OTTAWA – The government is promising to cut in half the rate of active tuberculosis in Canada’s North within the next seven years, ahead of its plan to eliminate the disease by 2030.

The eradication plan will be lead by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the representative body of Inuit in Canada, and will focus firstly on preventing deaths related to tuberculosis among children. Health authorities believe that tuberculosis was the likely cause of a Labrador youth’s death in mid-March.

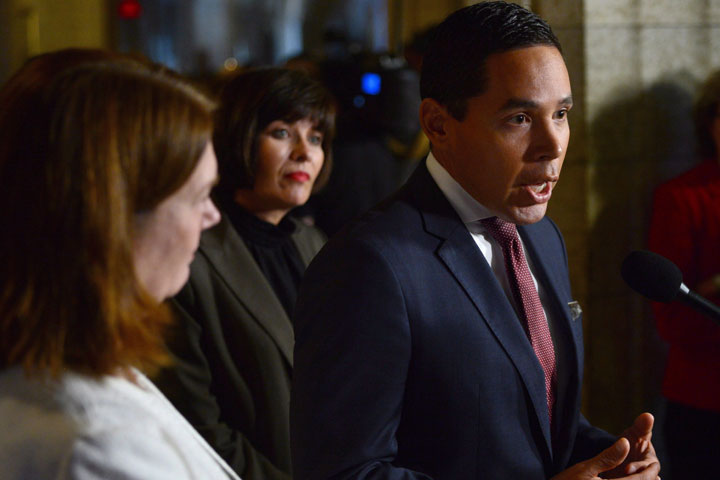

ITK President Natan Obed says the prevalence of tuberculosis in Inuit Nunangat, which is the Inuit-preferred term for the Arctic, is a legacy of the government’s historic indifference to Inuit health and well-being.

Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott says the rate of tuberculosis among Inuit has grown by more than 150 per cent over the past decade.

Philpott says it should never have taken Canada so long to make this pledge.

Get weekly health news

Tuberculosis is a preventable and curable bacterial infection that can lead to death and is more than 300 times more common among Inuit people than other Canadians.

Approximately 20 per cent of active tuberculosis cases diagnosed in Canada every year are in indigenous peoples. Most cases, around 70 per cent, are among recent immigrants to Canada.

Over 1,700 people were diagnosed with active tuberculosis in Canada in 2016. The disease is linked to poverty – spreading more easily in overcrowded conditions, poor housing and among people with unhealthy diets or compromised immune systems.

Comments