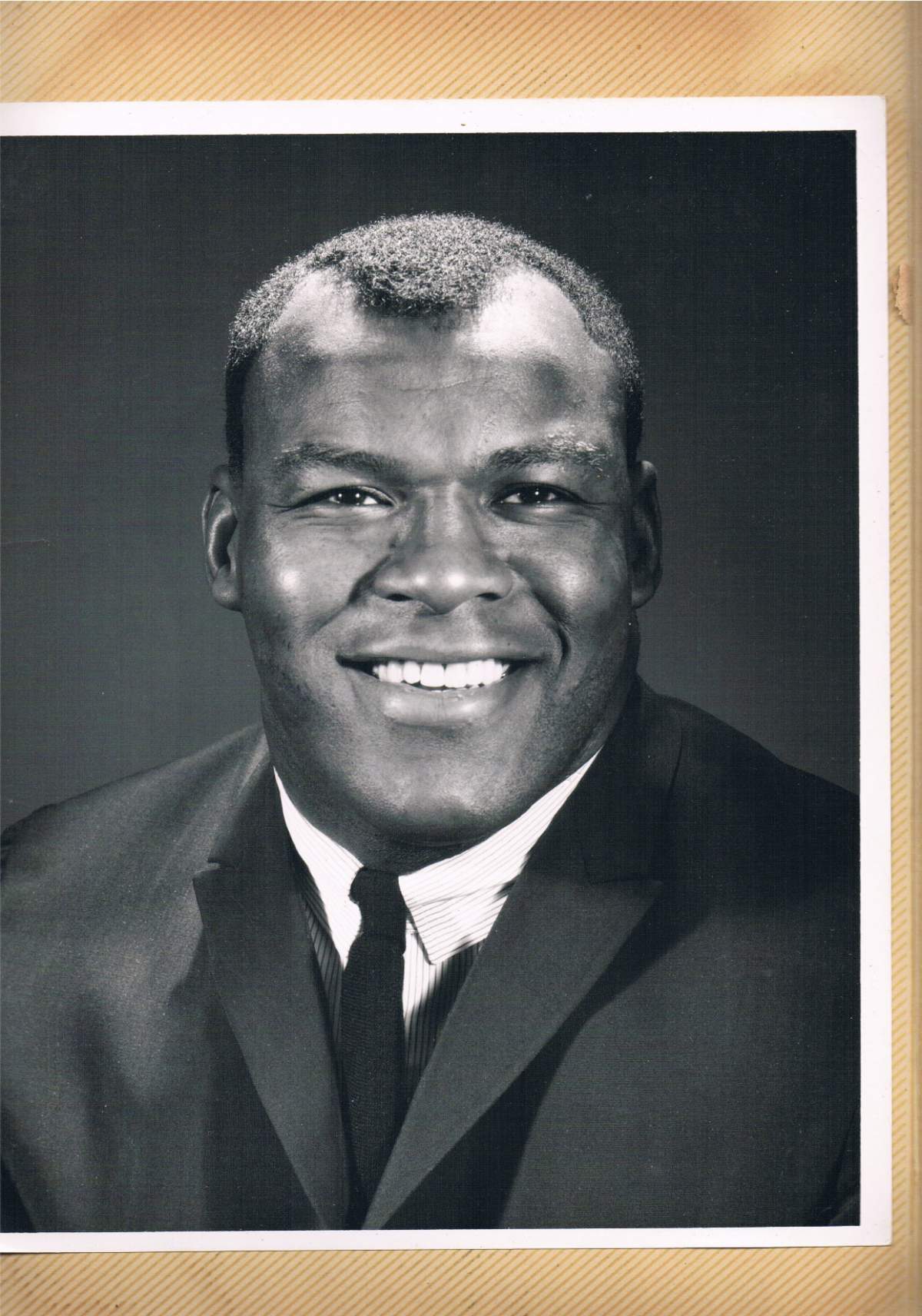

After years of becoming increasingly frustrated with his father, Scott Gilchrist now has a profoundly different understanding of the man many football fans remember fondly as “Cookie.”

Cookie Gilchrist played for three Canadian Football League (CFL) teams, including the Toronto Argonauts, Saskatchewan Roughriders and the Hamilton Tiger-Cats.

He also played in the American Football League (AFL), prior to the merger that would pave the way for the National Football League (NFL) as it exists today.

VIDEO: NFL exec admits link between football, brain disease CTE

The older Gilchrist was one of eight former CFL players included in a study of deceased football players’ brains. The report honed in on the link between playing football and CTE, and found evidence of the devastating disease in nearly all of the samples from the athletes. “Cookie” was diagnosed with the neurodegenerative disease.

Get weekly health news

“If only I had known then what I know now, I would have treated him different,” his son Scott said. “I came away with the thought that I could have had a better father, but I could have been a better son.”

CTE is often found in individuals who have been exposed to repeated head trauma, but it can only be diagnosed after death.

READ MORE: Scientists found CTE in 99 per cent of donated NFL player brains

For families faced with loved ones who appear to be showing signs or symptoms, it is a significant source of stress and confusion.

“The inability to let go on subject matters, recording of conversations — that frustration level where my brother and I both would say, ‘We just don’t get it,'” he recalled during an interview with Global News.

Scott, 56, now has a better understanding than most of what his father endured. A few years ago, he fell nearly 40 feet from a ladder at his Toronto-area home.

“Having my own empirical evidence of traumatic brain injury really drove the point home, where people get fixated on some things, where they can’t let things go,” he said.

The study focused on 202 football players, whose brains were donated for research. Eighty-seven per cent (177 players) were diagnosed with CTE.

Seven of the eight CFL players included in the research were also diagnosed with the neurodegenerative disease. That includes Winnipeg Bluebombers defensive lineman Doug MacIver.

READ MORE: These are the 9 risk factors for dementia that you probably didn’t know about

“He was starting to forget a lot more,” recalled his daughter Alexandria. “They said if he actually lived longer, he would have been diagnosed as having dementia.”

MacIver was part of the Bombers’ 1984 Grey Cup championship team. He died in his late 50s.

“Is the reward at the end, worth going through your family at the end of your life, not knowing who you are? Or dying prematurely? For some people, it is… and I hope that people take away that this is a serious disease,” she said.

While the numbers in the study are significant, the authors say more research is needed to truly understand the scope of CTE.

“I think the fact that we’re reaching more people, that they’re understanding that there is a connection between head injury from football and this neurodegenerative disease is important,” said doctor Jesse Mez of the Boston University School of Medicine.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.