The City of Edmonton has its sights on Mill Creek Ravine for a major water quality and erosion improvement project.

Water quality has long been a concern for the urban parkland as storm water runoff from the southeast industrial area, along with residential runoff from much of southeast Edmonton, flows untreated through the ravine and into the North Saskatchewan River.

“We have a requirement with Alberta Environment to meet a certain level of water quality that we discharge and also a requirement to continually improve the quality of what we discharge,” Kerri Robinson, a sustainable development engineer with the City of Edmonton, explained.

READ MORE: City looks to residents as it prepares to improve Mill Creek

Robinson said the city has done a lot of work with the industrial users to prevent pollutants from getting into Mill Creek.

“But there’s always improvements to be made, so what we are looking at are some ways to capture the sediment and hydrocarbons that are coming off all those areas, the roads and all those industrial areas before they get to the creek,” Robinson said.

Another issue plaguing the area is erosion. There are parts of the ravine that have been so severely eroded, trail closures are in place, cutting off access to the public.

READ MORE: Wet weather and erosion close some Edmonton trails

The concrete jungle of developed communities results in water running off surfaces to low-lying areas instead of absorbing into the ground. Since the mid 1900s, runoff from the Fulton Creek basin in east Edmonton has also been added to Mill Creek.

“The actual amount of runoff increases tremendously,” Robinson continued, “and that’s what we are seeing the impacts of.”

City planners are consulting with the public on three options, with a goal to better treat contaminated storm water and prevent erosion along the creek.

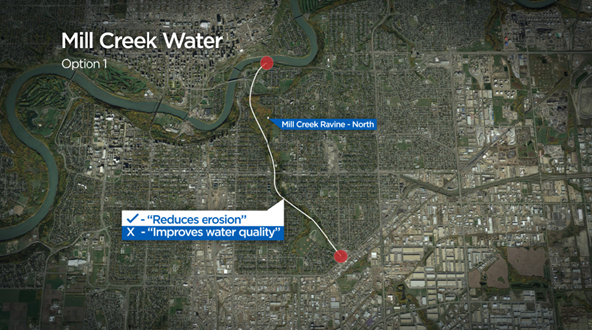

The most expensive option is to create a sewer tunnel to move excess storm water directly into the river. While this option will have the greatest impact on reducing erosion, allowing for the creek to flow at a more natural rate through regulation, it does not address the water quality issues.

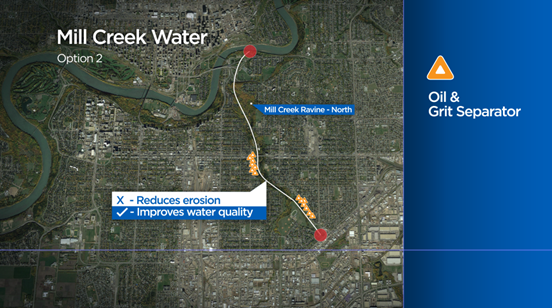

Option two would see oil and grit separators installed underground along storm water sewers throughout the southeast storm water basin. Though still in the early planning stages, the city estimates there could be up to 30 of them installed.

Get daily National news

While they would greatly reduce the amount of chemical toxins entering the creek, and eventually the North Saskatchewan River, on their own they would do nothing to prevent erosion.

The third option would see a familiar landscape in southeast Edmonton transformed into an urban wetland. As a means to naturally filter out contaminated water, a storm water pond would be created within the historic valley of the creek between Avenmore and Argyll near Argyll Road and 83 Street.

The city estimates this would offer the filtration power of two of the underground oil and grit separators, but would not have the capacity to prevent a major high stream flow event.

READ MORE: City of Edmonton looks at how to preserve Mill Creek trails

“We’re really putting this to the public because we know this area is highly used for other things,” Robinson said.

“So we’re looking for input from the public on what they’d prefer.”

An online survey is being conducted until Nov. 18 as Robinson’s team looks to gather feedback about the proposed creek improvement projects.

Meanwhile, other residents believe all that is needed is a cultural shift towards how we treat rain water right when it falls.

Alice Harkness is a Forest Heights resident and works with community groups like Keepers of Mill Creek on urban parkland sustainability.

Harkness believes the city’s formerly investigated low impact development options and increased educational programs within the Mill Creek and Fulton Creek basins would do the trick.

Low impact developments include creating rain gardens to capture more rainfall on private property, and creating more opportunities for rain water to naturally seep into the ground and eventually the water tables below rather than storm sewers.

“The money that would go into the connecting tunnel maybe could be given as grants for people to retrofit their areas,” Harkness said.

But the City’s latest report said that it would be too “difficult to implement” and that it “would require homeowners and businesses in the basin to buy in.”

“So that’s where I object and say, ‘we’ll push a little harder here,'” Harkness continued. “This is a really important and really critical issue.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.