CARTAGENA, Colombia – More than 170 countries agreed Friday to accelerate adoption of a global ban on the export of hazardous wastes, including old electronics, to developing countries.

The environmental group Basel Action Network called the deal brokered by Switzerland and Indonesia a major breakthrough.

The deal seeks to ensure that developing countries no longer become dumping groups for toxic industrial waste such as old computers and obsolete ships laden with asbestos, said the group’s executive director, Jim Puckett.

Delegates at the U.N. environmental conference in Cartagena agreed the ban should take effect as soon as 17 more countries ratify an amendment to the so-called 1989 Basel Convention.

“This agreement was stalled for the past 15 years,” Colombia’s environment minister, Frank Pearl, said in praising the vote.

Katharina Kummer, the convention’s Swiss executive secretary, welcomed the vote. “I’m extremely happy,” she said.

Kummer estimated it will take about five years to reach the required 68 ratifying nations, but added: “It’s really hard to tell whether this will now generate more momentum for parties to ratify.”

Fifty-one nations have already ratified the 1995 amendment, which effectively enforces the Basel Convention, a treaty aimed at making nations manage their waste at home rather than send it overseas.

The United States, a top exporter of electronic waste, is among nations that have not even ratified the original convention.

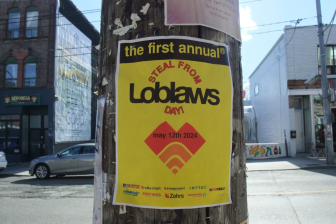

- Posters promoting ‘Steal From Loblaws Day’ are circulating. How did we get here?

- Canadian food banks are on the brink: ‘This is not a sustainable situation’

- Is home ownership only for the rich now? 80% say yes in new poll

- Investing tax refunds is low priority for Canadians amid high cost of living: poll

The global ban has been strongly backed by African countries, China and the European Union, which like Switzerland already prohibits toxic exports.

The issue took centre stage in 2006 when hundreds of tons of waste were dumped around the Ivory Coast’s main city of Abidjan, killing at least 10 people and sickening tens of thousands. The waste came from a tanker chartered by the Dutch commodities trading company Trafigura Beheer BV, which had contracted with a local company to dispose of the waste.

Puckett told The Associated Press there are no reliable estimates on how many tons of toxic waste are exported annually because developed nations don’t accurately report them.

He said a private U.S. company will, for example, list them as “exports” in sending them to a developing nation so they can avoid paying taxes and other fees.

The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal allows its 178 members to ban imports and requires exporters to gain consent before sending toxic materials abroad.

But critics say insufficient funds, widespread corruption and the absence of the United States as a participant have undermined the convention, leaving millions of poor people exposed to heavy metals, PCBs and other toxins.

They have long argued that an outright ban of exporting toxic waste is the only solution.

___

Associated Press writers Vivian Sequera and Frank Bajak in Bogota, Colombia, contributed to this report.

Comments