TORONTO – From eBay and Craigslist to Airbnb and AutoShare, consumers are taking part in what’s being called the “sharing economy”—people using digital technology to provide and consume services in informal, non-business settings.

That’s how University of Toronto Rotman School of Management professor of marketing Avi Goldfarb defined it when speaking with Global News in May.

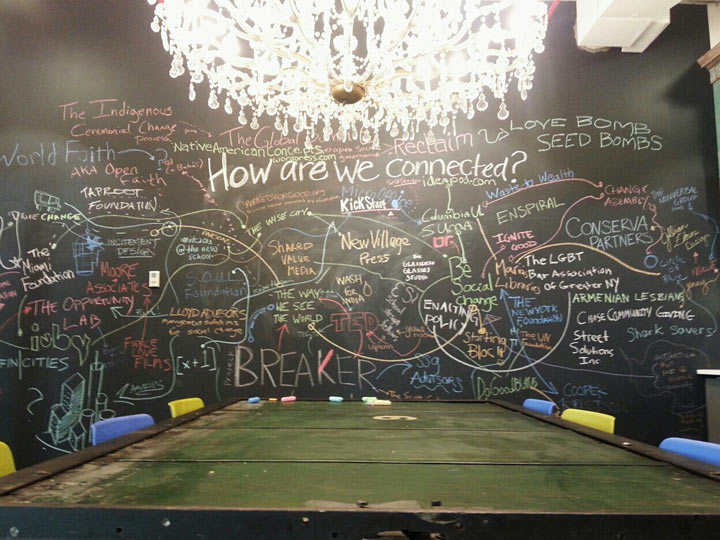

Adil Dhalla, the director of culture at Toronto’s Centre for Social Innovation (CSI), explained the trend as it’s being promoted at #ShareFestTO—a local event the CSI is hosting Wednesday night.

“I define the sharing economy as a social economic system in which people are more interested in access rather than ownership of goods, and accordingly are finding ways to share their services, their skills and their products rather than selling them.”

The event, taking place at the CSI, is an introduction to 30 such sharing organizations, including:

- Swapsity — a bartering site where you list items or skills you have to offer as well as a wish list of items and skills you want for yourself

- AutoShare — pay a membership to get access to cars for hourly rates below what you’d pay for a typical rental car or taxi

- The Toronto Tool Library — pay a membership to get access to power tools that you may only need to use once a year

Though many are well-known and increasingly used like Airbnb and eBay, Wednesday’s ShareFestTO event is meant to introduce people to some newer groups operating on a more local level.

Even though new sharing sites continue to pop up, Goldfarb pointed out some have been around for years.

“Canadians are avid eBay users, and in a way that’s the very first sharing economy company to the extent that people had stuff in their basement, and they put it online and other people bought it,” he said.

Ten years ago, the CSI was one of the first organizations to implement the sharing economy as the first co-working space in Canada, said Dhalla. He said the centre provides office space and services to “accelerate” the work of people who “specifically have some sort of mission around making the world a better place.”

When it comes to sharing economies providing access to services, Goldfarb said in a past interview we’re at a point where it’s hard to tell the good ideas from the bad, despite a movement toward one-off exchanges where people are verified through a reputation system.

“Having looked at all sorts of other similar industries where: okay here’s the Internet, here’s a new idea, there’s lots of possible businesses and massive entry…Some worked great, some didn’t,” he said in May. “We seem to be in the same kind of place now with the sharing economy.”

Get breaking National news

But some are skeptical of the idea that you can create a successful business based on sharing.

Marvin Ryder, McMaster University marketing and entrepreneurship assistant professor, said people who live in cities seem to be relatively affluent, and rather than borrowing, most would prefer to buy.

“Let’s say you need a staple gun. Chances are if you live in an apartment building, somebody has a staple gun. Are you going to go door-to-door knocking? The answer is likely no. Chances are you’ll go to the store and spend $10 on a staple gun because in the grand scheme of things $10 isn’t that much money anymore.”

Ryder acknowledges some sharing economy-based organizations may work well in high-density cities, but suggests Facebook is better at offering a space that facilitates sharing.

“Suppose you need something – you’re going to make jam this weekend and you need some jam jars,” he suggested. “Rather than buy them, you post on Facebook: ‘Has anyone got jars they can lend me?’ Your Facebook friends might rally.

“They might not be next door to you, but there are other ways to do sharing than going through some formal organization.”

But Dhalla believes the sharing economy idea is rapidly building momentum, with many success stories popping up.

He said as a concept, it emerged in the mid-2000s for two reasons. One was that technology enabled “rapid scaling of it as an industry” (here he pointed to laptops enabling co-working since people are no longer restricted to one work location).

The second was a greater societal desire to share rather than own.

Dhalla said the concept isn’t a sign we’re no longer willing to ask a neighbour to borrow sugar or a power tool; rather, sharing economies are creating happier communities.

“Sharing spaces like tool libraries, and like kitchen libraries and like libraries, are community hubs—and those are opportunities to go meet other people and trust them,” he said.

“I think the real fear with technology is that we all sit in front of our computers, and we’re all strangers to the people around us, whereas I think the sharing economy actually brings people together and fosters community-building.”

Some might argue that just because we don’t need to own stuff—as the CSI points out—doesn’t mean we don’t want to.

Dhalla acknowledges that it’s a paradigm shift that still needs to happen.

“The fact is we are running into some very well-known challenges for resources. The world overpopulates, and how do we all own these things? It’s not possible.”

He pointed to the recession as a catalyst for the growth of the sharing economy in the last few years. Of more than 20 local organizations taking part in the ShareFestTO event, Dhalla said 95 per cent of them didn’t exist two years ago.

He also highlighted Airbnb’s success in San Francisco as a sign people are using such sites for additional sources of income. A 2012 study commissioned by Airbnb suggested San Francisco users made an annual average of $9,300 for listing a home and $6,900 for listing a private room or shared space.

Rather than “everyday people,” Ryder suggested there’s a “chunk of society” who are hyper-green and engage in reducing, reusing and recycling instead of buying as almost a spiritual cause.

“But they are a relatively small percentage of the population and the rest just find other ways to share rather than go through these formal organizations,” he said.

But Dhalla doesn’t think it’s just a fad for a select group.

“I don’t think it’s a fad – it’s been happening for hundreds if not thousands of years. What’s happened now is we have the tools technology-wise and we have the density and urban space to actually make it legitimately scalable and sustainable.”

Visit the Centre for Social Innovation’s Annex location at 720 Bathurst St. Wednesday July 16, 6:30-9:30 p.m. for ShareFestTO.

Comments