It seems every few months, there’s a report somewhere about an asteroid that is about to pass “dangerously” close to Earth, one that might even impact our small planet, causing widespread devastation.

However, most of the time, the proximity of the asteroid is overblown, or just flat out incorrect.

READ MORE: WATCH: Possible asteroid explodes in Jupiter’s cloud tops

So how can you be sure that Earth won’t be decimated tomorrow by an asteroid?

You can’t.

Earth’s bombardment

Space is quite vast, with a lot of nothing in between various objects. However, there is a lot of space debris, or dust floating around out there. And, as Earth orbits the sun at 108,000 km/h or 30 km/s, some of that debris smashes through our atmosphere. Most often this translates into beautiful meteors that streak across the sky. However, there are larger pieces left over from the formation of our solar system. These could be comets — a collection of ice and dust — or asteroids, essentially hunks of rock orbiting the sun.

Every so often, however, an asteroid can get nudged by the gravitational effects of planets that put it in what could be a potentially hazardous path with Earth.

Each day Earth is bombarded with about 100 tons of space dust and small debris. And about once a year, a car-sized asteroid slams into our atmosphere creating a bolide, or extremely bright fireball. Most of the time, the bulk of the asteroid breaks up in our atmosphere, but every so often, some of it makes it to Earth, as was the case in Chelyabinsk, Russia, on February 15, 2013, an event where the airburst created ahead of the asteroid (also referred to as a meteor) injured about 1,000 people.

WATCH: Meteor crosses the Russian sky

While the idea that there are no guarantees we won’t be wiped off the planet by an asteroid may seem dire, the fact is that there are numerous space agencies — and some private ones — searching the enormous expanse of our sky, seeking out these potentially hazardous asteroids, or PHAs.

READ MORE: WATCH: Fireball lights up sky across northeastern U.S., parts of Canada

Interest in near-Earth asteroids has led to more funding at NASA (where it typically sees a shrinking budget), leading to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Near-Earth Object Program (NEO).

“The reality is that we now pretty much have a good understanding from the asteroid surveys where all the large asteroids that come too close to the Earth are,” said Peter Brown, professor at Western University’s Department of Physics and Astronomy. “We know that basically for the next 100 years none of those have any chance of hitting the Earth.”

Initially, the search for one-kilometre-wide — or larger — asteroids was fuelled by the belief that these would be the ones that would be catastrophic to Earth: if it fell in Antarctica, Brown said, repercussions would be felt around the world. But the news is good: we have found more than 90 per cent of those, according to Paul Chodas, manager of the Center for NEO studies (CNEOS).

Then there are the smaller pieces.

“We’ve got maybe 50 per cent of the 600-700 metre-sizes, but when you get down to the 140-metre size, you know, it’s obviously a very small fraction of the total,” Brown said. “So now instead of 1,000 objects we’ve got to find several tens of thousands.”

The search then began for even smaller asteroids, around 140 metres. These types of impacts would cause significant local damage, perhaps obliterating a city and affecting a province or state.

NEO was formed in 1998, shortly after Comet Shoemaker Levy 9 broke into several pieces and exploded in Jupiter’s cloud tops. Then there was the confirmation that an asteroid wiped out the dinosaurs.

“All of this wrapped together amped up interest in successfully finding anything that could be a danger,” said Chodas.

So what happens when we find one that could be a threat to Earth?

“We deflect it,” Chodas said.

While that might sound more like science fiction, NASA and countries around the world meet every two years to create scenarios. There is even an app where you can devise a plan to deflect an asteroid that measures 100 to 500 metres in diameter. And this isn’t a game: it’s a tool for those who can build a craft and create a plan.

Chodas also conducts exercises by the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and NASA’s Planetary Defense.

The most recent doomsday asteroid is Apophis (named after the Egyptian god of chaos). Initially, there was a small chance — 2.7 per cent — that this 320-kilometre-wide asteroid could impact Earth on April 13, 2029 (yes, it will be a Friday). However, further calculations (orbits are refined with extended observations) ruled out this possibility. It will definitely be a close pass, however, coming no closer than 31,000 km. For context, the average distance from Earth to the moon is about 380,000 km.

But the drama wasn’t over just yet.

There was a further chance that, should it pass within a particular region in space dubbed the “keyhole” which could alter its course, it could impact Earth when it passed us once again on April 13, 2036 (this time, a Sunday). But in 2013, NASA scientists concluded the chance of an impact was one in a million.

A history of impacts

In our planet’s early history — as in the early years of formation 4.6 billion years ago — we were bombarded by large leftover debris from the forming planets. Even today, it’s easy to see the scars left on our planet.

One of the most famous craters is Meteor Crater in Arizona (also known as Barringer Crater). It’s believed that a 40-metre asteroid slammed into Earth, creating what is now a tourist attraction.

In Canada, the most famous scar leftover from space debris is Manicouagan Crater in Quebec. The crater is about 215 million years old, created when a 5-kilometre-wide asteroid struck.

Keep yourself informed

Instead of falling prey to declarations that we could be wiped out by an asteroid tomorrow, make sure you read the claims with some skepticism and do some research yourself.

You can visit NASA’s Near-Earth Object page where they keep up-to-date on asteroids. Another valuable site is Spaceweather.com. You can scroll down the page to find some of the most recent asteroids that will make a close-encounter with Earth.

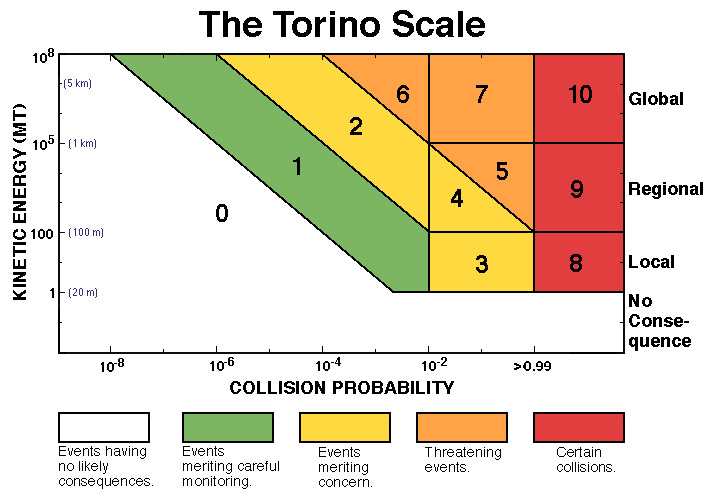

As for what’s out there and the risks to Earth, scientists have a scale to calculate such a thing. It’s called the Torino Impact Scale. Anything that is considered a close encounter ranges from a 2 to a 10. Two to seven would be considered concerning or threatening. However, no threat has ever gone higher than a one.

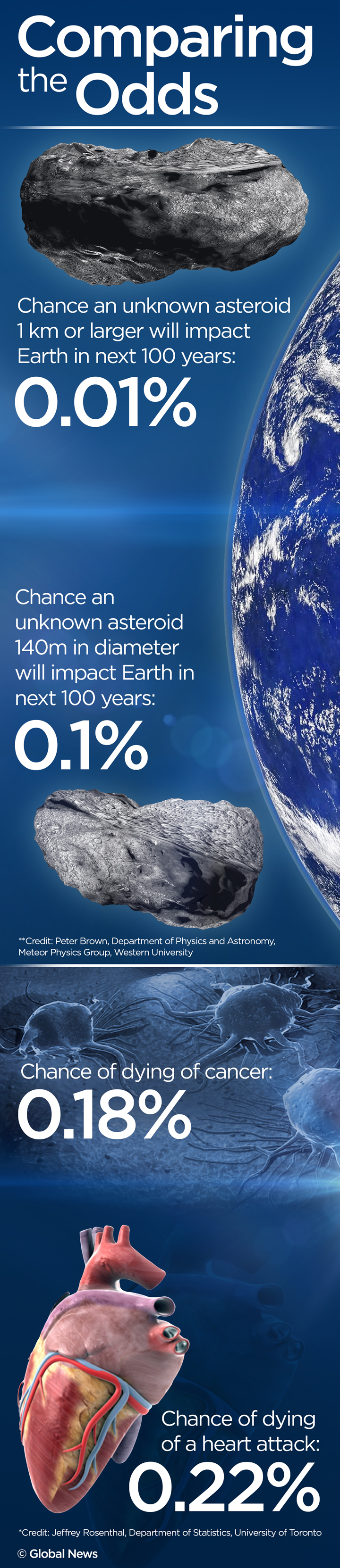

As for worrying about an Earth-destroying asteroid, Brown said that the chances of that happening are slim.

“I don’t lose any sleep over it,” Brown said. “And people really shouldn’t.”

Comments