Canada’s waterways are being contaminated with tiny pieces of plastic, and it’s coming from our clothing.

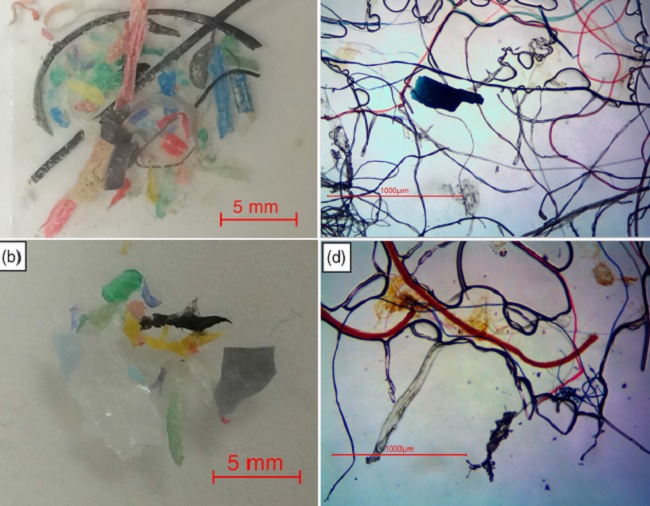

Those are the findings of recent research out of Carleton University, which found that the bulk of plastic fragments recovered from the Ottawa River and its tributaries were from microfibres.

READ MORE: Plastic in ocean could outweigh fish by 2050: report

“What really surprised us is that we found plastic particles in every single water and sediment sample we took, so the plastic was really prevalent in the river system,” said lead researcher Jesse Vermaire, assistant professor of environmental science, geography and environmental studies at Carleton University.

As much as 95 per cent of the plastic in the water samples collected by Vermaire and the Ottawa Riverkeepers was made up of microfibres. Around five per cent of the plastic was made up of micobeads.

“A lot of them are coming from synthetic clothing,” said Vermaire.

“If you wash a garment that’s made of synthetics — polyester or fleece or something like that — it releases hundreds to thousands of these microfibres every time you wash it.”

These tiny, light particles make their way into the water system through wastewater and even through the air.

There’s been a lot of talk about microbeads contaminating Canada’s waterways, and it even has led to the federal government issuing a total ban. All products containing the tiny contaminants will be off store shelves by July 1, 2019.

Get daily National news

Vermaire said more study is needed, but the fibres might be even worse than microbeads for the organisms eating them.

WATCH: Hunks of plastic found inside Fraser River steelhead

“They’re more likely to become all knotted together and stick in the gut of the organism longer. There’s worry that it might be more harmful but that needs to be sorted out more,” said Vermaire.

A 2015 study out of B.C. sounded the alarm over microplastics in water, and estimated that juvenile salmon in the Strait of Georgia may be ingesting two to seven microplastic particles per day, and returning adult salmon are ingesting up to 91 particles per day. That would mean a big marine animal like a humpback whale could ingest more than 300,000 microplastic particles per day.

Another study from the University of Regina found damage to fish stomachs caused by microplastics in “virtually all” fish examined.

WATCH: Microscopic plastic found in Wascana’s fish, water

What researchers do know is if the levels get really high — higher than the levels found in the Ottawa River samples — it can be fatal for the organisms living in and near the water.

“We know that animals are eating the plastic, that’s probably not good for them but we don’t know exactly when it starts to be really bad,” said Vermaire.

The next hurdle is finding a solution.

“It’s great that the industry and the government decided to phase out microbeads … it’s really microbeads that got people’s attention on this issue,” said Vermaire.

“But the fibres are way harder to control.”

Vermaire suggests further study on where the fibres are coming from, and to what extent the fibres are being consumed by organisms.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.