It’s estimated that several million earthquakes occur each year, 300 in southwestern British Columbia alone. While some are strong enough to damage buildings, rattle shelves (and people), most go undetected.

That’s because — though we can’t see it or feel it most of the time — the ground we walk on is constantly moving.

READ MORE: Here’s a look at 5 of the largest earthquakes to strike B.C.

About 250 million years ago, Earth’s landmass was a giant super-continent called Pangaea. Then, about 200 million years ago, the land began to break apart. Then the plates drifted until they eventually joined and formed the continents as we know them today. There are eight large plates and nine smaller plates.

The plates are still connected and, because many are still moving (by millimetres a year, typically), sometimes they slip past one another, which we feel as earthquakes.

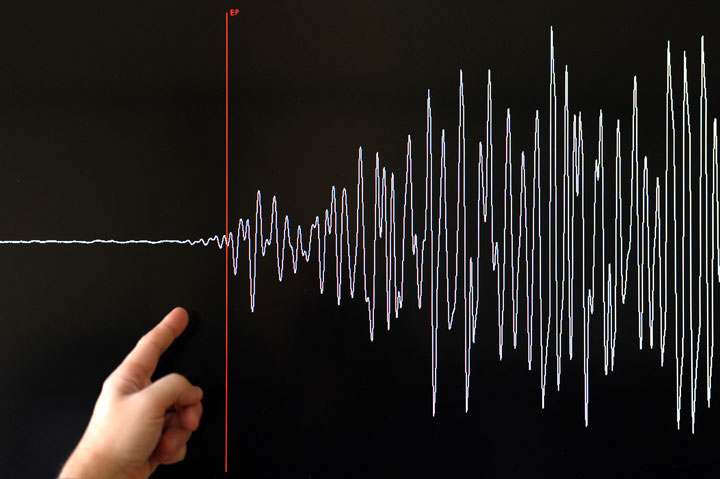

When measuring the magnitude of an earthquake — which ranges on a scale of 1 to 10 — it’s important to note that for every increase in magnitude, the energy released increases by about 32 times. A magnitude 8 earthquake is equivalent to about 6 million tons of TNT.

Get breaking National news

In the case of British Columbia, the Juan de Fuca plate is sliding beneath North America, part of the Cascadia subduction zone. This plate is moving towards North America by about two to five centimetres a year. Though the plate isn’t always moving it builds up pressure in Earth’s crust, which is responsible for about 300 earthquakes in the region each year. Seismologists believe that eventually the plates will snap loose and cause “the big one” — an earthquake in the magnitude of about 9.0. It’s believed that a major quake like that occurs every 250 to 850 years; the last major one happened on January 26, 1700.

WATCH: Report finds B.C. is unprepared for a major earthquake

Whether or not we feel them is dependent on its strength (magnitude), intensity, depth and even soil conditions.

Shallow earthquakes — those that occur from between 0 to 70 km deep — can be felt because the energy that is generated takes longer to distribute.

When seismologists talk about the intensity of earthquakes, they are referring to its effects. This is measured on the Modified Mercalli Scale which ranges from I to X (Roman numerals). The intensity varies on the type of rock or soil and how the energy waves travel through them.

The magnitude 4.3 earthquake that rattled residents on Vancouver Island on Wednesday occurred at a depth of 52 km and was a V on the Modified Mercalli Scale.

An example the U.S. Geological Survey uses to illustrate how this plays a factor is an earthquake that shook Mexico in 1985. The earthquake occurred about 300 km away from Mexico City, but the soil amplified the motion of the ground by a factor of about 75 times. Buildings 15 to 25 storeys high were damaged, causing 8,000 deaths and about $4 billion in damage.

There are still a lot of things seismologists are trying to better understand about earthquakes, and there is no way to predict when or where one may occur.

Comments