Across British Columbia, there is a common thread to how our historical towns are maintained – or rather, for the most part, aren’t.

There is Barkerville and Fort Steele, heritage towns that have survived and become tourist attractions.

But much more common are the dozens of ex-towns spread throughout every region where virtually nothing remains.

In the Kootenays, on Vancouver Island, and around the central coast, communities cropped up everywhere there was a natural resource to exploit. When the resource dried up, the townsfolk left. Over the course of several decades, by flood or fire or looting – or just the natural passage of time – all remnants of the town disappeared save for a few scraps of wood and metal.

“I passionately believe in recognizing the people that built this province,” says T.W. Paterson, a historian and author on Vancouver Island.

“But it didn’t come free. It came at the cost of lives. We should do more to recognize that, our pioneers. And one of the best ways is if you could perceive something like a community.”

Paterson has tried getting the government to actively promote and preserve abandoned coal towns, to no avail.

“B.C. does a poor job of celebrating anything related to its past in terms of towns,” he says.

“Why do Barkerville and Fort Steele succeed? They go back to the gold mining era. The birth you could argue, the industrial birth of B.C. was the gold, and all of the excitement. Even today people get excited. Our most colourful part of our history goes back to the 1860s and the various stampedes.”

“Obviously everything requires a business plan. There has to be some attempt to cover costing. But it just doesn’t happen anymore. We have a government that is out to divest itself of its historic sites.”

Of course, preservation comes at a cost. In the middle of the 20th century, the provincial government spent considerable money to convert Barkerville and Fort Steele from struggling communities to heritage destinations. And while both are now privately operated, public funding is a key part of their business model: in 2010, they received an additional $8.7 million from the government.

So Paterson is skeptical any more sites in British Columbia will become funded tourist attractions. Not only is the money not there – there’s virtually nowhere left where there’s a population and infrastructure base to maintain the area.

“I’ll be damned if I know. Somebody has to live on site. You just can’t preserve anything that’s not attended,” says Paterson.

“It doesn’t change that we have a provincial government that they have no wish whatsoever to be involved with historic sites. Even if a ghost town would become available tomorrow, from a historic viewpoint, it probably wouldn’t happen.”

Which brings us to Sandon.

Get daily National news

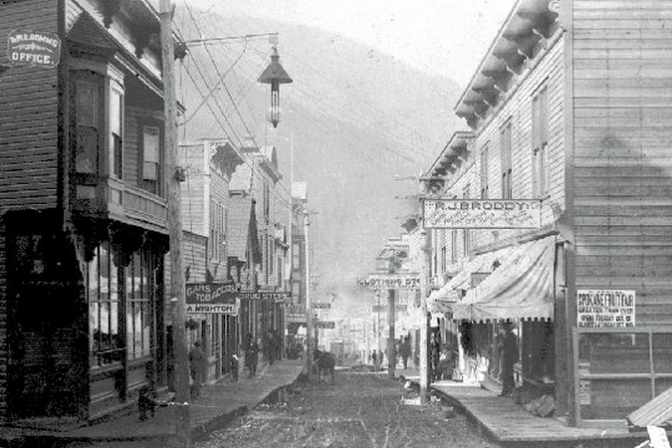

PHOTOS: Sandon as it existed in the late 1890s

Hal Wright is once again telling the story of Sandon and how he came to be its caretaker over 40 years ago.

“My mom’s family were here in the early years of Sandon, so there was family folklore that intrigued me. My great great uncle — who was still alive when I was a kid — his story inspired me. Friends and family helped me get my first job here when I was 15. I didn’t really plan to leave school, but I did and I never went back.”

In the 1890s, Sandon was one of the biggest towns in the Kootenays, the epicentre of the Slocan Valley’s silver boom. For much of the 20th century, the town slowly decayed. Workers left when the business model for the mines evaporated, and buildings and infrastructure destroyed by fires and floods were rarely restored.

But Wright has made Sandon his life’s passion, buying much of the vacant land from the government, and working with volunteers to preserve the remaining buildings (including the old city hall) and educate curious tourists who make the drive from New Denver or Kaslo, and pay by donation.

“We see many people coming, and their experiences are almost all great. You see things here you won’t see anywhere else in the world. It’s a place with a lot of appeal, and a place where a lot of great things happened.”

Sandon’s biggest tourist attraction to the thousands who come each year is, ironically, its fleet of heritage Brill buses shipped from Vancouver over a decade ago, still with original signage that reads out some of the city’s busiest streets.

“Of the 230 that were up for scrap, there were about 20 that were saved. We found homes for some of them in museums, as far away as Thunder Bay, but the vast bulk of them got scrapped. We were able to go and salvage many of the useful parts and components, which has helped us put these ones into reasonable shape.”

Ghost Town Mysteries: The old trolley buses of Sandon, B.C.

The most impressive artifact though is the power generating station. In a narrow valley, Sandon was the first fully electrified town in B.C., Today, the Silversmith Powerhouse, originally built in 1897, still provides electricity with machinery from the same era.

“It’s the oldest continuous producer in B.C, and it was also the first water power producer in Western Canada. The machinery in there is all original, and it does a fabulous job. It’s the only product produced in Sandon available for sale,” says Wright.

“All of this machinery predates the stereotypical powerhouse architecture. When people see the outside of the building, it’s not evocative of the big power plants that were built in the early 1900s, but when they see this, they’re stunned.”

On the surface, there appears to be the foundation of a heritage site that can last forever. But Wright says there’s a litany of reasons that hasn’t happened, from provincial cabinet ministers that supported Sandon going down to defeat, to BC Hydro paying what he says is less than top dollar for his electricity.

In the last decade, plans have been floated to turn Sandon into a regional park, or move the remaining buildings to a larger city in the Kootenays where they can be properly maintained. But without provincial funding, or agreement between regional governments and Wright, plans for Sandon’s future have stalled.

“Doing something like Barkerville was deemed to be too big by the province…as the provinces have run out of money, it’s been left on the shoulder of individuals to do that.”

“Where it goes in the future, a lot of it depends on markets and what visitors are willing to support,” says Wright.

Until then, Wright will continue to preserve Sandon’s past, and fight for its future.

“It seems like a shame for Sandon to completely disappear. That just hasn’t been acceptable to my family, and we’ve been doing everything we can to keep it alive.”

WATCH: Sandon as it exists today

“Ghost Town Mysteries” is a semi-regular online series exploring some of the strange sights from B.C.’s past.

The old trolley buses of Sandon

The swimming pool of Mount Sheer

The stolen lightbulbs of Anyox

The 30-year slumber of Kitsault

The international interest in Bradian

The cenotaph of Phoenix

Comments