When people talk of athletes’ brains, they largely focus on the long-term effects of high-contact sports like hockey and football.

What’s less understood are the impacts on healthy, younger athletes in lower-contact sports like basketball, soccer and field hockey.

Coverage of concussions in football on Globalnews.ca:

It’s a gap that researchers at Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital and the University of Toronto’s MacIntosh Sport Medicine Clinic and have tried to fill with an academic paper in medical journal Frontiers of Neurology.

The study, titled “Structural, functional, and metabolic brain markers differentiate collision versus contact and non-contact athletes,” derived its conclusions from preseason MRIs on 65 university, or “varsity” athletes.

Get weekly health news

READ MORE: Brain of late B.C. Lions star Rick Klassen to be studied by concussion researchers

The research took account of their concussion history, or lack thereof.

- 23 subjects came from “collision sports,” which were defined as “routine, purposeful body-to-body contact” such as football and hockey

- 22 came from “contact sports,” which were defined as activities in which contact is permitted but not a key feature of competition, such as soccer and basketball.

- 20 came from “non-contact sports” such as volleyball

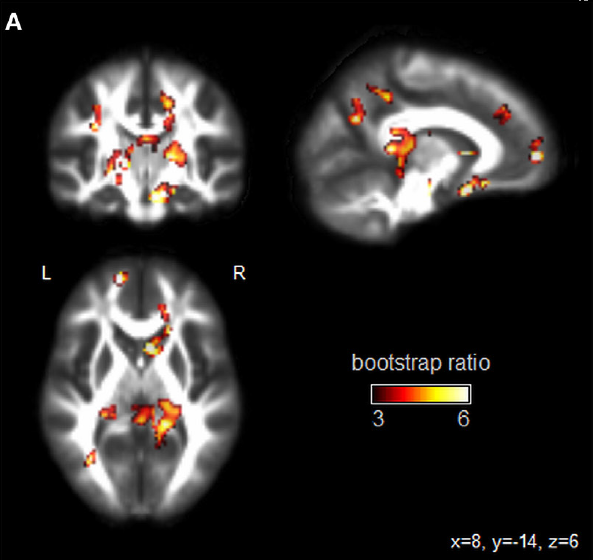

The authors found that collision and contact athletes showed “differences in brain structure, function and chemical markers typically associated with brain injury,” as compared to participants in non-contact sports.

They found differences in the structure of “white matter,” tissue that functions like threads and helps parts of the brain to communicate with each other, said a news release.

They also saw “reduced communication between brain areas and reduced activity” that were particularly pronounced in parts of the brain connected to “visual-motor function.”

“The functioning of these brain regions is critical for sport performance, as well as avoiding injury during competition,” the study said.

But these differences didn’t suggest “significantly impaired day-to-day functioning,” Tom Schweizer, head of St. Michael’s Hospital’s Neuroscience Research Program,” said in a news release.

The athletes who partook in the study were healthy, and didn’t report “significant health problems,” he added.

The authors noted a limitation, however: a number of different sports were combined into collision and contact activities, and the actual contact between them can vary.

Additionally, the impacts that athletes in these sports face can also depend on which positions they play and their teams’ playing styles.

And while scans were performed before varsity seasons began, these same athletes have also taken part in offseason sports, which might have exposed them to “repetitive head impacts.”

Nevertheless, “these findings provide important information about how MRI markers of brain health and concussion vary across athlete cohorts, improving our ability to model accurately the long-term effects of brain injury and repetitive impacts in sport,” the study said.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.