Mark Peters, a third-generation Manitoba farmer, is staring out at his flooding fields.

“We’re just watching all the water go through the dike,” he says.

READ MORE: 5 photos from the Manitoba flood zone

His farm – 400 acres of hay land – runs right alongside the Portage Diversion that empties out into Lake Manitoba.

The historic flood of 2011 made it impossible for Peters to plant until last fall. This would be his first hay yield since then.

Now, he stands to lose it all. Again.

“It’s all under water again. So it’s going to be another three years of loss,” Peters said.

“I’m at the end of my rope.”

Peters also grows seed potatoes that he sells to growers. It looks like he’ll lose about 25 per cent of that crop, too.

“It’s just hard to take. They’re taking our livelihood away from us.”

“They” is the Manitoba government.

“I’m very disappointed in them. I don’t think they’re adequately looking after the waterways.”

Though Peters believes diversion – where water is diverted away from rivers that may overflow during heavy rain or spring runoff – is the problem, there’s more to it than that. And it’s a problem that plagues the entire Prairies, not just Manitoba.

The importance of wetlands

A wetland is an area of marshes and swamps and are one of the most important systems in our natural environment.

About 25 per cent of the world’s wetlands are found in Canada, most of it in the Prairies.

Get breaking National news

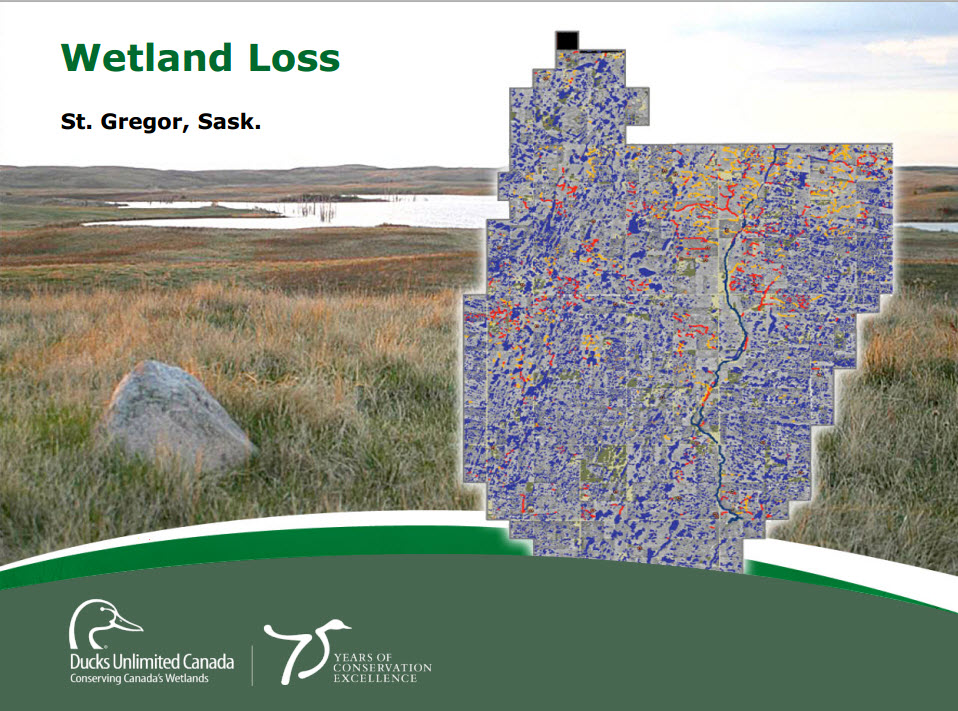

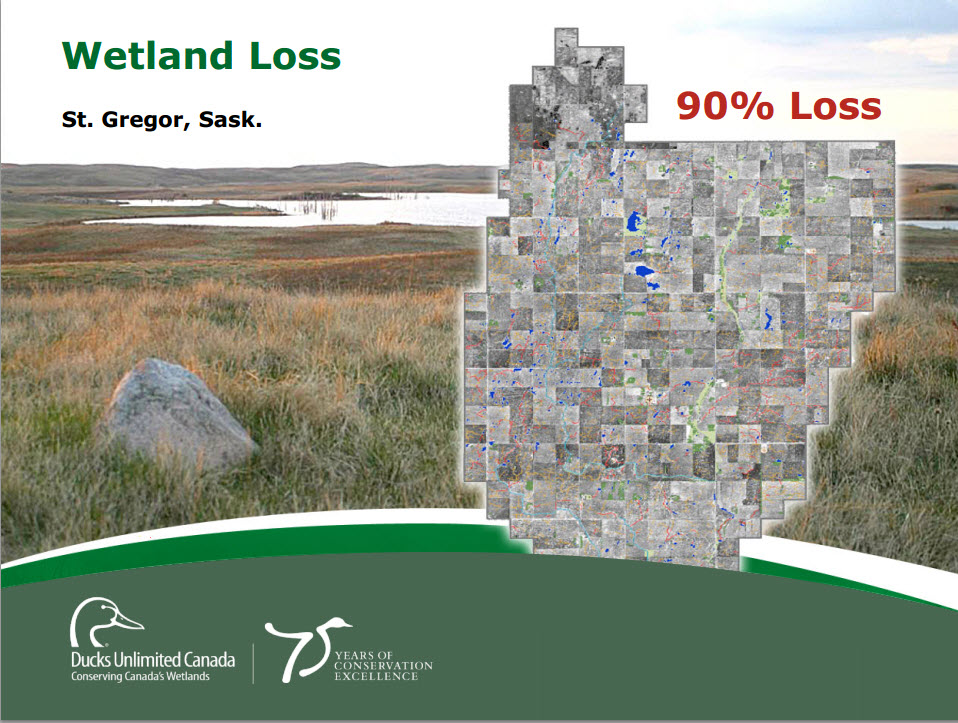

But southern Saskatchewan and southwestern Manitoba – both of which have faced two major flooding events in just three years – about 350,000 hectares of wetland out of a total of 127 million across Canada – have been lost or drained over the past 40 to 60 years.

Wetlands provide feeding and breeding grounds to waterfowl; they store water that could be badly needed in times of drought; and they also store a vast amount of CO2. Losing wetlands means a possible change in breeding and migration of birds, a loss of important water storage and a helping hand in climate change.

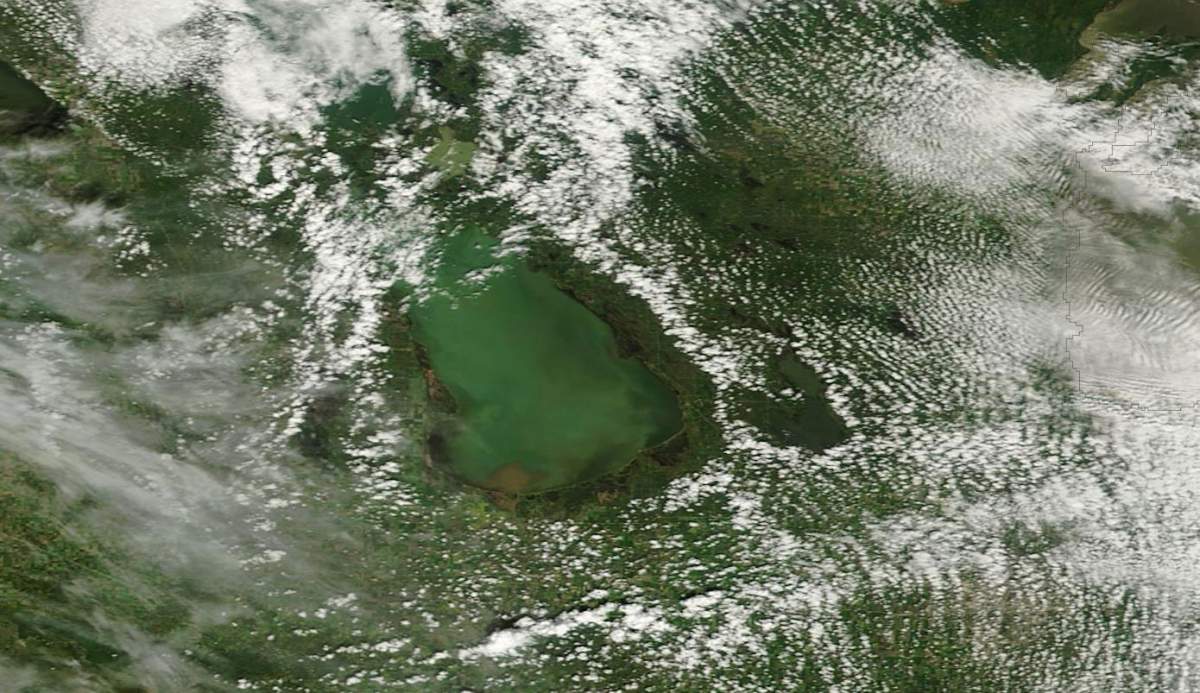

Even the deteriorating state of Lake Winnipeg is due to wetland loss.

Usually wetlands would hold agricultural runoff like phosphorus. Instead, all of that phosphorous flows into the lake, leading to algae blooms and creating an unhealthy environment for fish and other aquatic life. The loss isn’t just to nature: commercial fisheries also operate on Lake Winnipeg.

Healthier wetlands, smaller floods

Bob Grant, Manager, Provincial Operations Manager for Ducks Unlimited Manitoba said his organization has been working with the Manitoba government for about a decade on legislation to protect the wetlands.

“We just need to stop the bleeding,” Grant said. But Saskatchewan, he said, has fallen behind.

“There’s a lot of water coming from Saskatchewan into Manitoba.”

But Saskatchewan grapples with monster floods of its own, the province has started to examine ways to protect the wetlands, as well.

The Manitoba government has published Manitoba’s Surface Water Management Strategy which aims to create no net loss of wetlands. They are in consultations about drafting legislation that would restore and retain wetlands by examining land use.

But for farmers, more wetlands mean less farmland. In fact, farmers will often drain wetlands or fill them in. That creates problems.

READ MORE: 5 of the worst floods in Canadian history

John Pomeroy, Canada Research Chair in Water Resource and Climate Change and director for the Centre of Hydrology at the University of Saskatchewan, has done extensive research on wetlands.

One study found that wetland drainage has a strong impact on stream-flow during floods. The drainage of 96 square kilometres in the Smith Creek wetlands between 1958 to 2008 increased the 2011 flood peak by 32 per cent. Model simulations on further wetland loss are scary: Completely draining the remaining 43 square kilometres of Smith Creek wetlands would have increased the 2011 flood peak by 78 per cent and ramped up yearly flood volume by 32 per cent.

READ MORE: Manitoba bringing in wetland protection

“Wetland drainage seems to have a tremendously powerful effect on increasing or decreasing stream-flow volume and peak flows,” Pomeroy said.

“When they’re intact, it’s like having tens of thousands of small dams all over the prairie landscape, holding back these floodwaters. And so when they’re drained, it’s like breaching tens of thousands of dams.”

Manitoba and Saskatchewan battle spring floods thanks to snowmelt. But this was a summer flood, brought on by three days of rain. And studies show it’s becoming more common.

The wetlands have an added benefit in an area used to battling droughts: stored water.

Pomeroy points to the drought of 2003 and 2004.

“In that drought, one area in the Prairies stayed kind of green…around Elk Island National Park outside of Edmonton – where the wetland is preserved.”

Both Grant and Pomeroy believe that if governments want farmers to preserve wetlands, they’ll need to sweeten the deal.

As for Peters, the future is now. His livelihood is threatened and facing more crop losses is an unimaginable thought.

“I’m almost ready to throw the towel in,” he says. “I don’t know what to do.”

Comments