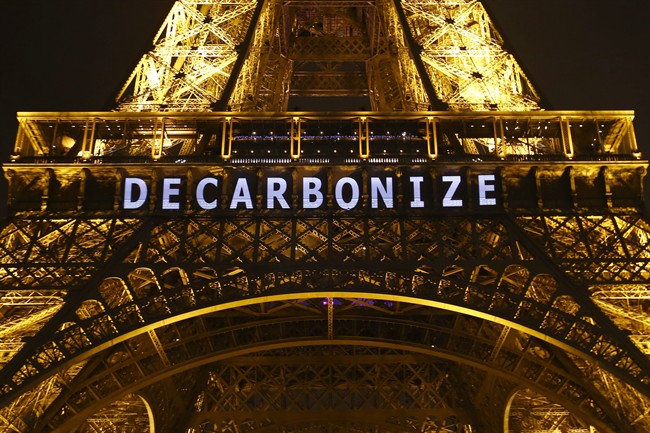

There was a lot of high-fiving and celebratory handshakes when the world’s countries reached that “historic” deal last weekend to fight climate change, but the harsh truth is that the ambitious goals of the deal are going to be hard to reach.

Of course, that doesn’t mean it’s not worth trying to achieve them, but the road to success is going to be a very difficult one to navigate in the years ahead (if the world can actually agree to stay on that road).

The “Paris agreement” commits countries to keep the rise in global temperatures by the year 2100 to below a further 1 C (temperatures have already risen by 1 C since the industrial age began). In practical terms, to reach that goal would mean a complete halt to all greenhouse gas emissions (from the burning of any oil, coal and gas) over the next 50 years, according to scientists.

READ MORE: How will the Paris climate change deal affect you?

While it may seem noble that 195 countries could actually agree on anything — let alone a plan that may theoretically “save the world” – the lofty goals they’ve reached consensus on are not necessarily entrenched in reality (despite that, it appears much of the environmental movement seems to think the deal should have gone much further, and therefore be even more unrealistic).

First of all, the countries agreed to “voluntarily” act to reach the new target, but there are no sanctions to be imposed on any country that throws in the towel and decides that weaning itself almost completely off of the use of oil or gas is simply too problematic a goal to strive for.

Second, while some jurisdictions — notably right here in B.C., home to a carbon tax — are indeed taking steps to slow down greenhouse gas emission levels, the fact is that many are not and will not anytime soon, even with the Paris agreement.

In the larger scheme of things, places like B.C. really don’t matter much in reaching any kind of world target. We simply aren’t a big player on the world stage (we contribute 0.1 per cent of the world’s GGEs), so even reaching the targets this government has set out may be a laudable goal, but it’s still almost irrelevant compared to the bigger problem.

READ MORE: What you need to know about the landmark Paris climate agreement

Unless places like China (28 per cent of the world’s emissions), the United States (16 per cent) India (six per cent), and Russia (six per cent) take drastic steps to curb their own GGEs, the accomplishments of less populated countries may count for nothing.

But China continues to burn coal (seen any pictures of the smog in Beijing recently?) in huge amounts, and they are consuming more natural gas than ever before. Russia’s own climate plan has been criticized for still allowing a 40 per cent increase in GGEs over the next 15 years.

And despite turning its back on the Keystone oil pipeline, the United States still remains very much wedded to its gas guzzling automobile culture.

We can debate, in this province, whether we should indeed raise our carbon tax (as the climate leadership team advocates) or not, but the reality is we’re just a little fish in a very large pond.

In fact, if other jurisdictions show little evidence of taking measurable, concrete steps in fighting climate change, raising the carbon tax in this province may become a non-starter for any of our politicians.

For now, Premier Christy Clark has taken the position that any increase in the carbon tax could only occur with a corresponding reduction in some other kind of tax. NDP leader John Horgan seems to favor Alberta’s approach, which is to take any new carbon tax revenues and invest them in renewable energy sources.

But if B.C. is seen as going it alone, I doubt either party leader will advocate a carbon tax increase as part of their next election campaign in 2017.

Now, this skepticism doesn’t mean throwing in the towel of course. But it does mean shedding some romantic notions arising from the Paris agreement, and recognizing how tough a job keeping temperatures down is going to be.

Keith Baldrey is chief political reporter for Global BC

Comments