WATCH ABOVE: The WHO declared the Ebola outbreak in West Africa an international public health emergency that requires an extraordinary response to stop it spreading.

TORONTO – The Ebola outbreak in West Africa shouldn’t be a concern solely for the region. After months of battling the largest and longest outbreak of Ebola ever recorded, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the epidemic an international public health emergency.

With its declaration released Friday, the global authority is calling on health officials around the world to take on extraordinary measures in an attempt to stop the spread of Ebola.

READ MORE: Ontario hospital treating patient for Ebola-like symptoms

“I urge the international community to provide this support on the most urgent basis possible,” she said.

The declaration, which came after two days of discussion, is “a clear call for international solidarity,” but she acknowledged that many countries probably wouldn’t have any Ebola cases.

What could change with this declaration made?

WHO’s declaration holds significant weight, according to Canadian experts.

“It turns a local or regional issue such as Ebola in West Africa into a global priority. What it’s doing is telling the whole world to help to stop this virus,” Jason Tetro, a Canadian microbiologist and author, told Global News.

- Retired Quebec teacher buys winning lottery ticket at last minute, wins $40M

- N.B. election: Higgs went to ‘very dark place’ with Liberal joke, opponent says

- NDP want competition watchdog to probe potential rent-fixing by landlords

- Jasper mayor says CN Rail relocation will be devastating: ‘Deeply disappointed’

READ MORE: WHO declares Ebola outbreak a public health emergency

It hands countries the green light to move ahead with safety measures that wouldn’t normally be employed to contain an outbreak. In Sierra Leone and Liberia, for example, the military was called in to enforce isolation zones.

Hundreds of soldiers were deployed to quarantine villages, distribute food and medical supplies and provide assistance to health care personnel.

Read the WHO declaration and its recommendations for affected regions, regions at threat and other parts of the world here.

Countries around the world signed onto international health regulations doled out by WHO in 2005. These measures came in the wake of 2003’s SARS pandemic.

Under the WHO’s supervision, countries that signed on opened their lines of communication and notified the public health body if outbreaks were occurring. They also strengthened their public health system, allowed WHO is investigate when outbreaks occur and accept WHO recommendations, according to Dr. Michael Gardam, the director of infection prevention and control at University Health Network.

Get weekly health news

“The key word is recommendations. The WHO doesn’t have absolute authority in the world at the end of the day,” Gardam said.

READ MORE: Why the CDC declared the highest response level to Ebola outbreak

But its stance holds plenty of clout. And it’s only saved for the outbreaks the organization believes will be sticking around for awhile, with a lasting impact to the rest of the world.

“With this declaration, people are clearly putting a lot of resources into the cause and noticing what’s going on,” he explained.

A call for international response

A large part of the declaration is a call to action, not just in Africa but to countries that have the resources and can help.

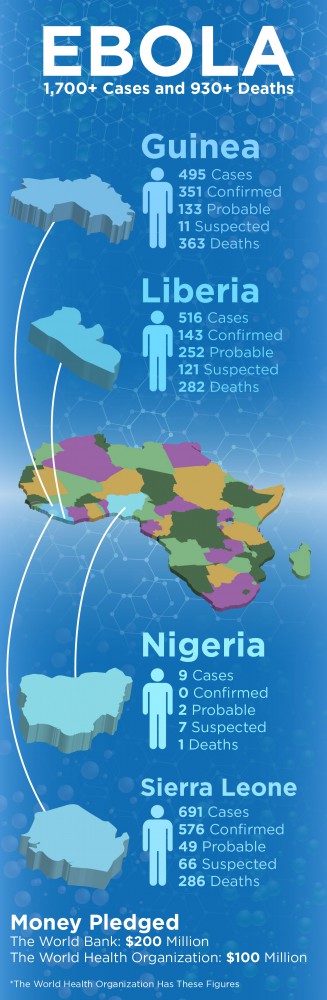

The World Bank this week pledged up to $200 million to fight the virus. The WHO is adding another $100 million to mark a “turning point,” according to its website.

READ MORE: ‘We’re setting a new path’ in fight against Ebola, Canadian aid worker says

That funding is going to be poured into infrastructure to build hospitals and clinics, increasing supplies such as gloves, gowns and masks, and paying frontline health care workers who are risking their lives to stifle the outbreak, Tetro said.

“What the declaration is doing is it’s giving affected people the opportunity to fight the outbreak using a global consortium,” he said.

It may be what aid workers and the organizations they represent have been calling for. In interviews with Global News, Médecins Sans Frontières doctors said their facilities in West Africa were at full capacity.

They said that what they needed most was assistance from WHO and other health bodies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (It ramped up its response to a Level 1 – the highest ranking reserved for the most severe health emergencies. In doing so, it freed up thousands of staff to shift their focus to the epidemic in Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea and, now, Nigeria.)

READ MORE: How Canadian docs are fighting Ebola during the world’s worst outbreak

“Declaring Ebola an international public health emergency shows how seriously WHO is taking the current outbreak, but statements won’t save lives,” Dr Bart Janssens, MSF’s director of operations, said in a statement.

“Now we need this statement to translate into immediate action on the ground. For weeks, MSF has been repeating that a massive medical, epidemiological and public health response is desperately needed to save lives and reverse the course of the epidemic. Lives are being lost because the response is too slow,” Janssens wrote.

MSF already has 66 international staff and about 600 local staff on the ground in three countries. It says it “simply cannot do more.”

READ MORE: Doctor with Ebola gives experimental serum to infected colleague

Tetro notes that if this hefty response occurred six months ago, the outbreak probably wouldn’t have grown to such proportions.

“These are countries that have severe problems socially, economically and politically. Only when it started to get out of hand did these countries have the obligation to put aside other humanitarian issues to start focusing on Ebola,” he said.

Missionaries are facing an uphill climb in West Africa – some local communities are certain it’s the aid workers that are bringing in the disease, that government conspiracy or witchcraft is at play and that if their loved ones go into clinic, they won’t come out alive.

“Before you guys came, we didn’t have it so you created this problem,” Canadian Dr. Marc Forget says he was told.

READ MORE: 5 things to know about the experimental Ebola drug

“It’s hostile…when that happens, it means people don’t want us to be there, they don’t understand what we’re doing and they care for their own family members and they’ll get contaminated in doing that,” he told Global News earlier this month.

Monitoring the home front

The declaration also hits home. Gardam, on Friday for example, had to clear his calendar and devote his time to liaising with hospitals, labs and clinics working through logistics and planning in case Ebola were to turn up within our borders.

“Everybody is starting to think about the possibility of having a case. The odds are slim but they’re never zero,” he said.

READ MORE: Why health officials say the Ebola epidemic won’t spread into Canada

But he’s resolute in ensuring the public: Canada’s health care system has strong protocols in place and public health officials learned their lessons from SARS in 2003.

Post-SARS, protocol for nurses, doctors and paramedics changed dramatically and surveillance is now in place brokering intelligence on rising diseases that could pose a threat.

READ MORE: SARS 10 years later – how has the health care system changed?

Patients are now screened for a fever, cough or trouble breathing. They’re asked a critical, telling question: have they recently returned from another country? Frontline health care workers assessing them don masks, gowns, gloves and any other equipment that acts as a safeguard.

Hospitals have better ventilation, single rooms, and plexiglass walls act as a barrier between emergency room front desks and sick patients.

There’s also compliance to advice doled out by health officials.

Tetro agrees. “Most of the implications that occur when you have a public health emergency are based on or parallel to what Canada already does on a day-to-day basis,” he said.

“Canada is a public leader in dealing with public health threats.”

More than 1,700 people have been sickened in the current outbreak in four countries. Nearly 1,000 people have died, according to WHO estimates.

carmen.chai@globalnews.ca

Follow @Carmen_Chai

Comments