It’s easy to ignore, until suddenly it’s not.

As the earth warms, Arctic and Antarctic ice sheets melt and sea levels rise steadily – just a third of a centimetre a year or so, but it adds up, and it isn’t slowing down.

What will our shorelines look like by the year 2100? Well, it depends – on how much the climate warms, whether air pollution goes on unchecked or reduces, on whether the West Antarctic ice sheet has begun an unstoppable collapse (the maps below assume it hasn’t).

But even under the most cautious scenarios, the shapes of coastal cities will change.

The worst effects will be felt in Asia, where Shanghai, Osaka and Hong Kong are under threat. Globally, 275 million people live below five metres above sea level, and 60 million within a metre.

But some communities on both of Canada’s salt-water coasts will start to feel the effects of rising sea levels, maps produced by Climate Central, a scientific non-profit based in New Jersey, predict.

The maps below show sea levels “locked in” by different levels of carbon pollution.

Here are two places in Canada, thousands of miles apart, that will see serious challenges – and questions about the value of land that may have expensive answers – as the century unfolds.

1. Richmond and Delta, B.C.

Even the most conservative flood maps show Richmond, Delta and parts of rural Abbotsford and Coquitlam permanently underwater by 2100.

CLIMATE CENTRAL

But it’s not going to look like that, predicts earth sciences professor John Clague, who teaches earth sciences at Simon Fraser University.

“It ignores the social reality that we protect areas like that from flooding and inundation, which has to be taken into account when we assess the risk that people face from sea level rise.”

Too many people live in the area and there’s nowhere else for them to go, given the constraints of Vancouver’s geography.

Instead, he argues, we are eventually going to be forced to spend billions of dollars on a massive system of flood defences.

“That’s critical real estate,” he says. “It’s home to 250,000 people who live basically at, or close to, sea level. It’s where the international airport is located, and we have one of the largest bulk export facilities in North America located on that surface. There are all sorts of reasons why that surface would be protected.”

Get daily National news

“I’m not going to live to see it, but it’s going to be a problem future generations have to face.”

A gradual sea level rise of 3.5 millimetres a year is easy to ignore, he says. The crisis would build slowly but express itself in a violent storm, driving the now-raised water levels.

Global warming, in addition to raising sea levels, causes more, and more drastic, storms.

“We don’t know if we’re seeing the largest, most severe storms that we can see. We think that the past is kind of a metric of where we’re going in the future. There are some scientists that think that as oceans warm we could experience unprecedented storms – frequent severe storms.”

“My guess is that we will spend $10 billion, given what’s at stake on that surface. The alternative is to abandon it.”

“But it’s going to cost us a huge amount of money to basically provide protection for the infrastructure and people who live there now.”

“You’re talking 250,000 people now, but it’s a rapidly growing municipality. By mid-century, when we’ll have to begin to take action on this, I can imagine it will be double that. So you’re talking half a million people, roughly. And where are they going to go? There isn’t enough space in the Fraser Valley to accommodate that number of climate refugees.”

Whether sea defences would work well into the 22nd century is open to question, though.

“This is kind of a disaster that’s playing out in slow motion, so people wouldn’t take it as seriously as they would the danger of an earthquake, but the implications of this are so large that it does require a concerted effort to deal with it. We can kind of postpone the inevitability of abandoning the present shoreline, but we can’t totally prevent it at some time in the future.”

“Vancouver, in Canada, is the most highly exposed area for sea level rise. It’s where the risk is greatest.”

2. The Tantramar Marsh in New Brunswick

In the 17th century, Acadian settlers in the Maritimes built aboiteaux, earth dams designed to keep the tides out of marshland and turn it into productive farms. One area they settled was the Tantramar Marsh at the top of the Bay of Fundy, between modern-day Sackville, N.B. and Amherst, N.S.

If you’ve gone to or from Nova Scotia by road or rail, chances are you’ve gone though the marsh – the Trans-Canada Highway and the rail line cut a straight line across the flat land, protected by a dyke.

By the end of the century, however, the highway, the marsh (and much of the town of Sackville) may be permanently underwater. Humans may not have taken the land from the sea, in the long run; rather, we borrowed it for a while.

CLIMATE CENTRAL

“$45 billion of trade passes through that corridor,” Mount Allison University geography professor David Lieske warns. “Stuff from the port of Halifax passes through our region. It also includes rail, it includes tractor-trailer traffic and just people commuting between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and PEI too, because that corridor is all kind of interconnected.”

Possible solutions include raising the dykes, moving the highway and rail line to a much higher and more massive causeway, or moving the land transport links between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick well to the north, to higher ground.

With the right combination of conditions, storms would combine with higher sea levels and the Bay of Fundy’s enormous tides to create sudden, serious flooding, Lieske says.

“The Bay of Fundy has a high tidal range, one of the highest in the world. The problem comes when you have combinations of events – when you have a typical average high level and then you get stuff piled on top of it.”

Improving the existing dykes might deal with the problem in the medium term.

“You’d be looking at acquiring rural land and modifying the dykes, which would be an investment. That’s a scenario that could buy a window of time. But past a certain point, if you start adding four metres or five metres, you’d be looking at replanning that corridor.”

The land connections could be moved to higher ground, but that route would be longer and more indirect than the modern one.

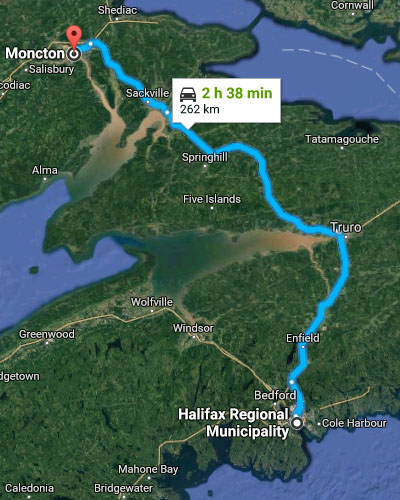

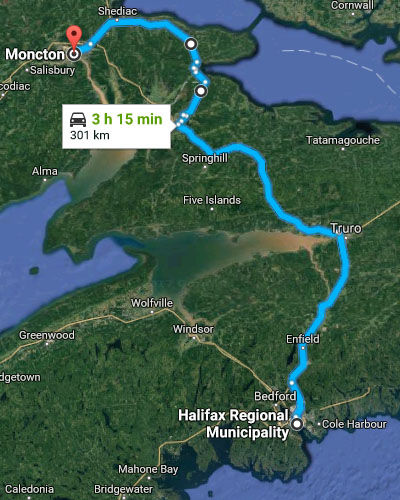

The first map shows a driving route from Moncton to Halifax today. It takes about two and a half hours.

A route around and above the marshes would add 39 kilometres and 37 minutes to the drive (assuming no new highways were built on new routes that don’t exist now.)

“Total abandonment would be something that would be done at the very end scenario,” Lieske says. “Let’s say you built a causeway, and you found that the cost of maintaining the causeway was unsustainable. So you might try an interim measure, and if flood levels and frequency proved to be so high, you might and up saying ‘We can’t even maintain the corridor.’”

“There may be a point where we realize that some solutions are untenable.”

Comments