TORONTO – In less than a year, we will be treated to a never-before-seen sight: the first close-up views of Pluto.

READ MORE: One year from now we will know some very cool things about Pluto

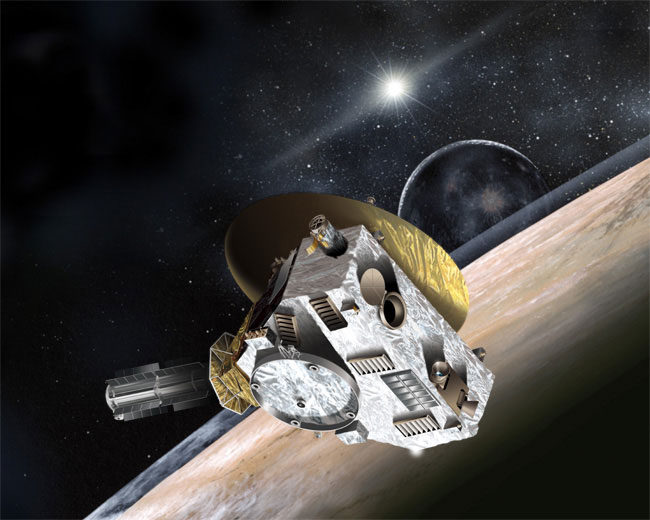

On Saturday, the New Horizons spacecraft, on its way to Pluto, answered a wake-up call. At 9:53 p.m. EST, operators at John Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) confirmed that it had entered its “active” mode. Though the signal moved at the speed of light (300,000 km/s), it took almost four-and-a-half hours to reach Earth.

New Horizons, about 5 billion km from Earth and roughly 261 million km from Pluto, has been put in hibernation mode more than 18 times. This was the final sleep for the far-flung probe.

“Technically, this was routine, since the wake-up was a procedure that we’d done many times before,” said Glen Fountain, New Horizons project manager at APL. “Symbolically, however, this is a big deal. It means the start of our pre-encounter operations.”

Why is this significant?

This is the first time that humans will get a close look at a planet since Voyager 2 passed Neptune in 1989.

By mid-May the probe will give us the best look at Pluto that we’ve ever had, better than the Hubble Space Telescope’s images.

There are also so many unanswered questions about Pluto. Though astronomers know that it is icy and has a thin atmosphere along with five moons, the actual surface of the dwarf planet is unknown.

Scientists also want to better understand what Pluto’s atmosphere is made of and how it behaves. There is even an instrument on board built by students called the Student Dust Counter, which measures the space dust that peppers the spacecraft during its trip across the solar system.

Get breaking National news

New Horizons was launched on Jan. 19, 2006, the same year Pluto was “demoted” from a planet to a dwarf planet by the International Astronomical Union. Still, the small, icy body has a special place in the hearts of many.

Dipak Srinivasan, an engineer for New Horizons said, “Regardless of its planetary status, it’s an important part of our solar system. Anything we can learn about our solar system can benefit us overall.”

Pluto — along with Eris, Makemake and Haumea — also belong to a group called Kuiper Belt Objects (KBO). The Kuiper Belt is a disc-shaped region in space that is home to many icy objects and is believed to be the original home of many comets.

“New Horizons is on a journey to a new class of planets we’ve never seen, in a place we’ve never been before,” said New Horizons Project Scientist Hal Weaver, of APL. “For decades we thought Pluto was this odd little body on the planetary outskirts; now we know it’s really a gateway to an entire region of new worlds in the Kuiper Belt, and New Horizons is going to provide the first close-up look at them.”

Unlike many planetary missions, New Horizons won’t stop to orbit Pluto. Because of the immense speed it needed to get to the farthest reaches of our solar system (Pluto lies about 5 billion km from Earth) the spacecraft had to reach an incredible speed — about 58,500 km/h. It is the fastest spacecraft to ever leave Earth’s orbit, and so it would take a lot of power to slow it down. So instead of loading the spacecraft with heavy propellant, New Horizons will conduct all of its imaging and scientific missions as it passes the 1,151 km-wide dwarf planet.

Its closest approach to Pluto will occur on July 14, 2015. But in the meantime the spacecraft will conduct other valuable scientific research beginning on Jan. 15, 2015. It will also study Pluto’s largest moon, Charon.

“We have all these assumptions on how things work. And that’s based on the data we have to date. Here is a sliver of our solar system, whether or not it’s a planet, who cares?” Srinivasan said. “It’s a sliver of our solar system that we don’t know anything about, that we have assumptions about. Once we actually get some real data, we’ll learn something… that’s why we do these things.”

“We’re on track for good things to happen in July.”

Comments