Over the past few months, people have captured footage of space debris burning up in our atmosphere. While certainly startling, the truth is, there’s been a lot of junk up there for a long time and so far no one has been hurt here on Earth.

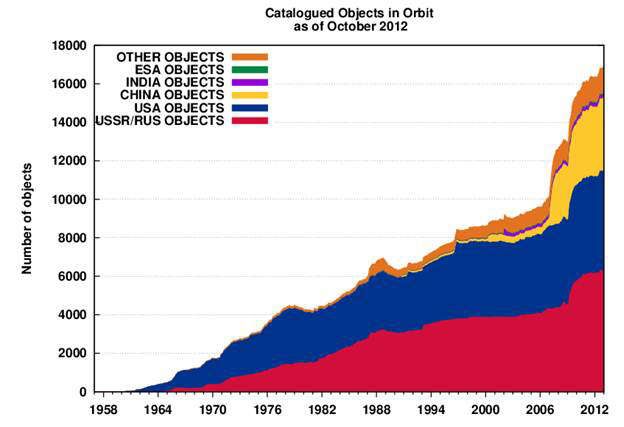

Since the first satellite went into orbit — the Soviet Union’s Sputnik, launched on Oct. 4, 1957 — we have steadily increased the amount of objects encircling our small planet.

READ MORE: WATCH: Space junk breaks up over Sri Lanka

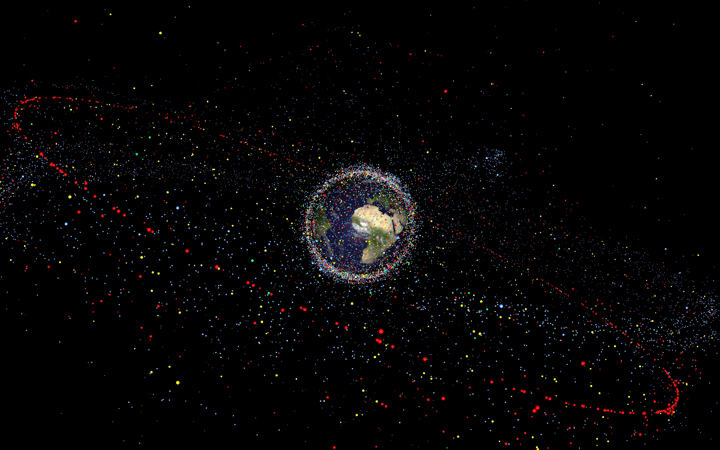

And it’s not just satellites. When speaking of space debris, agencies are specifically referring to inactive, human-made objects that orbit the Earth.

According to the European Space Agency (ESA), which estimates that there are about 23,000 objects from roughly 5,000 launches (as of 2012), about 65 per cent of the objects they have catalogued are as a result of 250 break-ups in orbit about 10 collisions.

WATCH: Space Debris: 1957-2015

Shockingly, most of those fragments came from a Chinese anti-satellite test that targeted the Feng Yun-1C weather satellite in 2007 which created more than 3,300 pieces of debris. In February 2009, an additional 2,200 fragments were created by the first accidental collision between two satellites, Iridium-33 and Kosmos-2251.

About 20 per cent of the objects are satellites (with fewer than 1/3 operational) and another 17 per cent are used rocket bodies and other objects from space missions. The remainder is debris from fragmentation.

According to ESA, if there is a collision at a speed of about 10 km/s in low-orbit by anything larger than 10 cm, it is considered “catastrophic.” And in space, catastrophic means the destruction of your spacecraft.

Collisions create something called the Kessler Syndrome where it becomes a cascading effect: debris creates more debris which creates more and on and on it goes. Anything larger than 1 cm can damage or destroy satellites. Millimetre-sized objects could disable the systems of a satellite.

Get daily National news

Aside from the ESA, other countries track debris as well, including the U.S. Strategic Command.

But every so often, in order to avoid collisions, space agencies will slightly adjust the positions of their satellites. But these thousands of pieces pose a risk to astronauts on a daily basis. Every so often NASA needs to readjust the station’s orbit in order to avoid debris.

When Canadian Chris Hadfield was on board the station in 2013, he noticed a small hole on one of the solar arrays.

Are we in danger?

Now, the big question is: How dangerous is this debris to us, down here on Earth?

ESA estimates that in all, about 75 per cent of large objects launched into space have already re-entered Earth’s atmosphere.

There’s something else that protects us from most space debris: our atmosphere. Anything that experiences a decay in orbit has to get through that first. You can think of it as our firewall.

READ MORE: Failed Russian space cargo ship to fall back to Earth, but where is unknown

“In the last 10 minutes before reaching the ground, the dense atmosphere starts to heat up and decelerate the object,” the ESA says. “In the case of very compact and massive satellites, and if a large amount of high melting-point material is involved such as stainless steel or titanium, fragments of the vehicle may reach the ground.”

However, it’s important to note that about 75 per cent of the Earth is covered in water and large parts of our land is uninhabited. So, “the risk for a single individual is several orders of magnitude smaller than commonly accepted risks in daily life,” the agency says.

In 2002, NASA estimated that the chances of being hit by space debris is 1 in 3,200.

That doesn’t mean nothing reaches terra firma.

Likely one of the most remembered space debris that impacted land was NASA’s Skylab in 1979.

The space station launched in 1973 and was operational until 1979 when it re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere. It was a public spectacle with people betting on where it would land. The San Francisco Chronicle even offered a $200,000 “reward” if a subscriber was hit by debris.

Ultimately, NASA adjusted its orbit to have it crash in South Africa. However, due to an error — and the fact that it didn’t burn up as quickly as they’d anticipated — the remaining debris crashed southeast of Perth, Australia (in fact, the Shire of Esperance fined NASA $400 for littering).

READ MORE: Russian spacecraft burns up over Pacific Ocean

But as we continually launch more and more into space, it’s clear that we can’t continue this process forever.

At the end of May, European organizations are gathering to discuss the mitigation and removal of space debris, which may help reduce any further risk to astronauts or inhabitants here on the ground, in case our luck runs out.

You can keep track of space debris yourself by visiting, Satview, a site that estimates the re-entry of various space debris.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.