EDMONTON – When you run a ski hill, you tend to pay close attention to the forecast. And when you’ve been doing it for a long time, the long-term trends stand out.

The Sutherland family opened up the Rabbit Hill Ski Area in the mid-50s, and Jim Sutherland has owned the resort for 30 years.

“There’s less of these days where it’s really, really cold and nobody wants to ski,” Sutherland said when asked if he has noticed the effects of climate change specifically at his resort.

“We’ve definitely noted that our average opening date is about a week later than it has been in the past.”

His lift operations manager of 30 years, Bryan Wallace, agreed.

“For me, it’s not having the extreme cold in the mornings where we are questioning the wisdom of opening or not,” Wallace explained.

Like these two old friends, who don’t always agree on everything when it comes to the topic of our changing climate, many Canadians do not see eye to eye. In 2015, the Pew Research Centre found that 56 per cent of Canadians have noticed the harmful effects of climate change.

Get breaking National news

Observed records tell the climate change story through historical data, but finding meaningful information about specific areas in Alberta, like your own backyard, is a labour intensive process.

This is partly why Stefan Kienzle, a geography professor at the University of Lethbridge, created albertaclimaterecords.com.

“I wanted to find how much the climate has really changed,” Kienzle said, adding that he used only observed weather records from the past 60 years. His data includes no predicted forecasts, no computer projections – just information about how the weather was every day from 1950 – 2010.

Kielzle and his team then plotted the information in grids, focusing the data into plots of land about 10 kilometres wide. There are nearly 7,000 little squares that at the click of a mouse will show you how the climate in that area has changed on average each year.

The site currently has six parameters that can be searched: growing season days, heat wave days, days above 25°C, frost days, full days below 0°C and days below -25°C. Kienzle plans to increase the searchable information to include about 45 parameters in the near future.

So has Alberta’s climate changed all that much?

“In all of Alberta, the climate has warmed in all seasons. In the south it has warmed between one and two degrees, and in the north it has warmed by three and four degrees,” Kienzle explained.

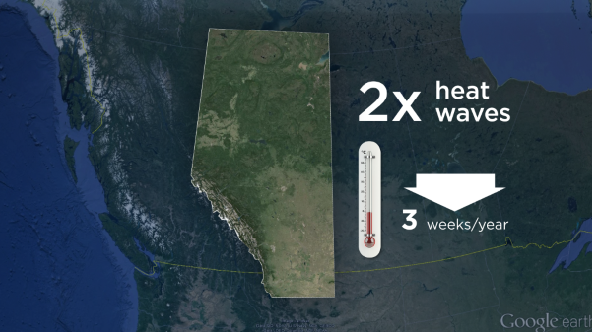

Also province-wide, heat waves have doubled and the number of full days below 0°C have decreased by three weeks per year.

Near Edmonton, average temperatures in the winter season have increased by five degrees each year. Near northern areas like the Caribou Wilderness Area and the Birch Mountains, average winter temperatures have increased by as much as 7°C.

The number of growing season days near Edmonton have increased by about two weeks per year, while areas near Grande Prairie have increased by three weeks per year.

It’s Kienzle’s hope that Albertans will use his tool to settle their climate change debates and change the conversation from “is it real?” to “how do we adapt?”

“It’s making important information available to decision makers, to planners, to farmers, and to the general public.”

Back at the ski hill, Wallace and Sutherland will continue their daily weather debates – one they say that they don’t always agree on. But there’s no argument that the need to adapt to “new” weather normals will be key to their future success.

“If it’s warmer, we may have the same level of business, but compressed into a shorter period,” said Wallace.

For Sutherland, embracing the newest snow-making technologies will ensure that his parcel of land, in a climate that has proved to be warmer than he’s ever seen, will continue to offer conditions ripe for his guests.

Comments