On Sept. 10, 2003, Faulino Deng beat up a Toronto roofing contractor and threatened to kill him.

A lanky former Sudanese soldier, Deng had only been in Canada 10 months and already he’d committed an aggravated assault.

Because he wasn’t a Canadian citizen, Deng was brought before the Immigration and Refugee Board, which ordered his deportation.

“Canada was offering you a safe haven,” a Refugee Board adjudicator told him later. “And, sir, you have done nothing but abuse the protection that Canada afforded you.”

Ordered Out But Still Here:

PART 1: Canada is failing to deport criminals. Here’s why it can take years, sometimes decades

That should have been the end of Deng’s brief stay in Canada.

But he’s still here.

Fifteen years after the assault, Global News found him living in a Scarborough bungalow owned by Toronto Community Housing. He has amassed dozens more criminal convictions, one for sexual assault, and is scheduled for trial next year on five charges, including two counts of trafficking, which he denies.

“Faulino is a criminal,” said the victim of the aggravated assault, who said Deng and another man beat him until he lost consciousness. Police alleged Deng used a piece of wood as a weapon. “Why they didn’t send him back, for God’s sake?”

Although Deng is under a deportation order, it has never been enforced by immigration officials, and neither have a growing number of others like it.

Countries refusing to issue travel documents

A Global News investigation has found the federal government has become increasingly ineffective at carrying out deportations for public safety and security reasons.

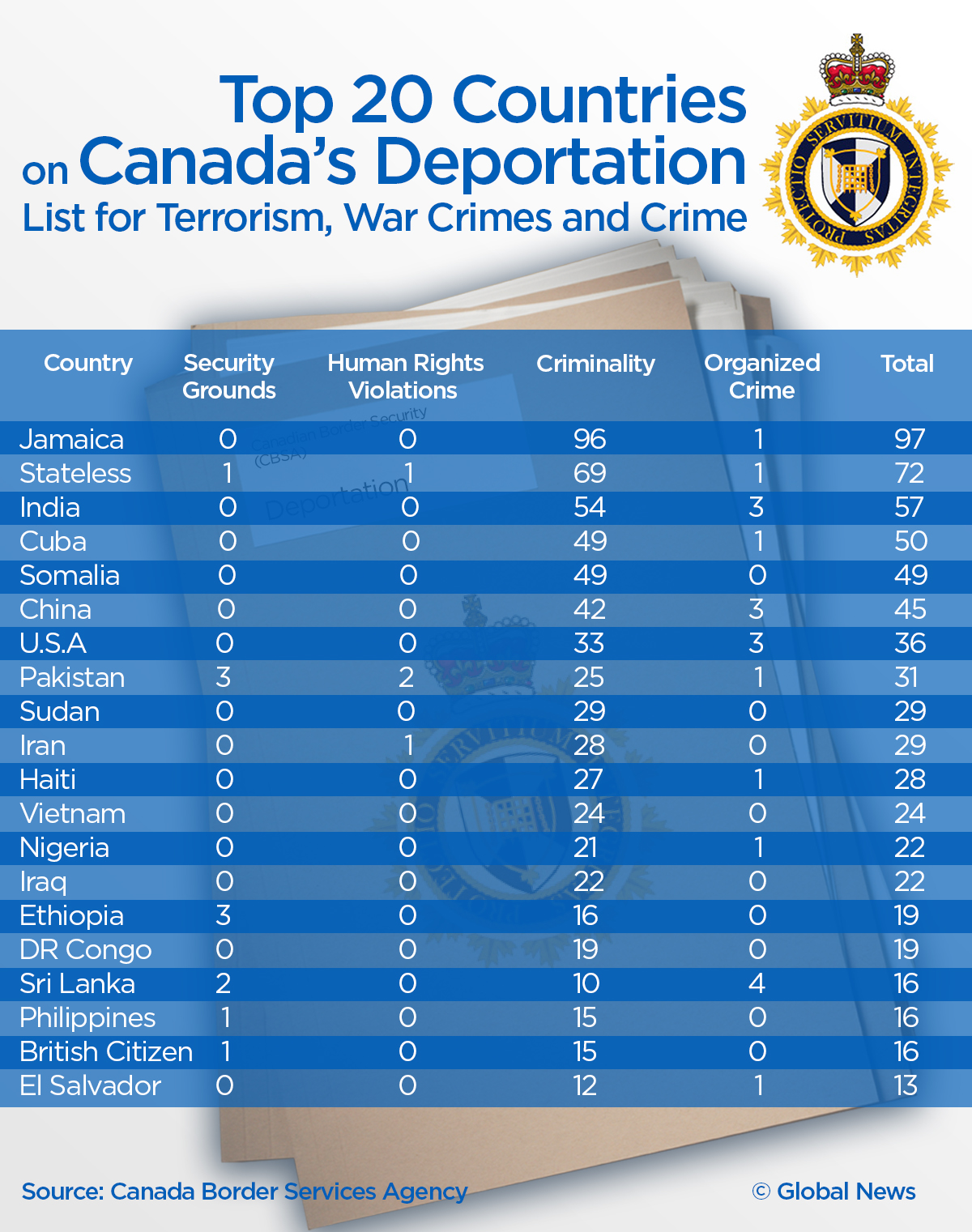

Removals of those who are supposed to be the government’s top priorities — foreign citizens under deportation orders for security, international human rights abuses, serious crimes and organized crime — have declined by a third since 2014.

Over that same period, the number of deportation orders issued by the Refugee Board on those grounds has remained relatively stable, and even increased slightly.

As a result, a growing number of foreign citizens remain in Canada despite having been ordered out on public safety and security grounds. In 2012, they numbered just 291. In early 2018, there were almost 1,200.

- Oil surges to highest price since 2023 as Iran war chokes Strait of Hormuz

- Americans view each other as morally bad, poll says. Canada is the opposite

- Alcohol sales in Canada just saw ‘largest’ annual drop since tracking began

- ‘A foreign policy based on short memory’: Carney continues push to diversify from the U.S.

Global News found some of them living seemingly ordinary Canadian lives although the government has alleged they had been members of terrorist groups or committed serious crimes.

For their part, those subject to Canada’s plodding deportation process can face years of uncertainty, and sometimes lengthy detention, while they wait to find out if they will be allowed to stay.

The federal government may be good at welcoming newcomers to Canada, but it’s become increasingly ineffective at getting rid of those who are not welcome.

“I don’t know when I’m going to leave or whether I’m going to leave,” Deng, dressed in a Toronto Raptors “We the North” sweatshirt, told Global News in an interview.

According to government policy, deportation orders are to be enforced “as soon as possible.” The government’s Level One priority is to carry out deportations ordered for safety and security reasons.

WATCH: Top countries refusing to issue travel documents for persons deemed public safety or security risk

But those types of removals have declined significantly. Only for organized crime did they go up last year, but overall they have dropped, and the backlog has swelled, government figures show.

“Over the past six years, there has been an increase in the inventory of outstanding cases due to the time required to complete these removals,” said Scott Bardsley, press secretary to Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale.

Explanations range from delays caused by appeals to problems determining the identities of deportees. Some can’t be expelled because they’re serving prison sentences, or because the dangers they could face in their home countries outweigh the risks they pose to Canadians.

WATCH: Faulino Deng discusses going through Canada’s deportation process

The government has lost track of some.

“There are a lot of people that just get lost in the wind,” said a Canada Border Services Agency officer who spoke to Global News on the condition of anonymity, citing fear of retaliation in the workplace. “And usually it’s the ones that are violent or dangerous that are hard to find.”

Get daily National news

But a list obtained by Global News shows the main obstacle is that certain foreign governments won’t issue travel documents allowing deportees to return, effectively making them Canada’s problem.

“The majority of cases within the CBSA removals working inventory originate from countries that either refuse to issue travel documents for their citizens or take a significant amount of time to issue proper documentation,” Bardsley said. “The CBSA continues to work with domestic and international partners to share best practices and develop engagement strategies to address countries that do not repatriate their citizens in a timely manner.”

The list identifies the worst offender as Jamaica, which is holding up 51 deportations of criminals because it won’t issue the required travel documents. Cuba is second-worst, followed by India and China.

“A lot of these people are hot potatoes,” said Chantal Desloges, a Toronto immigration lawyer and member of the Canadian Bar Association immigration section. “If you’ve got people that have been labeled as a security risk or have committed war crimes, their own country doesn’t want them back any more than we want them here.”

WATCH: Canada’s growing backlog of persons ordered deported for crime or security concerns

Kelly Sundberg, who spent 15 years in the CBSA, believes Canada’s deportation problems could be solved with diplomatic pressure and better staffing of immigration enforcement.

Sundberg left the CBSA in 2008. He obtained a PhD and is now an associate professor at Mount Royal University in Calgary. But he said some of the deportation cases he worked on before quitting government still haven’t been completed a decade later.

“Frankly the number of officers is far too low to manage the caseloads that exist,” he said.

That concerns him because his time in immigration enforcement showed him “there are some very dangerous people who have entered our country and live within our communities.”

The deportation system isn’t working because it’s overburdened, he said. Officers are “treading water” trying to keep up. “There needs to be a concerted effort and a concerted investment in this issue. It’s important and it has to happen.”

READ MORE: Canada has deported hundreds of people back to war torn countries

Canada needs to lean on governments that won’t issue travel documents, especially the ones that are recipients of Canadian assistance, he said.

“There is no excuse why our government is not being more assertive and more aggressive in its efforts to have documents issued and people who pose a risk and threat to our country to be removed.”

The CBSA would not answer questions about Deng.

Every three weeks, he is required to check in at the CBSA enforcement centre near Toronto’s Pearson airport. In interviews, he said he wasn’t sure what was happening with his case.

A former Sudanese soldier arrives in Canada

The government doesn’t seem entirely certain who he is. His name appears in court proceedings and police records variably as Faulino, Fanlino and Paulino. He said he was born in 1984, but Toronto police records say 1974, and the Refugee Board said he also claimed it was 1986.

The IRB was wary of Deng, concluding he was “not truthful in recounting his experiences in Sudan” and had likely altered the year of his birth to appear younger and “excite the sympathy of his audience.”

“They don’t know my situation,” Deng responded in an interview.

On his application for permanent residence, he said he had served in the Sudanese military from 1994 to 2000, according to the IRB. He told Global News it was actually 1995 to 1999.

He told the IRB his entire family was killed because his father was a church pastor in Khartoum. He said he survived the attack and was taken away by the military and jailed from 1997 to 2000.

“They came to us at home in my country, they hit my father, my mother, my children, everybody. They were all dead, they all died, I was shot as well. I was shot by four bullets and the Red Cross just caught me and they treated me and then they brought me through the UN to here,” he said at a hearing, according to the transcript.

WATCH: Ontario man, Faulino Deng, with more than 30 criminal convictions says he can’t go back to Sudan

However, he later described his father to the IRB not as a pastor but as “a prominent civil servant … an inspector in some directorate in Khartoum.” He later told Global News his father was among the “disappeared.”

Read back the transcript of the hearing in which he described how his family was killed in his presence, he said: “They say a lot of things that didn’t come out of my mouth.” He blamed his lack of English fluency for the discrepancies.

He said the army jailed him for not wanting to serve. A general freed him and someone who knew his father got him a passport. A family friend sold three cows and gave him the money to buy a plane ticket, he said. He said he flew to Damascus and the United Nations took care of the rest.

“I don’t know how I ended up in Canada,” he said.

READ MORE: 32,000 asylum seekers entered Canada, 6,000 work permits awarded, 9 deported: officials

In Toronto, Deng said he took an English-language course and worked for a roofer but his boss wasn’t paying him. “So I went to the guy and I said, ‘Where is my money?’” He said he had been drinking and pushed the man down.

Located by Global News, the victim of the assault said Deng did not work for him. He said he was in his backyard when Deng and another man arrived and beat him until he lost consciousness. A neighbor called police, saving his life, he said.

“I’m sorry for what happened,” Deng said.

WATCH: Former Sudanese soldier apologizes for past convictions

In 2004, Deng was sentenced to the nine months he had already served awaiting trial. But it wasn’t until 2007 that he was brought before the Refugee Board, which ordered his deportation.

He appealed the decision but the hearing did not happen until 2010, by which time he had amassed 29 criminal convictions. Assault with a weapon, threatening, cocaine trafficking and more assaults, the IRB said. The ruling rejecting his appeal was issued in 2011 — almost eight years after the crime that triggered his deportation order.

“Parliament has indicated an intention to prioritize public safety and security above other objectives,” read the decision on his appeal. “It has done so by emphasizing permanent residents’ obligation to behave lawfully while in Canada, by removing permanent residents from Canada with serious criminal records.”

He filed an appeal in the Federal Court; it was similarly dismissed.

But Deng still wasn’t sent home.

And his arrests continued.

READ MORE: Canada rejects hundreds of immigrants based on incomplete data, Global News investigation finds

The effort to remove him was sloppy at times. At one hearing, a government official said Deng had been convicted of “obtaining transportation by force,” and explained the crime “probably more commonly would be known as hijacking a vehicle.”

Court records, however, show he was actually charged with obtaining transportation by fraud after he was caught on the GoTrain without a ticket. He was also charged with assaulting the officer who arrested him. He served five days for both counts. Deng said he had been drinking.

The following year Deng was charged with 17 counts of cocaine trafficking and possession of criminal proceeds. He was convicted of three of the trafficking charges. The others were withdrawn.

Upon his release from prison in 2013, the CBSA detained him while it continued to try to deport him.

“The only time he does not seem to accumulate convictions is when he is in custody,” an immigration official told the Refugee Board.

“I think,” the IRB adjudicator told Deng, “it is time for you to realize you are going to Sudan.”

The deportation process

Deportation efforts moved so slowly, however, that while his case was being processed, Sudan divided into two separate countries, Sudan and South Sudan, further complicating his removal.

Sudan is among the countries that does not issue travel documents allowing the return of deportees. Canadian immigration authorities tried to get one from South Sudan, presumably because Deng is a Dinka, the largest tribe in that country.

But South Sudan would not cooperate, and with no sign he would get a passport any time soon, the IRB ordered his release from custody in July 2014 on the condition that he not use or possess drugs or commit further crimes.

“Yes, I promise that I will comply with all the conditions,” Deng, speaking through an interpreter, responded at his release hearing.

He was soon in trouble again.

A video posted on his Facebook page two years ago shows him smoking what he called “kush” and rapping about cocaine trafficking. “I’m in the kitchen, doing operation, mixing up white powder … I’m on the block all day. … Tell these police officers over there I’m back again, I’m back again officer.”

“That’s music talk,” Deng responded, when asked about the videos.

READ MORE: 32,000 asylum seekers entered Canada, 6,000 work permits awarded, 9 deported

The South Sudan embassy in Washington, D.C. did not respond to interview requests. Initially, the embassy told the CBSA it was not issuing travel documents due to “civil unrest,” according to government records. Then in 2015, it stopped issuing travel documents specifically for criminal deportations.

A notice on the embassy website said that “reception of former prisoners/inmates deportees from USA, Canada, and other countries” was suspended until the government developed a “comprehensive policy” on how to safely reintegrate them.

CBSA officers are supposed to refer cases to the Removal Operations Unit in Ottawa when they are unable to get a travel document. Global Affairs Canada may be asked to intervene. It’s unclear whether that has happened in Deng’s case.

Immigration lawyer Richard Kurland likened the travel document issue to a ping pong game that continues until one side concedes. “Question is, how long before someone blinks? Who wins? That person that gets to stay here. Who loses? Canadian society, because we’re at risk. We have a known criminal in our midst that we can’t get rid of.”

READ MORE: Canada deporting fewer people for terrorism, war crimes, crime

He believes foreign policy tools are the solution. “Additional CBSA officers is not the problem. The receiving country is the problem. And we have to squeeze and squeeze hard the interest of that receiving country, in order to get our way.”

“It could be diplomatically, enhanced trade sanctions, or even the imposition of a visa requirement on that country, stricter standards — unless that country takes back known criminals that are waiting for removal right here in Canada.”

Michelle Rempel, the Conservative immigration critic, said the problems needed to be addressed before Canadians lost confidence in the immigration system. “And frankly, I mean there are genuine public safety issues that you’ve raised there that are not acceptable,” she said Tuesday.

On January 24, 2018, Deng’s lawyer appeared in a Toronto courtroom to deal with his five latest charges, which date back to 2016 and include two counts of trafficking in a substance. The trial has been set for Feb. 11, 2019.

“He denies the allegations and is looking forward to proving his innocence at trial,” said his lawyer Robert Chartier.

Shown a list of his crimes and asked if he could appreciate why Canada didn’t want him in the country anymore, Deng acknowledged he had made mistakes.

“If they send me to South Sudan, it’s still going to be dangerous because there is civil war going on there,” he said. “God knows what is going to happen. I would love to stay here.”

He said he sometimes asks about the status of his case at the CBSA reporting centre and the officers tell him to get a travel document. “They tell me, next time I come maybe I’m going to hear something.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.