“She made recommendations to the priest …”

And that, mysteriously, is the start of an enigmatic medieval book that has baffled experts for generations — at least according to the Edmonton computer scientist who believes he’s cracked the baffling code of the Voynich manuscript.

“Once you see it, once you find out the mystery, this is a natural human tendency to solve the puzzle,” said Greg Kondrak of the University of Alberta’s renowned artificial intelligence lab.

“I was intrigued and thought I could contribute something new.”

LISTEN: The University of Alberta’s Greg Kondrak on deciphering the Voynich manuscript

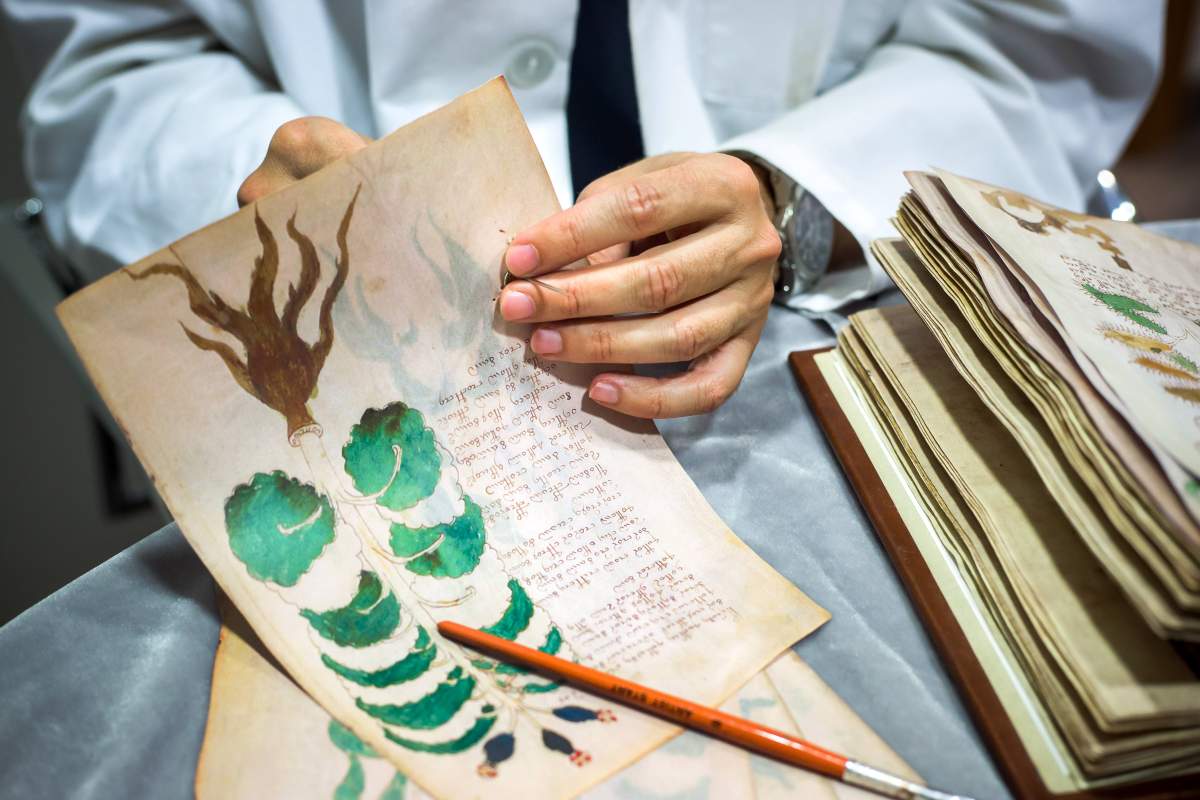

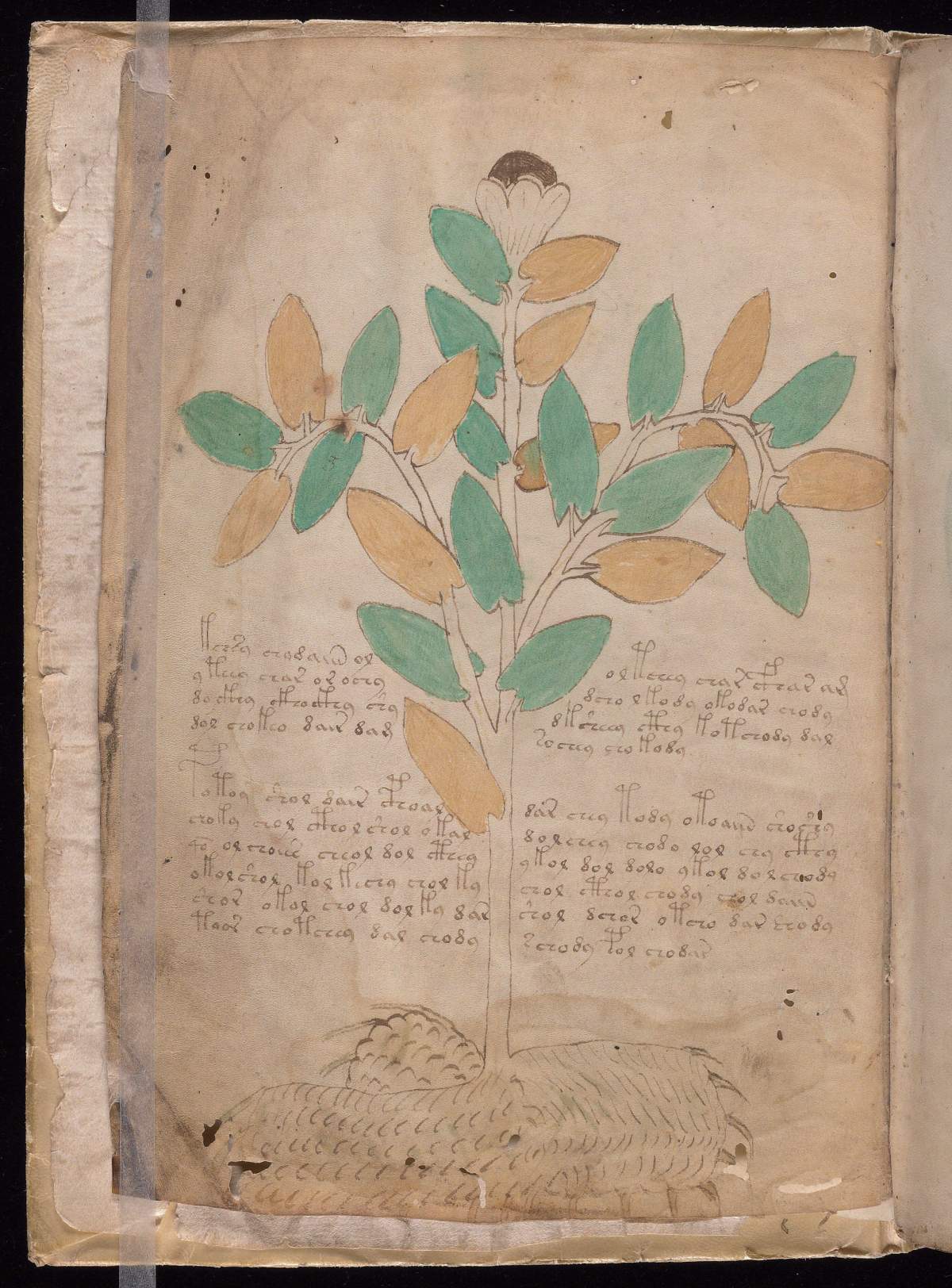

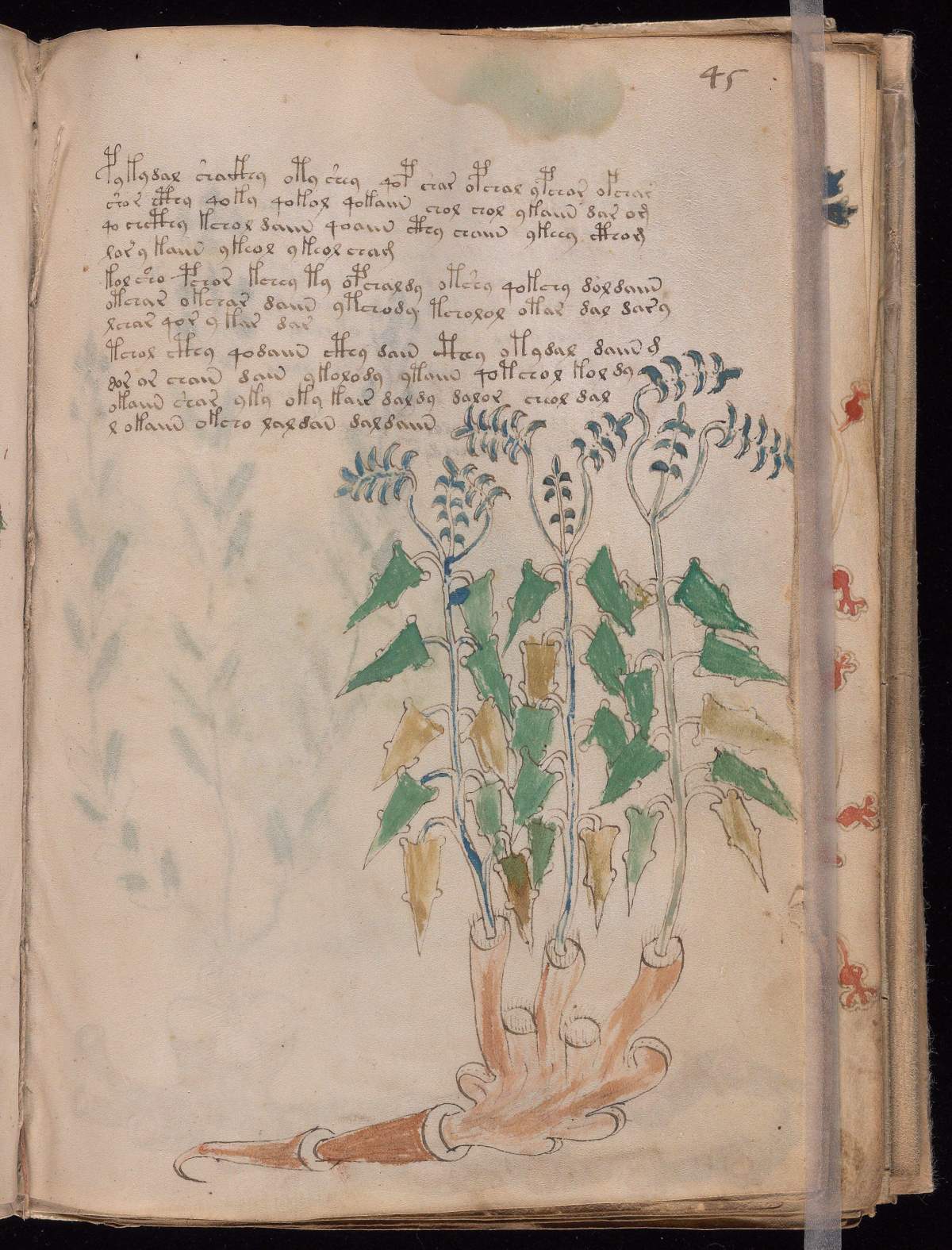

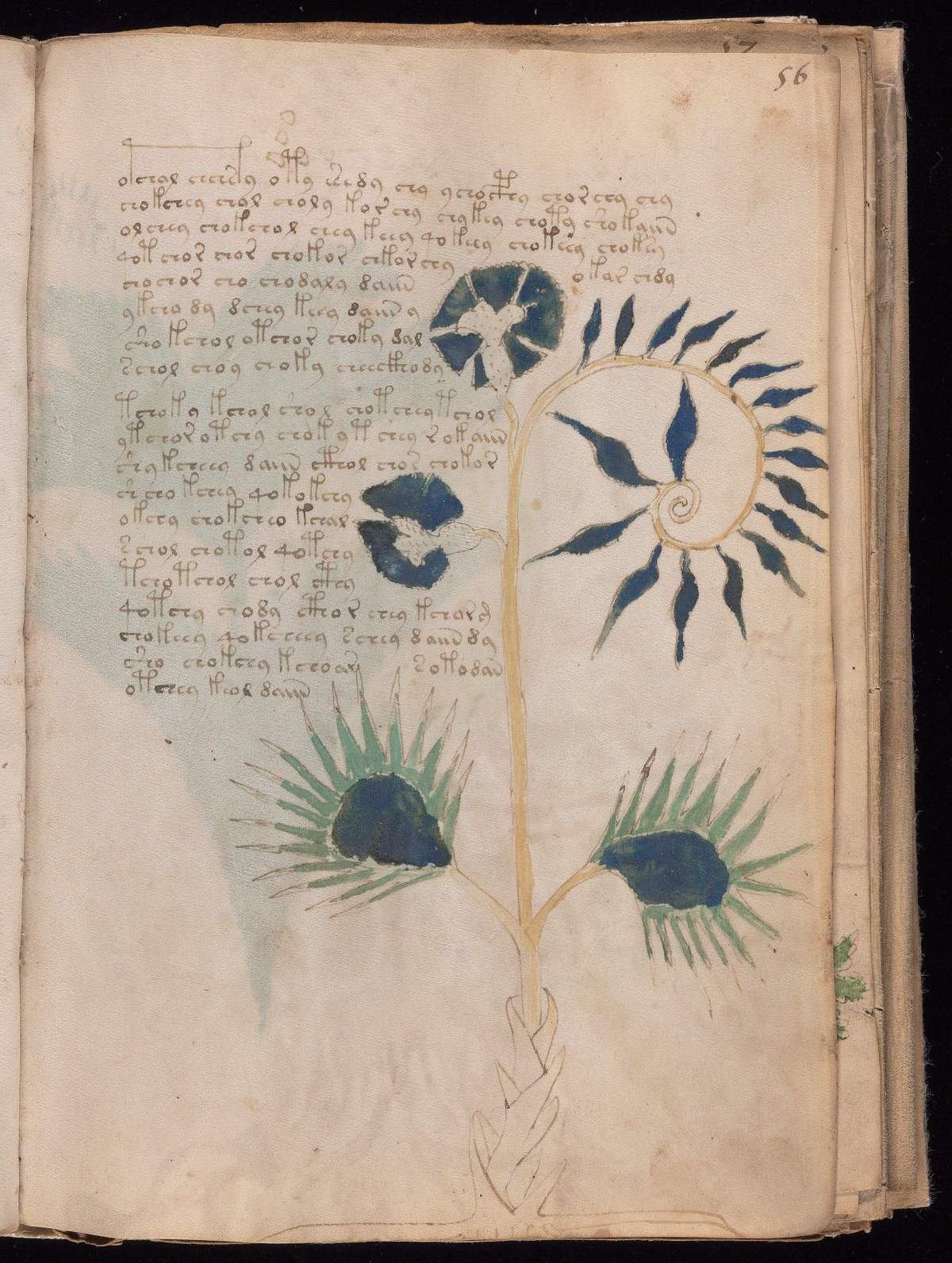

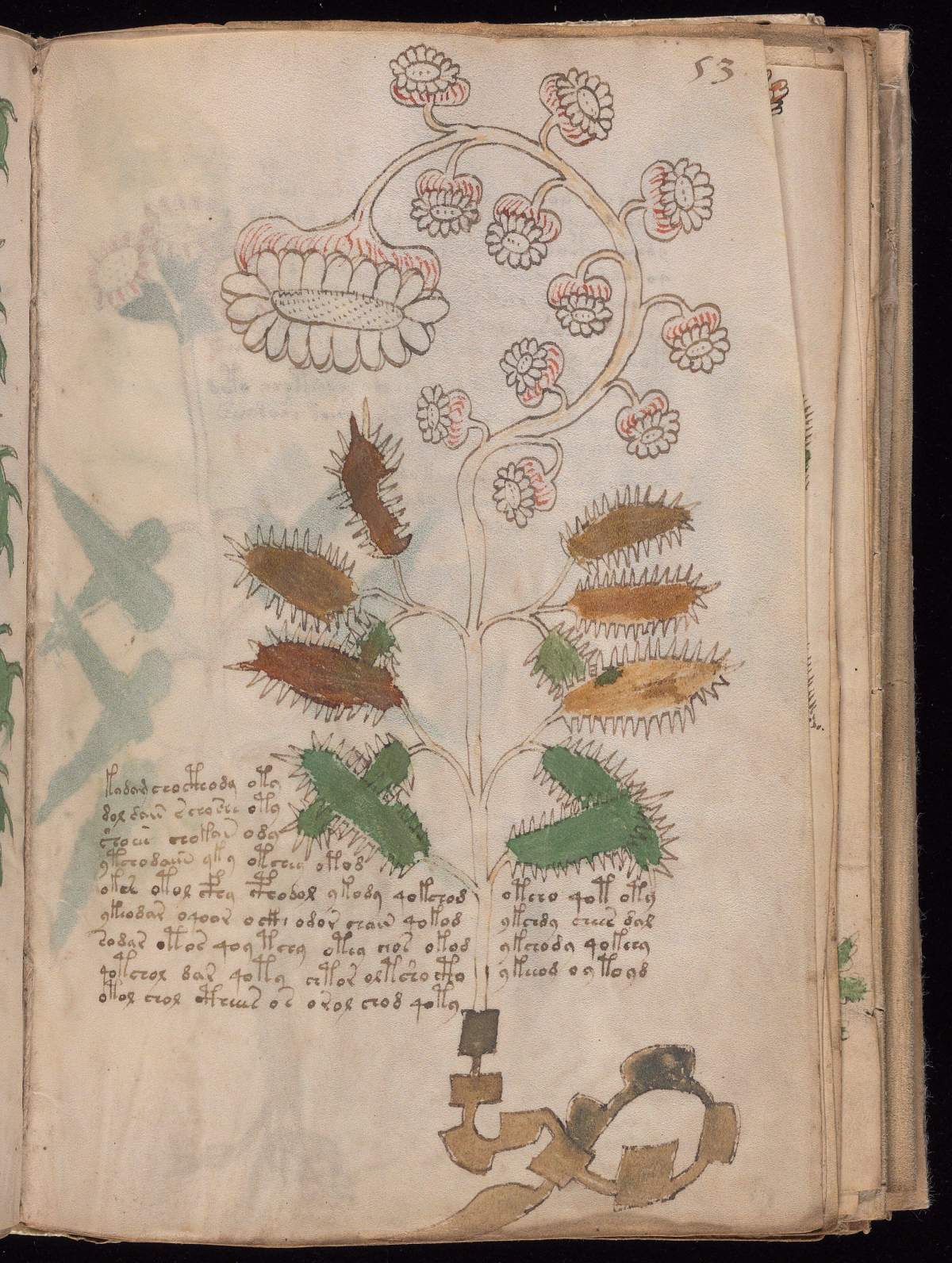

The Voynich manuscript has been carbon-dated to the early 1400s. It is thought to be some kind of document on women’s health, but because it is written in an unknown language, in an unknown script, scrambled by an unknown code, no one can say for sure.

Its 240 pages, now part of Yale University’s Beinecke collection, are heavily illustrated with plants, stars, planets and bathing women. Some plants match known species; some don’t. Some astronomical diagrams look like zodiac signs; some don’t look like anything from earthly skies.

No one knows what the dozens of naked women in various bodies of water are doing.

Its ownership can be traced back to the early 17th century. It surfaced in modern times when a collection of manuscripts from a Jesuit library in Italy was purchased in 1912 by a rare-book dealer named Wilfrid Voynich, who tried to interest someone in translating it.

Get breaking National news

Many were. None succeeded.

READ MORE: From Shakespeare to Atwood, the home of the largest rare book collection in Canada

At least eight would-be translators have declared success but were later debunked, the most recent of them late last year. The manuscript even frustrated the famed cryptographers of Britain’s Bletchley Park, the team that broke the Nazis’ Enigma codes.

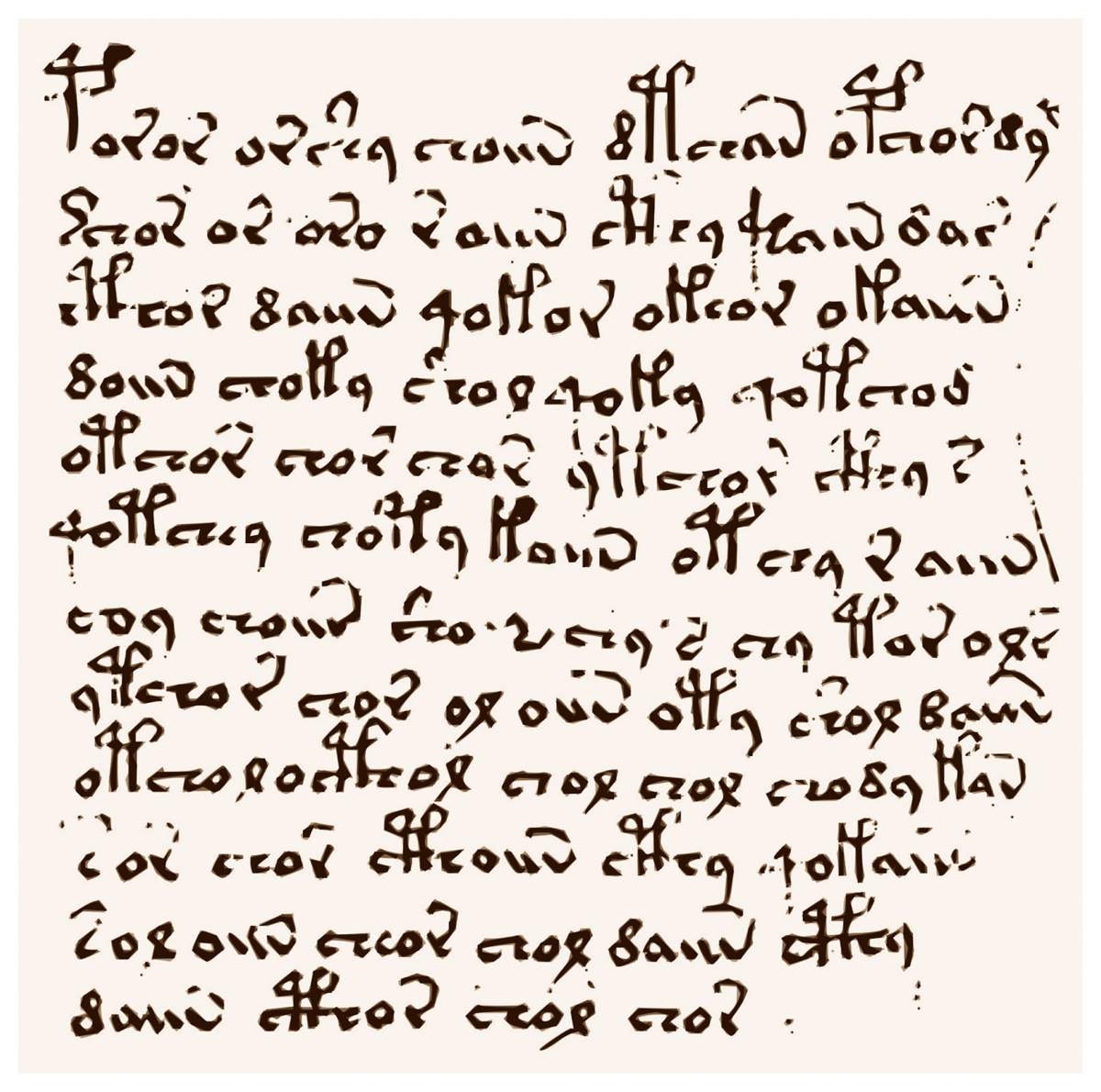

Guesses at the language of its text have ranged from a type of Latin to a derivation of Sino-Tibetan.

Kondrak thought powerful artificial intelligence programs could help. His university’s labs had already developed software that made world headlines by beating professional players at Texas Hold ‘Em, one of the most complex types of poker.

“The first step is to try and find out what the language is.”

He and his co-author Bradley Hauer took the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and translated it into 380 languages. Using a series of complex statistical procedures and algorithms, they were able to get a computer to identify the correct language up to 97 per cent of the time.

Putting the manuscript through the same statistical procedure yielded the hypothesis that it was written in Hebrew.

Then they went after the Voynich code. The letters in each word, they found, had been reordered. Vowels had been dropped.

Its complete first sentence, according to computer algorithms, is “She made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people.”

The first 72 words of one section yield translations that might fit in a botanical pharmacopoeia: “farmer,” “light,” “air” and “fire.”

Kondrak acknowledges the reception of his work by traditional Voynich experts has been cool.

“I don’t think they are friendly to this kind of research,” he said. “People may be fearing that the computers will replace them.”

But Kondrak said there’s much more to translation than feeding the Voynich into a computer. A human is needed to make sense of the syntax and intent of the words.

“Somebody with very good knowledge of Hebrew and who’s a historian at the same time could take this evidence and follow this kind of clue. Can we look at these texts closely and do some kind of detective work and decipher what can be the message?”

If it works, Kondrak suggests, similar methods could be used to translate scripts such a writing system used in ancient Crete. There is no shortage of mysteries, he said.

“One of our motivations was the ancient scripts. There are still ancient scripts that remain undeciphered to this day.”

Comments