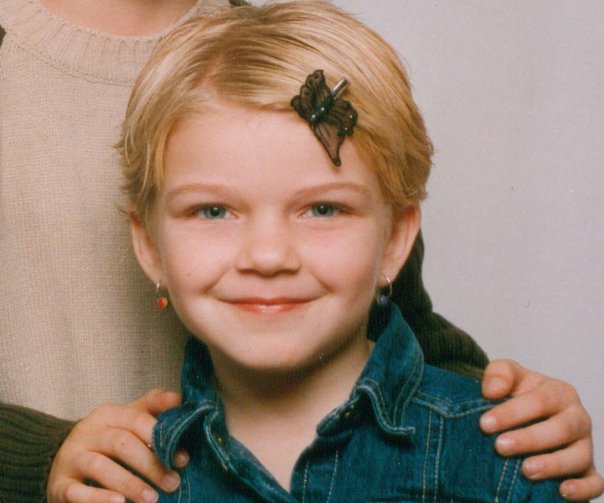

TORONTO – The tragic and horrific death of eight-year-old Victoria ‘Tori’ Stafford has caused many Canadians to question whether Canada should reinstate the death penalty.

On May 11, a jury of nine women and three men convicted Michael Rafferty of first-degree murder, sexual assault causing bodily harm and kidnapping in the death of the Grade 3 student.

Tori vanished outside her school in Woodstock, Ontario in April 2009. Her remains were found three months later under piles of rocks.

According to Amnesty International’s 2011 death penalty report, death sentences were pardoned or commuted in 33 countries, compared to just 19 in 2010.

Canada abolished the death penalty for murder in 1976. The last execution in Canada was at Toronto’s Don Jail on December 11, 1962.

In the wake of Rafferty’s trial, several petitions have been set up online urging the death penalty be reinstated for violent crimes against children. Outside the courtroom in London shortly after Rafferty’s verdict was handed down, motorists drove by yelling, “hang him.”

In 2010, Rafferty’s ex-girlfriend Terri-Lynne McClintic pleaded guilty to first-degree murder in Tori’s death and is currently serving a life sentence. During Rafferty’s trial, McClintic described the gruesome details of Tori’s kidnapping and death and testified that she killed the young girl using a hammer.

On Tuesday, Rafferty was formally sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years. He was also sentenced to 10 years to be served concurrently for sexual assault causing bodily harm and kidnapping.

Global News spoke with Aubrey Harris, co-ordinator of the Canadian Amnesty International Campaign to Abolish the Death Penalty about whether or not Canada should reinstate the death. penalty.

What is your definition of capital punishment or the death penalty?

Capital punishment, also called the death penalty, is the deliberate killing of someone (execution) as part of a sentence following a judicial procedure in response to an offence under the law. This can be differentiated from extrajudicial executions, which lack a judicial process (e.g., armed forces are sometimes accused of extrajudicial executions when executing prisoners of war without trial).

Why do you think such highly-publicized cases like the Rafferty trial cause Canadians to question whether the death penalty should be reinstated?

As with any violent description of a crime, it is quite normal for us to be angry and repulsed by the suggestion that a young person could have been treated in such a way. Public opinion polls taken at such times don’t usually ask what sort of justice system do you want to have, but whether it’s OK to execute someone convicted of a violent crime. These are really distinct questions. The distinction becomes clearer when presented with alternative punishments. Support for the death penalty plummets when given the option of life imprisonment, though death penalty proponents are unlikely to offer that when they claim to be seeking public opinion. The difference was also highlighted in the Abacus poll last year that claimed a majority support of the death penalty but also a majority of Canadians opposed to reinstatement.

There is another dimension to this question in Canada also – Canada cannot legally reinstate the death penalty without violating international law and destroying Canada’s trustworthiness for international treaties and agreements. It is also extremely unlikely that it could survive a Constitutional challenge today given that the grounds used in the Burns decision ten years ago have strengthened even more.

Today more than two thirds of the countries in the world have abandoned the death penalty in use or law. There is an international consensus that the death penalty is now a minority practice in the world with only a handful of countries regularly executing prisoners.

Get daily National news

Overall, do you think Canadians would like to see the death penalty reinstated? Why or why not?

The result of a reinstatement of the death penalty, even if it were legally possible, would be detrimental to Canada. Foreign relations would be grossly affected by the destruction of our reputation in trustworthiness, in the giant step backwards in human rights and the cost of implementing a death penalty system would put our domestic finances in peril. The cost of the death penalty has been cited as one of the driving forces behind the gradual abolition of the death penalty in the United States.

Fortunately I don’t think it would get to this point. Not only do the legal prohibitions make it unlikely, but public opinion generally moves against the death penalty once the population becomes more informed on the facts, in particular: it is costly, does not reduce crime and there is no way to guarantee an innocent person will not be executed.

Are there cases where the death penalty would be suitable? For example, in a case where a child is the murder victim or in a case where the jury concludes that, after examining all of the evidence, they believe that without a doubt the accused is guilty of first or second degree murder?

The death penalty corrupts justice. Sacrificing human rights to obtain a sense of vengeance is no way to achieve a just society. Even for the worst of crimes, the International Criminal Court, which hears the cases of those charged with crimes such as genocide, does not have the death penalty.

There is also an argument to be made that the most violent cases are also those where the greatest care must be taken over evidence. The pressure to find ‘the killer’ is going to be heaviest on the authorities and in some cases on the jury as well to convict. This is especially the case, for example, in the United States where many positions such as District Attorney or Sherriff are elected.

Amnesty International opposes the death penalty in all cases on the grounds that it is a violation of the most fundamental human rights: the right to life and the right to be free from cruel or inhumane treatment or punishment. These rights are enshrined in founding documents of the United Nations and are rights that were agreed to by all nations. Even the largest executing nations in the world acknowledge that there will be a day when they too will abolish the death penalty.

Advocates tend to argue that the death penalty acts as a deterrent for criminals yet some studies show that threat of execution is no more effective as a deterrent to murder than the punishment of life in jail. Why could that be?

Advocates making that claim have been proven wrong time and again. There have been countless studies on whether the death penalty acts as a deterrent. Nearly all come to the conclusion that the death penalty does not deter violent crime. The few that have made the claim that it does deter have all been shown to be seriously flawed. Some studies have even suggested that the death penalty may increase the rate of violent crime.

Part of the reason the death penalty does not reduce violent crime is that violent crime is not typically planned-out. The action is not a rational one and it is hard to expect that someone in the midst of irrational thinking would have the ability to stop and think rationally about consequences until after. Having the death penalty may also increase the risk of violent crime against authorities. Once a person has reason to fear being executed it is quite rational for them to do everything possible to avoid being caught.

There is a contradiction in the system when capital punishment is at play. Put simply, it is contradictory to say killing is wrong and to prove it, we are going to kill someone.

Does a death penalty sentence tend to provide more closure for families of murdered victims than a life in prison sentence?

No – there is no indication that a family actually gets “closure” through an execution. In fact there is a growing number of organizations in the United States and around the world, of survivors of violent crime and the families of victims of violent crime, that oppose the death penalty. Murder Victims Families for Human Rights is one such organization. In some cases also, because of the mandatory appeals processes built into the death penalty system, many families feel re-traumatized during each hearing. In the end family members are subjected to watching a human being be strapped down and killed. Afterwards the public often expects them to feel healed when in fact they have gained nothing.

In examining the question of closure, psychiatrists have come to the conclusion that witnessing an execution is highly traumatic and not healing. Dr. David Spiegel studied the witnesses of several high-profile executions in recent years and concluded “the theory that execution provides ‘closure’ is a ‘naïve, unfounded, pop psychology idea’ perpetuated by politicians and the media.”

I had the privilege of meeting and hearing the testimonies of several members of Murder Victims Families for Human Rights in 2010. One of the key points they made was that for healing to really work, they needed to be able to reach out and understand from the perpetrator why they did the crime. In many cases this would not be possible with a death penalty. Others noted that they felt that having someone executed was no way to honour the life of their loved one.

What are the consequences and benefits of reinstating the death penalty back into our society? Into our legal system?

There really is no benefit to reinstating the death penalty. There will be no reduction in the rate of violent crime, costs on the justice system will skyrocket and Canada’s international reputation will be ruined. We are bound by the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights not to reinstate the death penalty. There is no mechanism to withdraw from the protocol (unlike with the Kyoto Protocol).

We would not only be violating the protocol, but also the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. What state is likely to want to sign into any agreement with Canada when we have demonstrated our word is no good on such agreements? A treaty on arctic sovereignty? Forget it. Extraditing people from other countries for crimes they committed here? Not without diplomatic assurances that the death penalty will not be applied – but what value would those diplomatic assurances be with our ruined reputation for agreements? Trade agreements with European Union countries? Still no good.

Pleas with other countries not to execute Canadian citizens? On what grounds if we have decided that our government can have the ability to execute their citizens?

Should the debate regarding reinstating the death penalty be reopened? Should Canadians even care about this debate?

The death penalty cannot be reinstated in Canada. One day people will look back on the question of the death penalty the same way today we look back on slavery and wonder how we ever let it happen anywhere in the world.

There is still room for debate in Canada but the frame of the argument is wrong when we argue about whether to bring it back in Canada. We should be asking is Canada doing enough to help other countries advance their human rights. Canada was once a world leader in the abolition movement. This not only helped to protect citizens in other countries from facing execution, but also helped to protect Canadians.

Today there are at least six Canadians facing execution in other countries, many of whom face execution on incredibly weak cases and questionable charges. When we ask Iran not to execute Saeed Malekpour, sentenced to death for writing internet coding to allow photos to be uploaded, or with Saudi Arabia not to execute Mohamed Kohail, sentenced to death after he went to help his little brother get safely away from a crowd of armed youths at school, we argue most convincingly when we demonstrate that Canada opposes capital punishment always and are not just selective about whose justice system we recognize. We must argue from principle not by special request.

Comments