Kinew James died alone in her cell, pushing a button to call for help.

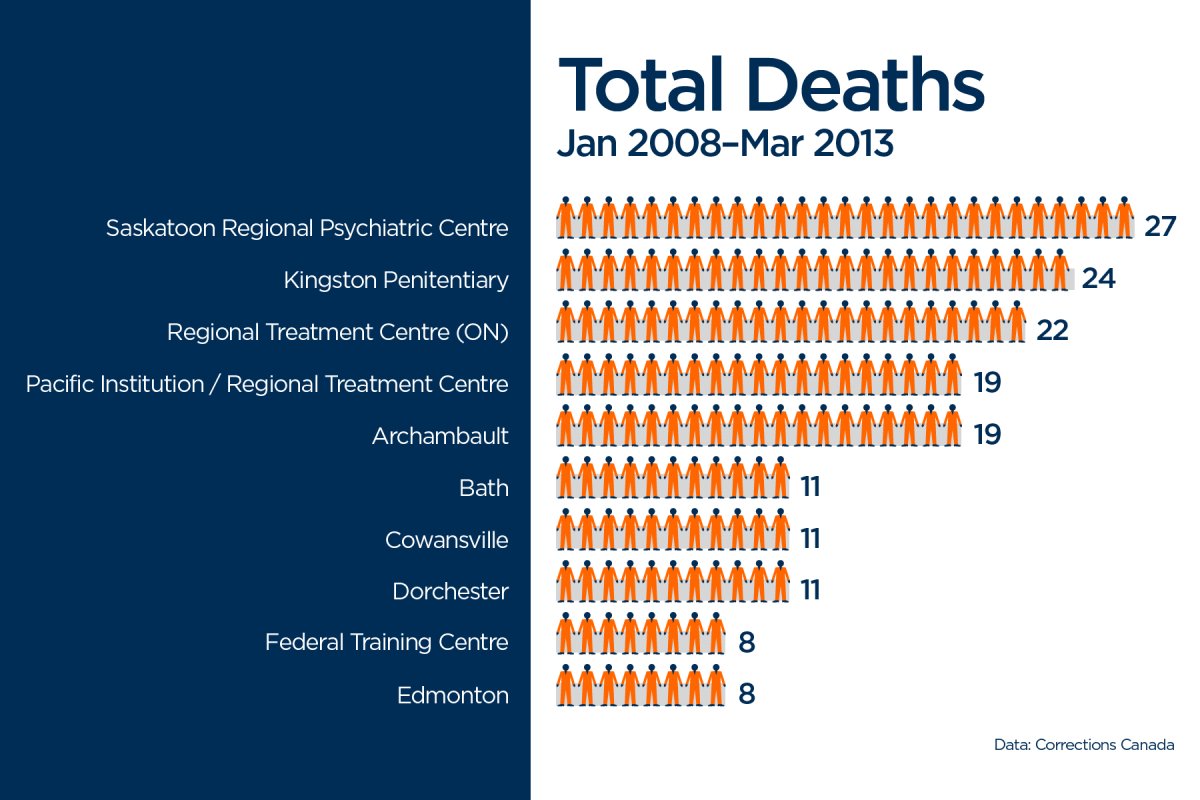

She died at Saskatoon Regional Psychiatric Centre, where more inmates have died in the past seven years than any other federal prison in Canada.

James was never supposed to spend half her life behind bars.

She was sentenced to six years for manslaughter at age 18. But that got extended repeatedly thanks to bad behaviour as she bounced from one institution to another. At 35, she was still behind bars, charged with assault, uttering threats, arson, mischief and obstruction of justice.

“Even before she went in there, she was an outgoing person and spoke her mind – that’s the kind of person she was,” says her mother Grace Campbell.

James struck out on her own early after a rough childhood, moving from place to place.

“She was a runner,” her mom recalls. “I was the same way. But she didn’t know that part.”

On the rare occasion their paths intersected, her mom recalls a skilled cook who stayed connected to her First Nations roots, sent flowers from wherever she ended up.

Campbell remembers visiting her daughter at Kitchener’s Grand Valley Institution for Women. They sat across from each other, ate pop and chips.

James had put on weight in the years she’d been behind bars. She was on pills her mother didn’t recognize.

They spoke briefly on the phone after James was transferred to Saskatoon’s Regional Psychiatric Centre.

‘They should’ve listened to her call for help’

Campbell isn’t sure what happened to her daughter that day in January last year, or why James, who is diabetic, needed urgent help as she repeatedly pressed the distress button inmates use to summon assistance.

“They didn’t listen to her when she pulled that ringer or whatever they have inside her cell. She was just ignored,” Campbell said. “They should’ve listened to her call for help. But they didn’t. …

“I can’t talk any more. I’ll get a sore stomach.”

Corrections Canada said at the time it was looking into the circumstances of James’s death.

“All cell call alarms are treated seriously and designated staff are expected to respond to these alarms in accordance with established procedures,” Corrections spokesperson Sara Parkes said in an email.

On one hand, it stands to reason that if you put the prison system’s sickest and most vulnerable people in one place, that’s where you’ll see the most deaths and violence.

This is “where the most problematic people in the prison system get sent to try to manage their problems,” said Sandy Simpson, a forensic psychiatrist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

“You can never eliminate those violent events occurring because that’s often the reason the person is there.”

But these institutions are supposed to offer better care than anywhere else in the federal prison system.

“Regional Treatment Centres (including Regional Psychiatric Centre) are 24-hour, accredited mental health facilities that provide intensive interdisciplinary treatment to offenders with mental and physical health care needs in safe and supportive environments,” Parkes said in an email.

Inmates are sent there “when it is determined that their mental health needs cannot be met at a mainstream institution or that they require more intensive/in-depth assessment, interventions and/or treatment.”

But at the end of the day, these facilities are still prisons.

“The Correctional Service of Canada knows these are vulnerable people. They’re supposed to have a heightened level of care,” says prison watchdog Howard Sapers.

But “responses to people in distress, a medical emergency … are far too security-driven. It’s an inappropriate first response.”

There should, he added, “be another whole series of response that wouldn’t involve riot squad-dressed correctional officers going in and using force.”

In examining staffing levels in 2011-12, Sapers found almost a third of Corrections Canada’s psychologist staff complement was either vacant or staffed by people not sufficiently trained for the jobs they were doing.

‘The medical staff comes in afterwards’

Guards working in federal prisons get two days in class learning about mental illness. At least, some of them do: About 8,800 got the training between 2007 and 2013.

The course provides “an overview of various mental health issues as they pertain to the mandate of CSC and to staff’s individual role in interacting with and assisting offenders with mental disorders,” Parkes said in an email. She added in a subsequent email, “Both the initial and refresher training for staff are designed to increase awareness and specific skill sets to identify and intervene when offenders are at risk for self injury or suicide.”

Union head Kevin Grabowsky characterizes it as more of an online course.

Do correctional officers have the skills they need to deal with these inmates?

“There’s a loaded question. I mean … so many people want us to be everything. And we already kind of take on so many different hats – I mean, we’re the first responders … You can’t ask us to have training as a psych nurse and want us to be the security officer at the same time.”

But it makes sense to prioritize security over medical care when dealing with an inmate in crisis, he said.

In a volatile situation, it’s “our training over their training.

“You try to neutralize the area. You try and contain it, whatever it is. And then the medical staff comes in afterwards.”

That’s what worries Kim Pate, national head of Canada’s Elizabeth Fry societies.

“One would think, if they were set up to put mental health first, they would be in a position to prevent deaths,” she said. “What we see is that, generally, the prison component trumps the health component.”

‘This is a place of incredible tragedy’

Kinew James “isn’t the first victim” of the Regional Psychiatric Centre, says Don Worme, the lawyer representing her family.

“That is a place of incredible tragedy.”

Worme says he has a client who’s spent months in solitary confinement at the Regional Psychiatric Centre, “detained in what I believe to be frankly barbaric conditions.”

He chalks at least part of it up to “worker fatigue” – correctional officers stretched to the ends of their ropes.

“The inmates who are detained there … they are not, you know, the nicest folks to have to deal with on a day-to-day basis,” he said. “Unless they are supermen and -women that work there, they will be susceptible to those kinds of frustrations.

“Maybe that can explain, in part, those horrendous numbers.”

These sickest inmates, experts argue, shouldn’t be in prison settings, period.

But the upcoming not-criminally-responsible law, which takes decision-making on offenders’ fate away from medical practitioners, could mean defence lawyers take their chances with the traditional prison system. That would put even more people with serious mental illness in prisons that can’t handle them.

Future, interrupted

Kinew James had plans: She was just months away from release, speaking with her mom daily on the phone about what she’d need when she got out.

They’d talk about where she’d live, the furniture she’d buy, what she’d study at Athabasca University.

In earlier court appearances, James was adamant she bore no resemblance to Ashley Smith, an inmate who strangled herself after years of harsh treatment behind bars in what a coroner’s inquest ultimately determined was a homicide.

James was stronger, she insisted. She’d gotten her high school diploma. She’d make it.

She didn’t.

“I have all her papers and stuff I can’t look at them,” her mom says. “I can’t look at anything.”

With a report from Adam Hearty

Comments