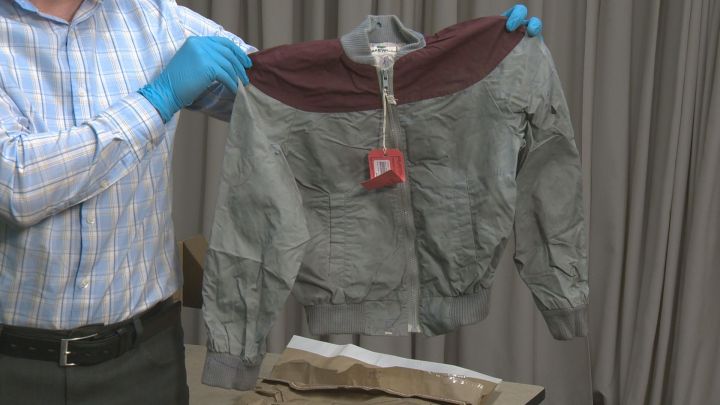

Standing at RCMP K Division Headquarters in Edmonton last Wednesday, an investigator held up a tiny grey jacket. It was obviously dated; dirt caked around its edges, blue pen marks, rips and tears and most notably, a red evidence tag on its zipper.

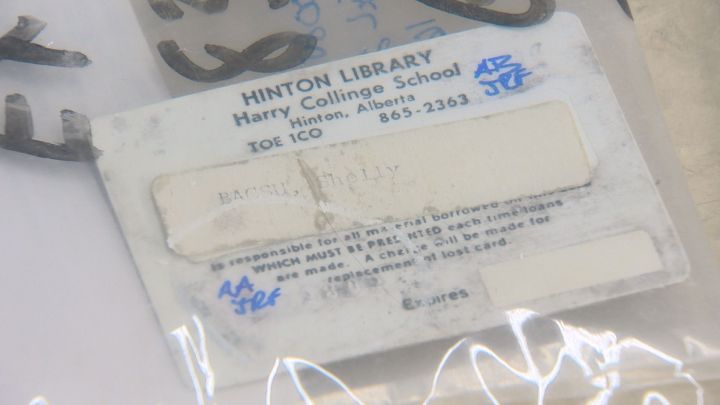

Inside the pocket was a library card that helped police identify its owner back in 1983.

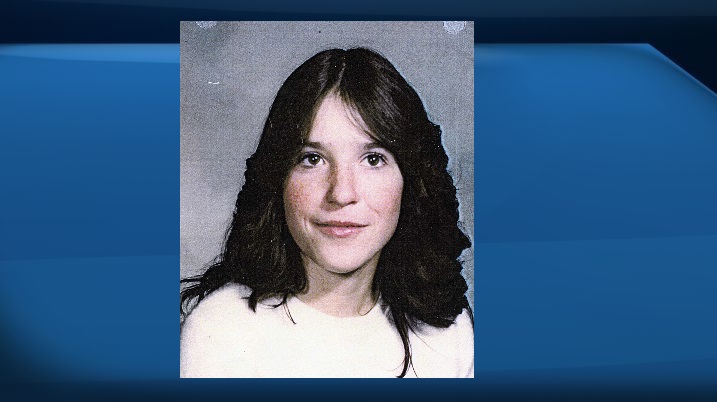

Her name was Shelly-Ann Bacsu.

The 16-year-old left her friend’s house in Hinton, Alta. more than 30 years ago. She was walking the seven kilometres home but never arrived.

“Based on that and the passage of time, we believe, unfortunately, that Shelly-Ann probably was a victim of foul play and her remains have never been found,” said Staff Sgt. Jason Zazulak, who’s in charge of the Historical Homicide Unit with the RCMP. “It’s very, very unusual for someone to leave no trail, no footprint.”

READ MORE: Historical homicide unit believes unrelated deaths of 3 Alberta women will be solved

More than three decades later, Bacsu’s family and police are still looking for answers.

Bacsu’s case is one of 237 unsolved murders in the province of Alberta.

“We’re ready to advance any case at any time,” Zazulak said. “We are always going to keep these open. We are always going to be open to new tips and information.”

It’s a difficult job. Once the Major Crimes Unit has exhausted all efforts in the search for suspects in homicide cases, they are turned over to the eight-man unit. They scour through the evidence again looking for new information.

Get breaking National news

READ MORE: 10 years since wildfire spotter Stephanie Stewart vanished near Hinton, Alta.

As technology advances, they audit the evidence, like in Bacsu’s case.

“Those items that were collected as evidence, they would have been subjected to whatever forensic tests were available at the time,” he said. “Now there are more robust tests that they can do looking for the presence of any suspect DNA that we could find on them.”

But it’s more than just DNA. The unit works closely with forensic laboratories to ensure any advancement means a re-evaluation of what they already have collected, like fingerprints, shoe prints or tire prints from a scene.

“The development of a database of different footwear has helped us over time,” Zazulak said. “The more cases we submit to those databases, over time, the more robust and useful the databases become.”

READ MORE: 49-year-old Quebec man arrested in 2002 death of young Alberta woman

- Shooting at Rhode Island ice rink kills 2 during youth hockey game: police

- Anti-feminist ideology ‘increasingly relevant’ to national security: CSIS

- Savannah Guthrie issues new plea for mother’s return as police clear family

- Tumbler Ridge shooting fuels misinformation about trans people, organization says

Investigators say time also plays a role in when witnesses may come forward.

“We may be dealing with witnesses who are dealing with times in their lives where they aren’t quite comfortable sharing what they know about a case,” Zazulak said. “Over time, their personal circumstances could change. So we want to keep those lines of communication open so that when they’re ready to share what they know, we are ready to receive it so we can move a case forward.

“If we get a new piece of information that comes forward, if it’s compelling enough, we would do a full audit of that case,” he added.

New information is crucial. Zazulak believes someone out there knows something about what happened to all 237 of the victims and they need that information to bring families closure.

“We all have, deep down, that sense of right and wrong,” Zazulak said.

“Over the passage of time, I think it really weighs on a person,” he added. “There comes a time when people want to move forward in their lives and I think now is the time for that.”

READ MORE: RCMP search for missing Mundare woman, last seen in November

The group is always using new techniques to keep the conversation about these cases public. The lead investigator in the case of a missing wildfire spotter is even using social media to help make progress in the case. His Twitter handle is @KerryShima_RCMP. It was an idea that was brought forward at a historical homicide conference in Regina.

The Historical Homicide Unit doesn’t do its work alone. Its members work alongside forensic laboratories, local RCMP detachments and victim’s services.

Officers try to keep in contact with families of victims at least once a year. Unfortunately, the message is usually the same: there’s no new information.

“We try to be upfront and honest about the status of our investigations,” Zazulak said.

But that doesn’t mean that the group loses hope.

If you have any information on any historical homicide case in Alberta call RCMP or Crime Stoppers.

Comments

Comments closed.

Due to the sensitive and/or legal subject matter of some of the content on globalnews.ca, we reserve the ability to disable comments from time to time.

Please see our Commenting Policy for more.