TORONTO – Bottles, plastic bags, food wrappers and toys: they are all found in our oceans.

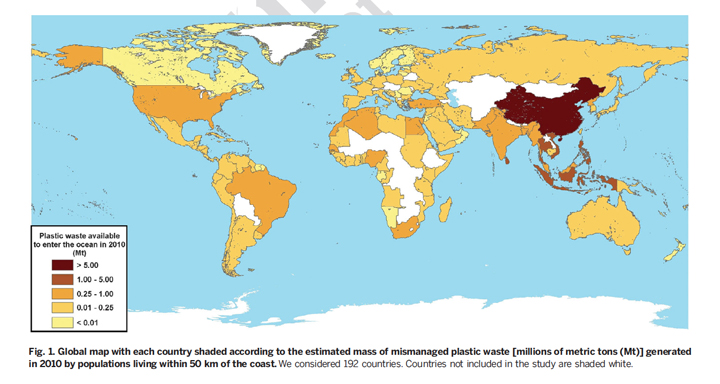

Though that’s no surprise, a new study that appears in the Feb. 13 journal Science, has concluded that between 4.8 million metric tons and 12.7 million metric tons of plastic generated from people living within 50 km of coastlines made its way into our oceans in 2010.

READ MORE: Why our oceans are choking on our garbage and how we can stop it

Taking the midpoint, that number is eight million metric tons, a number that is astounding to the researchers.

“Having sailed and measured floating plastics in both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, I expected the amount of plastic going into the ocean from land to be big. But the calculation is staggering,” Kara Lavender Law, co-author of the study and a research professor of oceanography at the Sea Education Association, said.

“Eight million metric tons. In a single year. That is the equivalent of five plastic grocery bags filled with waste for every foot of coastline around the world. Every year. “

The research studied countries with coastlines — 192 in all — and suggested that unmitigated, that number could soar to 155 million metric tons in the next 15 years.

According to the World Bank, the production of global plastic resin reached 288 million metric tons in 2012, a whopping 620 per cent increase since 1975.

A similar study headed by the 5 Gyres Institute calculated that there is more than 270,000 tons of plastic floating in our oceans. But there’s a big discrepancy between their study and this new one.

“Those estimates that you heard before is the standing stock,” said Jenna Jambeck from the University of Georgia, lead author of the study released Thursday. That means that the study examined only what was at the surface, not that which exists on the ocean floor.

However, Marcus Eriksen, an environmental scientist and research director of 5 Gyres Institute, disagrees with the study’s methodology.

Get daily National news

For one, though the study used data based on the amount of plastic generated per capita annually and the percentage of plastic not recycled, it only calculated the potential it had to enter the ocean.

READ MORE: Study finds more than 260,000 tons of plastic floating in the ocean

And for Eriksen, that was key.

“It was based of a per capita consumption and loss and waste management,” he said. “I don’t think that’s an accurate way to measure what’s in the ocean, by just looking at human behaviours on land.”

Specifically, Eriksen noted that in many parts of the world, such as Indonesia and Bali, they burn the waste in their front yards. In other parts, the waste is collected. So that waste doesn’t actually make its way to a dump and won’t make it into the oceans.

“Eight million tons going in,” said Eriksen. “I really think that’s far off.”

The 5 Gyres study took five years to complete. While Eriksen took part in 16 expeditions himself, the study also involved other contributors from around the world. A net collected plastics in swaths between three to five kilometres.

Eriksen said that it’s more often the small, non-recyclable, valueless plastic products that end up in the ocean.

Why so much plastic?

WATCH: 5 Gyres Institute examines plastic pollution in world’s oceans

When speaking to Peter Wells, adjunct professor at the Faculty of Science at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia about the 5 Gyres study in December, he agreed that people being unaware of the consequences of their actions is a problem.

Moving forward

But what to do about it? How can we remove microplastics without at the same time removing similarly-sized organisms and essential marine life? How can we collect the plastic from the ocean floor?

READ MORE: Sea turtles consuming record amounts of plastic, study finds

Collecting existing plastic may not be the way to go. Geyer believes the way forward is instead to modify our current practices.

“In some cases, redesign might be the best way forward,” he said.

Eriksen noted that in places like India and Indonesia, much plastic waste is collected — but only if it has value. Things such as straws, gum wrappers or stir sticks have no value, so they do make it onto the ground and into the ocean. So the key is assigning more value to plastic as an incentive for recovery.

Jambeck said that much attention is being given to the top 20 countries on the list.

“Behind these numbers are people,” she said. She stressed that it’s not about laying blame. “It’s not about finger-pointing.”

The U.S. is the one high-income country on the list. As for Canada — the country with the longest coastline in the world and a coastal population of roughly 12 million people — their study places us 110th on the list of 192 countries.

Evaluating how much plastic is in our oceans is of utmost concern for biodiversity — both on land and in the oceans. In particular, ingestion is of the highest concern for environmentalists and marine biologists around the world.

Stopping the plastic from reaching our oceans is key, said Law.

“This means investing in waste management infrastructure, especially in those countries with rapidly developing economies where increased consumption means accelerating rates of waste production,” she said. “In high income countries we also have a responsibility to reduce the amount of waste, especially plastic waste, that we produce. For example, each of us can use reusable instead of single-use items.”

“We need to work together on local and global initiatives… I’m optimistic this can happen.”

Eriksen noted that both studies are trying to achieve the same goal: awareness of plastic waste that ends up choking our oceans.

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.