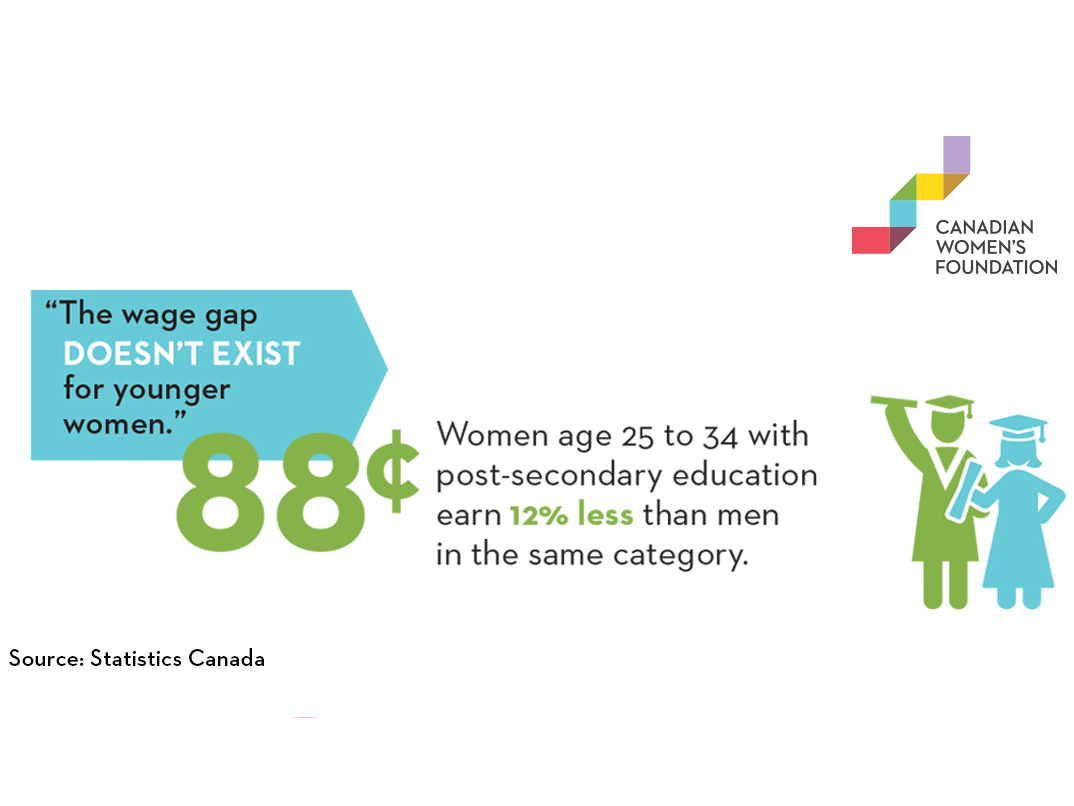

Women earn less because they’re not as educated as men

Since the early 1990s, women have made up the majority of full-time students enrolled in university programs; by 2008, 62 per cent of undergraduates were female. In 1997, women made up half of all Master’s graduates, and by 2008, they counted for 54 per cent.

So, no.

Women earn less because they don’t work in high-risk jobs

When people think of dangerous jobs, the first thing that pops to mind is likely one that involves carrying a firearm or running into a burning building. But what most don’t realize is that workplace violence is much more predominant in healthcare.

READ MORE: Canada must do better to close the gender gap but it won’t be easy: Bill Morneau

Recent statistics show that 56 per cent of lost-time injuries among registered nurses is due to workplace violence in the hospital sector.

“Even our ideas of what constitutes a dangerous job are infused with stereotypes of what danger looks like,” Faraday says. “We think of someone holding a gun, but we don’t think of a person who actually faces physical violence every day on the job.”

Comments