For the 30 per cent of Canadians who rent, the factors that go into determining the fluctuations in their monthly housing costs are key. On average, rent for two-bedroom apartments increased by two per cent in Canada’s 34 largest centres between 2015 and 2016, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), despite a slight increase in vacancy rates of 0.1 per cent.

As of October 2016, the average rate for a two-bedroom apartment in Canada in new and existing buildings was $995.

WATCH BELOW: Toronto proposes crackdown on Airbnb rentals

Of course, that price varied greatly from city to city. The biggest rent increase was seen in Vancouver — a rise of roughly 5.7 per cent over the previous year — and is attributed to a limited supply of apartments and high turnover rate. Toronto was next on the list, with a 3.1 per cent increase. The average rental rates in Toronto and Vancouver for a purpose-built apartment building are $1,300 and $1,450 per month respectively; those rates are higher for condos, reaching nearly $2,000 in Toronto and $1,800 in Vancouver.

By contrast, Calgary saw a 7.5 per cent decrease due to its high vacancy rate (seven per cent).

“The number of vacancies in a city depends on the supply-and-demand equation, where low vacancies and competition lead to faster growth,” says Anthony Passarelli, senior market analyst at CMHC. “It’s also a matter of local economy and the incomes of the households in those areas. A good example of that is the oil-producing regions of the country. Rents in Calgary decreased on average because of the employment situation of many residents — a lot of people lost their jobs and they may have left the city, leading to higher vacancies.”

LISTEN: Marilisa Racco and AM640’s Tasha Kheiriddin discuss the rental market

Other factors that go into determining rental rates include the number of immigrants who arrive in any given area in a year, since trends indicate that the vast majority of immigrants live in rental housing when they first come to Canada. Data shows that net international migration in Canada was far greater between October 2015 and June 2016 than it was for the entire year from 2014 to 2015.

READ MORE: How much does a week of groceries cost in Canada? We crunched the numbers

As well, the aging boomer population means more people are selling their homes and downsizing to rental apartments. In Montreal, for example, an aging population that’s growing more rapidly than the national average offset the growth in purpose-built rental housing.

“In some metropolitan areas, like Saguenay and Trois Rivieres, where there’s a minimum population but the rents are still low, household income matters because the rents are related to them. But at the same time, if you have a low number of rentals, the rents will grow regardless, and they could become out of line with household income,” Passarelli says.

For a snapshot of what $1,500 in monthly rent (give or take a few hundred) will get you in several cities across Canada, Global News looked to Craigslist. Here’s what we found for the week Oct. 30.

Get weekly money news

Montreal

Monthly rent: $1,500 for a two-bedroom, one-bathroom condo

Area: Golden Mile

Calgary

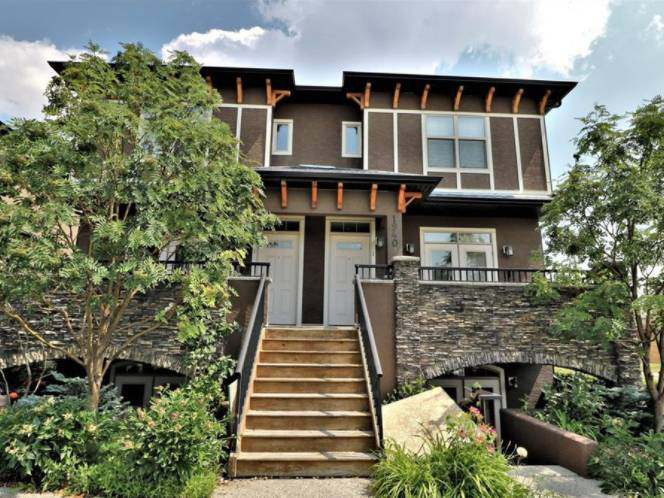

Monthly rent: $1,500 for a two-bedroom, two-and-a-half-bathroom townhouse

Area: Killarney

Edmonton

Monthly rent: $1,500 for a two-bedroom, two-bathroom condo

Area: Oliver

Halifax

Monthly rent: $1,600 for a two-bedroom, one-bathroom flat

Area: Downtown

Vancouver

Monthly rent: $1,950 for a one-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment

Area: Midtown

Toronto

Monthly rent: $1,800 for a furnished one-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment

Area: Annex

In addition to being at the mercy of fluctuating rental rates, renters are also proven to be more food insecure than homeowners. According to the latest available data from Statistics Canada, which date back to 2012, 26.1 per cent of households renting their accommodation experienced food insecurity versus 6.4 per cent of homeowners.

“We see to own a home is to be protected against food insecurity, even after adjusting for income and education,” says Valerie Tarasuk, professor of nutritional sciences at the University of Toronto. “It looks like people who own their home have an asset, so if something happens, like they lose their job or encounter an unexpected expenditure, they’ve got an asset they can borrow against. A homeowner can remortgage their home, they can get credit just by being a homeowner, and in the worst case scenario, they can sell. It acts as a significant financial cushion.”

Renters across the country tend to fit a profile: they’re younger, have a lower income and fewer professional jobs. Although Tarasuk says there are obvious exceptions. In Toronto, for example, that wouldn’t be the typical description of a condo renter.

READ MORE: Are you earning a middle-class income? Here’s what it takes in Canada, based on where you live

Tarasuk does point out, however, that homeowners are not immune to food insecurity. Many are highly mortgaged and are in deep debt, and those who own a home in a rural area don’t have the possibility of cashing in on high resale value.

“A lot of people think the solution is more subsidized housing, but the 2010 Survey of Household Spending found more than half of those living in subsidized housing were food insecure. Part of that is because their income is too low. Rent in subsidized housing is fixed at 30 per cent of their income, but that doesn’t leave enough money for other necessities,” she says. “They’re in a situation where they’re garnering the benefit of secure housing, but it’s an arbitrary percentage and there’s not much left over for food.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.