MONTREAL – Is the Quebec charter of values racist? To most commentators, the word is too strong to describe the Parti Quebecois’ proposed secularism bill.

Controversial, certainly. Divisive, probably. Xenophobic, perhaps.

But racist? The term seems to overstep the bounds of polite debate.

“You cannot call anyone here a racist.”

The minister responsible for the bill, Bernard Drainville, said as much in January when he dressed down a citizen who, in his testimony at the hearings on the charter, had called Journal de Montréal columnist Richard Martineau “a racist little journalist.”

“You cannot call anyone here a racist,” Drainville retorted, in the tone of a stern schoolmaster chiding a wayward student.

“I won’t accept it.”

READ MORE: Parti Quebecois unveils details of charter of values

The word “racist” in this context is understood as a slur against an individual: an insult that calls into question his moral character.

We all know that racists are evil people, Drainville seemed to imply, and it is uncivil—if not defamatory—to accuse someone of something so heinous.

But is this actually what the word means?

“…virtually no one is willing to self-identify as a “racist.”

Scholars of race have for some time distinguished between racial prejudice, which is manifested through thoughts and feelings, and structural racism, which is maintained through institutions and practices that advantage a white majority at the expense of racialized minorities.

The former is hard to detect, as openly racist ideas are met with social opprobrium, and virtually no one is willing to self-identify as a “racist.”

But the latter remains pervasive, since majorities continue to maintain their dominance over minorities, particularly in the economic sphere.

Indeed, this dominance is now more insidious today than ever before, since a ban on open expressions of racism hides more subtle forms of discrimination that disadvantage minorities.

Full coverage: Quebec’s charter of values

Furthermore, the prevailing view that racism is a personal defect—a quality that one finds only in exceptionally evil individuals—makes it difficult to criticize structural forms of racism.

“I’m not racist!” is the inevitable cry. “That’s a terrible thing to say. You’re playing the race card!”

This reaction has been used with great effect by the Parti Quebecois to blunt criticism of the charter.

It could hardly be said that Richard Martineau is a racist—he’s more of a contrarian who loves to tweak the nose of politically correct elites.

And while Bernard Drainville does exude the smarmy self-satisfaction of a debating club president, he shows no evidence of animus toward racial minorities.

So it seems natural for them to express outrage at any accusation of racism.

When the charge is made against a collectivity—such as the people of Quebec—the umbrage is doubled. Quebecers are decent people! They’re welcoming and friendly! How can you say they’re racist?

Get daily National news

“Think about racism not as a character defect, but rather as a cluster of systemic inequalities.”

Thus any criticism of the charter from outside the province is immediately met with charges of “Quebec-bashing” and “neo-colonialism.”

But suppose we think about racism not as a character defect, but rather as a cluster of systemic inequalities.

From this perspective, the existence of racism in Quebec, and in Canada generally, is undeniable.

READ MORE: Rest of Canada decries Quebec’s charter, but opposes some religious symbols

Consider, for example, the persistent discrimination that visible minorities face in the job market.

An abundance of evidence from censuses, surveys, and studies points to the fact that people of colour in Quebec are disadvantaged in hiring, pay and promotions.

The unemployment rate of immigrants is twice that of native-born Quebecers, and those with university degrees have an unemployment rate that is three times higher than their native-born counterparts.

The gap between the unemployment rate of immigrants and those of native-born Quebecers is greater than in other provinces, particularly for women.

“Racial disparities in income in Quebec today are in the same ballpark as those of the United States before the passage of the Civil Rights Acts.”

Canadian-born, visible minority men living in Montreal have annual earnings 31 per cent lower than their white counterparts.

In Vancouver, by comparison, the racial disparity in income is 6 per cent, while in Toronto it is 13 per cent.

Immigrants with a university degree who belong to visible minority have median incomes 32 per cent lower than their white, native-born counterparts.

The median income of immigrants to Quebec with a university education is 39 per cent lower than their native-born counterparts—and again, the gap is much narrower in other provinces.

To put this into perspective, black men in the United States in 1950 earned weekly salaries that were approximately 38 per cent lower than those of white men.

Remember that southern states at this time had a legally-enforced system of segregation that was meant to preserve the political and economic dominance of whites.

In other words, racial disparities in income in Quebec today are in the same ballpark as those of the United States before the passage of the Civil Rights Acts of 1964-65.

READ MORE: Quebec charter hearing witness relates mosque experience in testimony

How is it that we have reached such extreme levels of racial disparity in the absence of racially discriminatory laws?

Sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva has identified a variety of employment practices as “smiling face” discrimination.

These forms of discrimination do not explicitly bar minorities from employment, but instead identify particular traits that are considered to be problematic in minority populations, and then use them as a rationale for not hiring them.

Thus African-Americans are construed as “lazy” or “not good team players,” and therefore their resumes are placed at the bottom of the pile on the employer’s desk.

There is ample of evidence of this kind of “smiling face” discrimination in Quebec.

“They’re not like us.”

At a 2008 conference organized by the Quebec Human Rights Commission, presenters related the many different ways in which employers justified not hiring minorities.

“They’re not like us. They’re slow,” one said.

“I don’t have time to make them understand how the business works,” said another.

Others claimed that customers were uncomfortable with employees who had a foreign accent.

Still others complained that ethnic tensions were disruptive in the work place, and therefore refused to mix, for example, employees who were Jewish and Muslim.

According to a study published in 2012, job applicants in Montreal with identifiably “foreign” surnames are over 60 per cent less likely to be invited to a job interview on the basis of their CV than candidates with “Québécois de souche” surnames—even if the two have exactly the same qualifications.

Interestingly, Bernard Drainville acknowledged the existence of such discrimination at the charter hearings, telling the committee that numerous employers had informed him that they refused to hire minority candidates.

“They receive their job applications, and throw them in the trash because they are afraid of receiving a demand for accommodations.”

What makes the proposed charter of values troubling in this context is that it replicates the pettifogging logic of “smiling face” discrimination.

A particular trait is identified that distinguishes minority populations from the majority: the wearing of visible religious symbols.

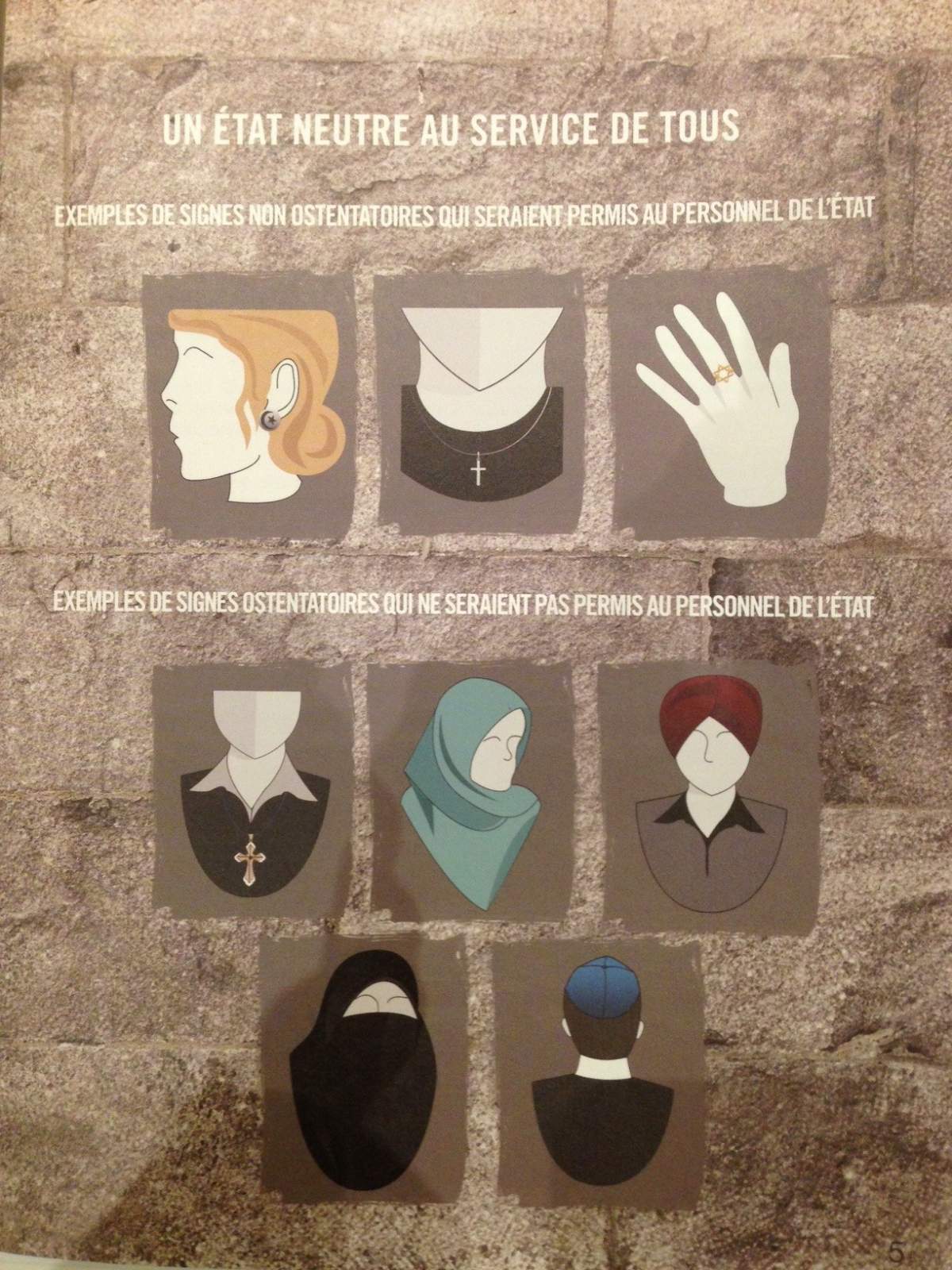

READ MORE: At a glance: Quebec charter of values’ 5 proposals

This difference is then construed as a problem: it supposedly compromises the religious neutrality of the state, promotes fundamentalism, and undermines gender equality.

This problem is then used as a rationale not to hire candidates from racialized minorities or, potentially, to fire them from their jobs.

“Presumably Jewish employees who do not wear a yarmulke will still ask for a holiday on Yom Kippur.”

Drainville claims that the charter will remove impediments to the hiring of minorities because it will allay fears among employers that they will be forced to provide them with religious accommodations.

But he does not explain how a ban on religious clothing will accomplish this—presumably Jewish employees who do not wear a yarmulke will still ask for a holiday on Yom Kippur.

Nor does he recognize that rationales for discrimination are a moving target—employers first identify difference in an ethnic Other, then use a variety of explanations to justify their discrimination.

Religious clothing, in any event, does not rank very high in the reasons why employers do not hire minority candidates.

Furthermore, even though the charter will only apply to the public sector, it will send a clear signal to the private sector that this kind of discrimination is permissible.

READ MORE: Private companies welcome to implement Quebec’s charter of values: Marois

Indeed, it would seem manifestly hypocritical for the Quebec government to ban public employees wearing religious clothing while at the same time prosecuting private firms for doing the same.

The result is that the charter, far from eliminating the causes of discrimination, will only reinforce them.

So is the Charter in fact racist?

From this perspective, yes, absolutely. And we should not be so shy about saying so.

Gavin Taylor is a Senior Lecturer in the History Department at Concordia University.

His views are his own and do not necessarily represent Global News.

Comments