An Emergency Trust Fund specifically for Canadian veterans in crisis has been depleted, Veterans Affairs confirmed Wednesday. Money, composed of donations from the public and held in trust by Veterans Affairs, was used to help those experiencing homelessness or distress.

In the fiscal year 2014-2015 approximately $200,000 was held in the account and this interruption could affect the help some homeless veterans will receive, putting more pressure on shelters and other emergency services.

READ MORE: Left behind: Watch the stories of Canada’s homeless veterans and the people who help them

“No homeless veteran will be turned away from Veterans Affairs,” a statement received by 16×9 reads, saying they will work with veterans to make sure their needs are met through other services and partnerships.

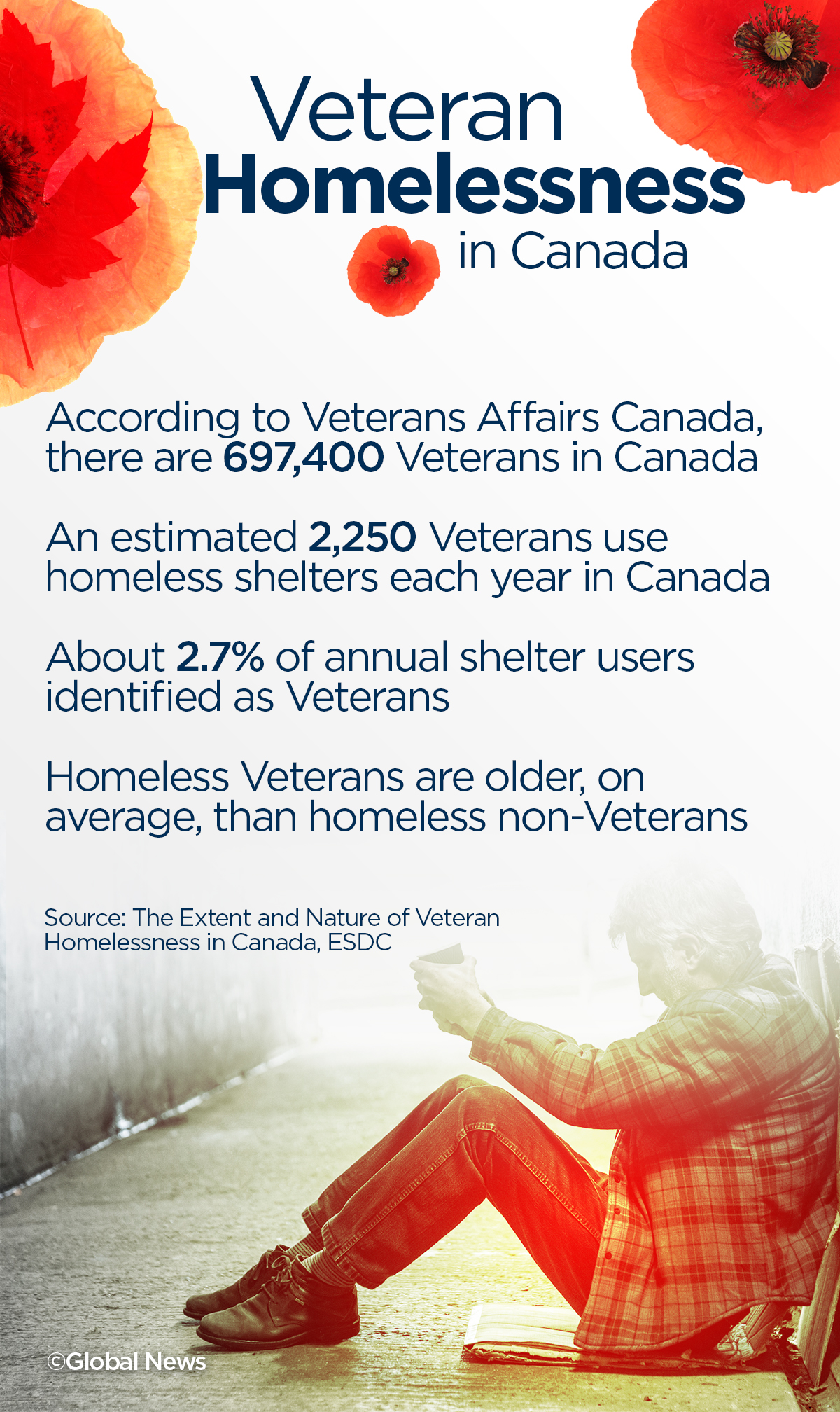

The struggles of homeless veterans started gaining attention over the last decade, as shelters, police agencies and academics started recognizing the unique population. Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) completed a report in 2015 estimating 2,250 veterans use homeless shelters every year. That number accounts for 2.7 per cent of annual shelter users.

16×9 has been investigating homeless veterans and wanted to know how that number compared to point-in-time counts in cities across Canada. Point-in-time counts measure the number of homeless people on a specific day.

The numbers we found were higher, ranging from 4.7 per cent to 18.3 per cent.

16×9 also met with many who live at The Madison, a home for homeless veterans in Calgary.

“For me, this place here, I feel like a millionaire,” said Gerald Zaleschuk, 71. Zaleschuk signed up for the Canadian Armed Forces in the 1960s as a teenager. He says he served 10 years.

“It made a better person out of you,” he said, describing himself as a “bad kid.”

After he got out of the military, he struggled with addiction, served time in prison, his marriage fell apart and he eventually ended up homeless. He says he lived on the street for almost 20 years, often camping in parks or sleeping on benches.

Get weekly health news

“It’s like you have a crisis in slow motion,” explains Cheryl Forchuk, assistant director at the Lawson Health Research Institute in London, ON.

She conducted some of the first research on homeless veterans in Canada.

READ MORE: Homelessness among veterans to be a top priority for Liberals: Hehr

“It’s a good decade often between the time they leave the service and the time they end up homeless.”

Forchuk says homelessness among veterans has many layers. Many like to avoid shelters, living off the radar and use their survival skills to camp in parks or ravines.

READ MORE: Is Ottawa underestimating the number of homeless vets?

Unlike some other homeless populations, there is not one event or crisis that propels a veteran into homelessness. She says it is often addiction or substance abuse that started in the military, coupled with depression or anxiety and challenges transitioning to civilian life that could contribute to the fall.

The Madison, open since 2012, operates on a “housing first” and “harm reduction” model. The primary purpose is to get veterans off the street, into safe and affordable housing. Residents are not required to attend counselling or addiction programs, though many do.

Fifteen vets live at The Madison, ranging in age from their 40s to their 70s. The only requirement is military service, with many of the men having served between the 1960s and the 1990s. Some were deployed overseas, others weren’t.

“These people want to congregate, they want to reconnect with their military culture. And they can’t do that in a homeless shelter,” says Forchuk.

Forchuk says military service does not cause homelessness, in fact time in the armed forces provides much needed structure and routine to some people. But once they leave and enter civilian life, that lack of structure and routine can cause many veterans to stumble.

“Just because you’re well thought of in the military, it doesn’t mean you’re employable on the outside,” says Peter Polley, another resident of the Madison. Polley served in the navy for 12 years, from 1968-1980.

Polley says problems need to be caught before they become unmanageable and more outreach is needed.

“Because, you’re fighting addiction. You’re fighting homelessness. Your health is down. All of these should be addressed before they become like I was,” Polley said.

Veterans like Zaleschuk and Polley look back on their time in the military with pride: a time when they were respected.

Veterans are also connected with Veterans Affairs case workers who can assist them in getting access to any benefits they may be entitled to. But in the case of many veterans, there are caveats and limitations to what they are eligible for, such as an injury linked to service or those who served in combat only. Homelessness is not considered an injury.

“We want to take a broad approach to this,” says Veterans Affairs Minister Kent Hehr. “I think our department has the capacity to do better”.

“This is something that is not only shocking to the Canadians it is concerning for me as minister. And I will say this, Veterans Affairs has never had it in its mandate to address homelessness,” Hehr said.

While Veterans Affairs do offer some benefits, charities and non-profit organizations, like local chapters of the Royal Canadian Legion, VETS Canada and the Poppy Fund, have stepped in to fill the gaps, providing supports, services and even assistance in locating homeless veterans.

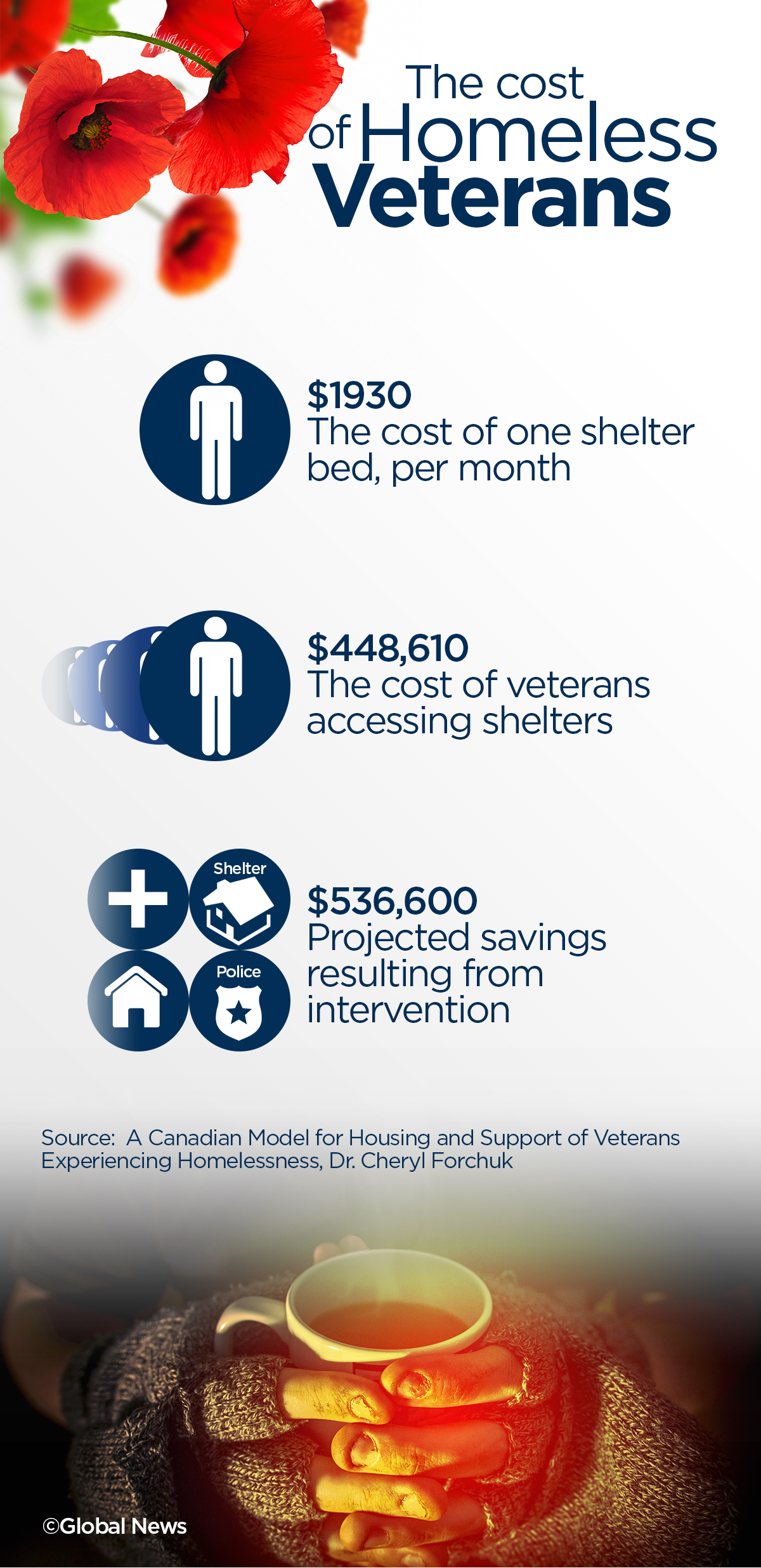

The Madison is operated by Alpha House, in large part with provincial funding. Forchuk’s research also shows that places like the Madison save money.

According to Forchuk’s research, it costs almost $2,000 to operate a shelter bed each month. Veterans cost the system over $88,000 in costs associated with accessing shelters and over $500,000 can be saved by intervening in homelessness.

The Emergency Trust Fund was established in 2010-11 and this is the first time it has been depleted. Veterans Affairs has called homeless veterans are a priority and announced a secretariat to investigate the issue. Minister Hehr hopes to present a framework addressing it within the next four months.

“They need more of these places,” says Zaleschuk, whose health is deteriorating. “If they didn’t get me into this place, then – I wouldn’t be alive today. I know that for a fact.”

16×9’s “Left Behind” airs Saturday, Apr. 23, 2016 at 7pm.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.