Breaking news brings out the fakers. And the Photoshop-ers.

This checklist (originally published here) proves its value over and over again.

This week’s terrorist attack in London was no exception. In the aftermath of a confusing violent incident, unscrupulous people with an agenda, pranksters and the well-meaning all throw things into the information soup.

READ: Fake news: Meet the alternate-reality version of the Quebec City shooting

Some are unsavoury, for example:

The Heartless Headscarf Woman Meme

The freelance photographer who took the photo, however, said the woman at right seemed shocked and was just trying to get out of the area. (Police were telling people to leave.)

“Looking back at the pictures now, she looks visibly distraught in both pictures in my opinion,” Jamie Lorriman told The Guardian.

READ: Fake news: Why does this simple Google search autosuggest a neo-Nazi site?

Keep calm and carry on

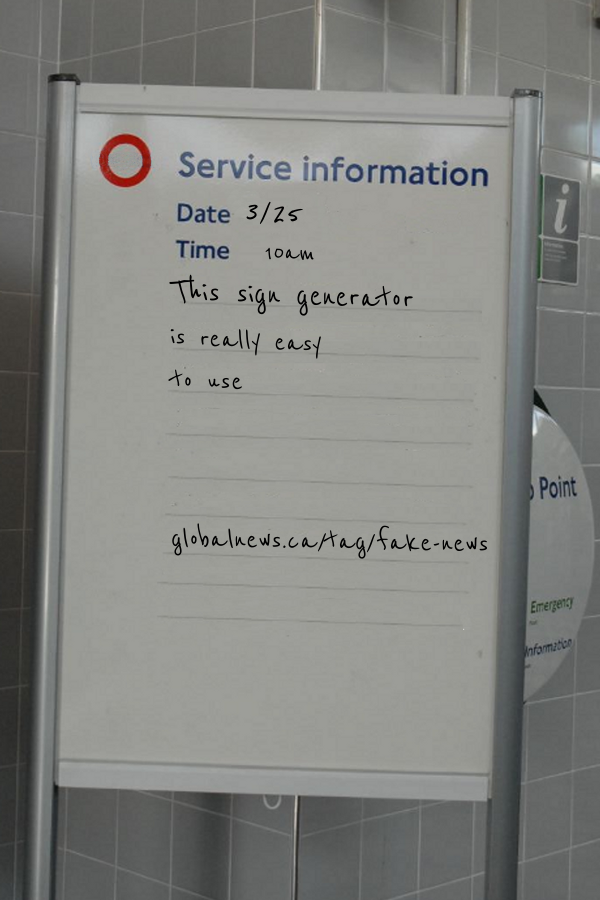

This one was more benign, but still fake. It purported to be a dry-erase board at a London tube station:

The BBC took it at face value, as did British Prime Minister Teresa May, who told the House of Commons that it was “a wonderful tribute” which “encapsulated everything everybody in this House has said today.”

Get daily National news

It was also a fake, made with the sign generator here. We’ve been playing with it, and you can too:

“Fake news and hoaxes routinely take advantage of plausibility,” the Washington Post explains. “Create a story or image that sounds or looks right to one particular viewpoint, and maybe it’ll be shared uncritically.”

READ: Fake news: No, strangers can’t find you on Facebook by taking pictures of you on the street

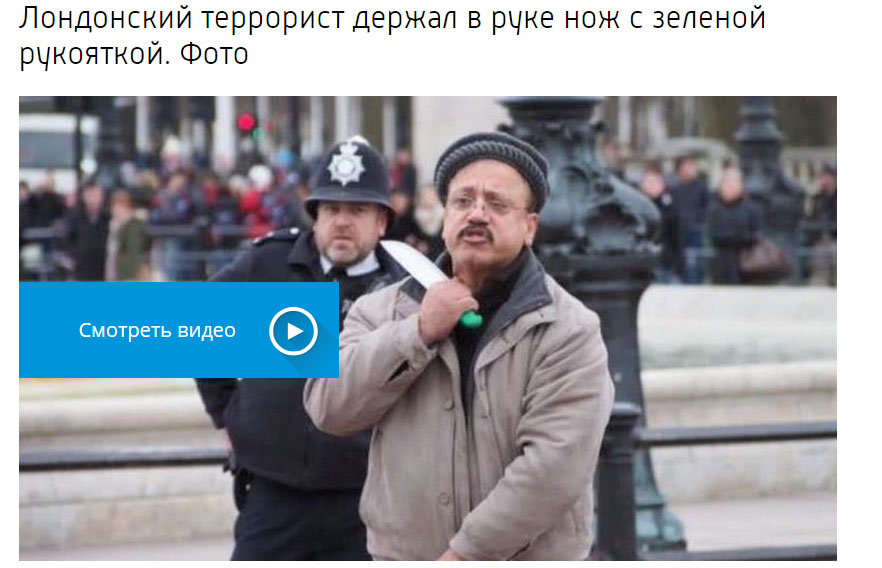

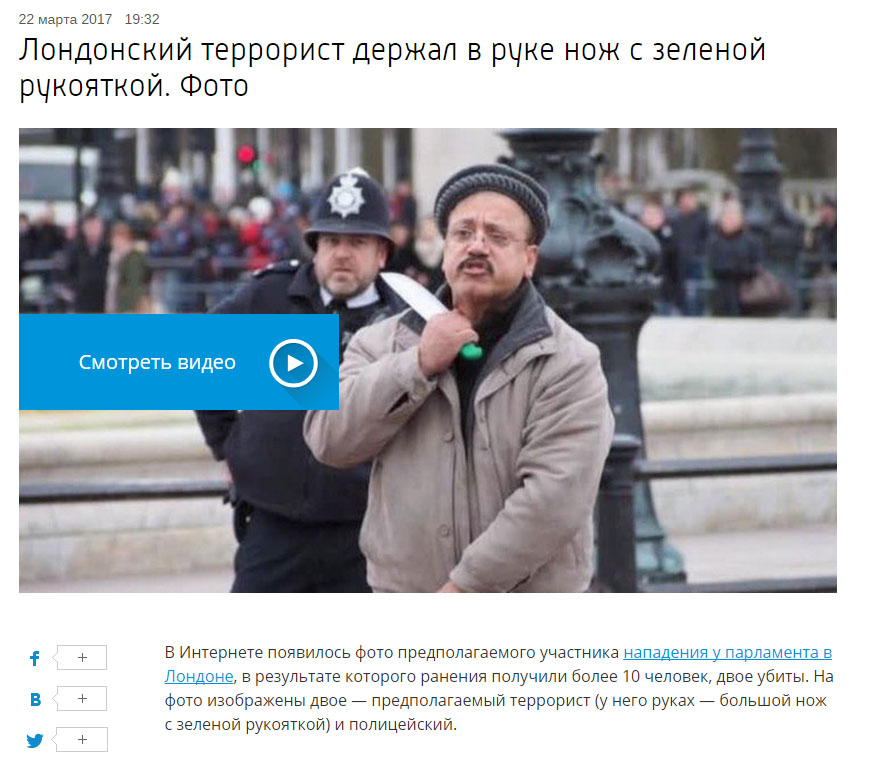

Guy with a knife? British cop? Vaguely Afghan hat? It’ll do

Wrong year, wrong person, wrong location (the image was of a man who waved two knives near Buckingham Palace in 2013, seemed to be mostly a danger to himself, and was Tasered.)

But it was good enough for several Russian news outlets:

And I would have gotten away with it if it hadn’t have been for you kids!

Can a resourceful band of Internet sleuths identify the London attacker within hours, by Googling stuff?

Uh, no. Radical Muslim cleric Abu Izzadeen, named online as the attacker, remains in a British prison, where he’s been since last year.

In fake news news this week:

- There’s no fake news on LinkedIn, asserts its executive editor, Daniel Roth. The reason seems to be that LinkedIn participants are in professional mode, and sharing fake news would damage their credibility.

- “The main factor in determining a reader’s trust in an article appears to be who shared it, not the news organization that published it,” a new study finds. The Nieman Lab explains.

- The FBI is investigating whether the right-wing Breitbart and Infowars sites were promoted during the U.S. election by Russian bots, the U.S. McClatchy newspaper chain reports. “Operatives for Russia appear to have strategically timed the computer commands … to blitz social media with links to the pro-Trump stories at times when the billionaire businessman was on the defensive in his race against Democrat Hillary Clinton … sources said.”

- Fake news, and the splintering of media into many silos micro-targeting different ideological groups, has the potential to damage society’s collective memory, a psychologist argues. Fake news in the present means fake memories in the future, which harms our ability to agree on basic facts across different political beliefs. “In the old days, there were corrective forces because really there were just a few information channels, and they were mostly trying to present valid news. Now there are channels that are not even pretending to do that. They’re trying to make money by getting people to click on them.”

- The Guardian takes Facebook’s tool for flagging fake news out for a test drive on the “Irish people were slaves too” story we discussed last week. At the moment, it only seems to work in the United States.

- U.S. Naval War College professor Tom Nichols argues that “…people have become overly critical of journalists for the same reason that they’re overly critical of government. They’re critical of journalists for giving them exactly what they want — stories tailored to them, pared down, pre-chewed and dressed up with pretty pictures — and then they say the media isn’t informing us enough.” His recently published book is called The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge and Why it Matters.

- Mother Jones talks to the Sleeping Giants, a group that lobbies companies to pull their ads from appearing on sites like Breitbart. (Because of the automated way online advertising is sold, they generally don’t know about it until it’s pointed out.)

Comments