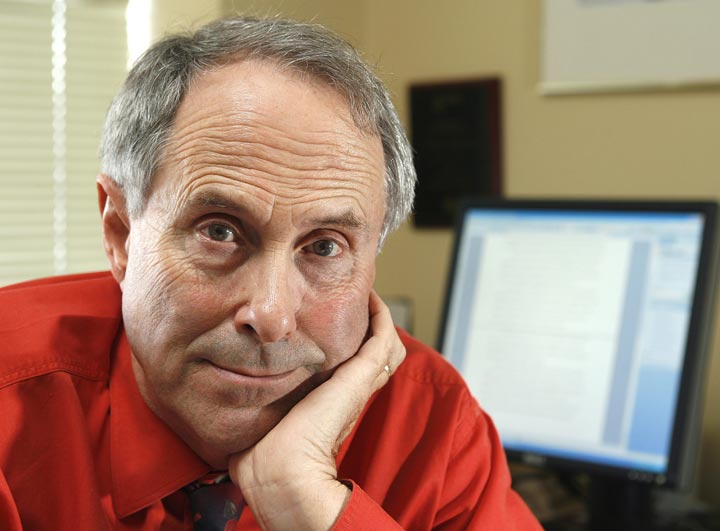

OTTAWA – Tom Flanagan turns 70 this week, and he’s worked in politics on and off for 23 years – including as an adviser to Stephen Harper in his pre-prime minister days.

So now seems as good a time as any to realize he’s been doing it all wrong.

“I probably don’t fundamentally belong in the political world,” he says.

“My communications instincts are terrible, they are always wrong. I’m never right in assessing what’s the right wording or the right thing to say, or what will become a big issue.”

During an hour-and-18-minute lunch of sparkling water, buttered baguette and steak salad – medium – at Ottawa’s Metropolitain restaurant, Flanagan offers a glimpse into why that might be.

“Stephen is a predator. It’s whoever is in his sights,” he says at one point, laughing, in reference to how Harper feels about his political opponents. And, later: “I guess (Harper) decided that if he wasn’t going to be able to reform the Senate, he was going to play politics even more ruthlessly than his predecessors.”

As for recent comments Flanagan made about Harper’s sluggish physique compared to Liberal leader Justin Trudeau’s? “I regret that one,” he says, before adding, “but it’s true.”

He’s managed to fall out with three leaders – Harper, former Reform Party leader Preston Manning and Wildrose Party leader Danielle Smith. But at least Manning talks to him again.

“Three leaders have given me the boot. That must show something. So I mean how long can you keep on blaming them? I’ve come to realize that, as George Costanza said on Seinfeld, ‘It’s not you, it’s me.’ It really is me.”

Last February, Smith cut ties with Flanagan – who managed her 2012 Alberta campaign – when he questioned during a university discussion whether those who view child pornography should be jailed. “We put people in jail for doing something in which they do not harm another person,” he said at the time.

Flanagan later apologized. But the controversy cost him: The prime minister’s office called his words “repugnant,” CBC fired him from its political panel and he retired from his political science job at the University of Calgary after the school’s president condemned his remarks.

But he has managed a comeback – of sorts.

After being dropped from the roster last year, Flanagan was back at last weekend’s Manning Networking Conference, which brought together the who’s who of conservative politics; he’s authored two recent books (“Winning Power” came out in January, “Persona Non Grata” is due in May), and he returned to the university to teach a course in public policy.

Flanagan won’t talk in detail about what happened – something about a “cone of silence” from McClelland & Stewart, the publisher of his next book, which delves into his experience in exile.

All he can say is that it was traumatic, much like the breaks that came before it.

“It is a serious mental thing that you go through,” he says. “I was completely blindsided by this whole thing. Now I feel that I understand what happened, but it was through the writing of the book that I got there.”

Possibly most important, he realized his true calling was that of an “interested observer,” not a political operator.

“It just wasn’t natural for me,” he says. “Something would always happen.”

Beware an ‘inbred’ PMO

During the 2004 election campaign, Harper had an edict: no negative advertising.

It didn’t work.

“The Liberals proceeded to blow us out of the water,” says Flanagan, who managed the Conservative campaign that year.

“We all drew a lesson from that. It wasn’t going to work to be the Boy Scout.”

In fact, all three of the new leaders he’s worked for started off by saying they would not use negative advertising.

“But they all learned sooner or later that you have to be prepared to fight back. And then once you’ve accepted the necessity of fighting back, then it’s just another short step to say, like Jack Reacher does, ‘Well I’ll get my retaliation in first,'” says Flanagan.

“That’s just the bitter experience of politics as it is.”

While he’s said the Conservatives’ personal attacks on Trudeau aren’t working, Flanagan doesn’t believe the Liberal leader is being all that positive himself.

- Alberta to overhaul municipal rules to include sweeping new powers, municipal political parties

- Canada, U.S., U.K. lay additional sanctions on Iran over attack on Israel

- No more ‘bonjour-hi’? Montreal mayor calls for French only greetings

- Trudeau says ‘good luck’ to Saskatchewan premier in carbon price spat

“He’s doing a good job of persuading people that he’s rising above negativity,” he says. “Their message is quite obviously negative about Mr. Harper and the Conservative party.”

But for Flanagan, there is politics, and there is policy – and sometimes politics doesn’t belong.

He finds the government’s recent partisan stance on not bringing opposition members to Ukraine “regrettable.”

“It’s sad that this is happening. I thought it was a great moment when Mr. Harper brought the opposition leaders with him to the Mandela funeral. I personally would like to see more of that,” he says.

Flanagan notes that Harper has made an effort to expand his team beyond long-time loyalists, by bringing in former chiefs of staff Guy Giorno and Nigel Wright.

But since the Senate scandal, that has changed.

“In a time of a lot of stress, when you’ve got huge problems, you feel you’ve got to get people that you know you can rely on,” he says.

Former director of communications Dimitri Soudas is back as the Conservative Party’s executive director; Jenni Byrne has gone from the party’s director of political operations to deputy chief of staff, and long-time staffer Ray Novak has taken over the chief of staff role.

“I hope that won’t be permanent,” Flanagan says.

“It becomes too inbred, and everybody thinks the same. And everybody’s tied together by unconditional loyalty to the leader, and so might not canvass the options thoroughly.”

As a one-time chief of staff to Harper, Flanagan says he can understand Wright’s conundrum on the Senate file.

“I don’t know if he caused the problem. He ended up taking the blame for the problem,” says Flanagan. “The style of the government is adversarial and not wanting to admit mistakes. One thing leads to another.”

Flanagan says “it’s possible” that Harper didn’t know about Wright’s final decision to write the $90,000 cheque to Senator Mike Duffy.

“I find it hard to believe that the prime minister would not know of the earlier attempts, which involved transferring money from the party to Mike Duffy. He may not have known the precise amounts, but it’s hard for me to believe he wouldn’t know something of that type was happening.”

At the very least, he understands the pressure Wright was under.

“I hope nobody ever probes everything I did as campaign manager and chief of staff,” he says, biting into a roasted tomato.

“You do things that, you know, are kind of edgy. And that happens fairly frequently, so you get in the habit of pushing the envelope.”

Harper secretive, decisive

When Harper was leader of the Canadian Alliance in 2002, Flanagan published an article about the party’s leadership.

“I didn’t think it was controversial,” says Flanagan. “But when (Harper) read it he said, ‘Tom, it’s always dangerous to share information.’”

It was a sign, perhaps, of things to come.

Harper froze him out of the inner circle when Flanagan published his 2007 book Harper’s Team. Later attempts by the late campaign director Doug Finley and others to bring Flanagan back into the fold ended with unreturned phone calls.

“There was never an official ending. He just wasn’t in touch anymore,” Flanagan shrugs.

“I find Canadian politics frustratingly secretive, but Stephen carries it probably further than most.”.

Born in the United States (“I like to say I’m the only person who’s lived in both Ottawa, Illinois, and Ottawa, Ontario”), Flanagan arrived in Calgary in 1968 to work as a professor.

He got involved with Manning’s Reform movement in the early 1990s, when he used to attend “egghead” lunches with faculty and graduate students at the university.

“I didn’t work for Preston for very long before that broke down,” he says. “I couldn’t really tolerate a lot of the political compromises that in retrospect I see that he had to make.”

It was through Manning, however, that he met Harper, who was working as the Reform party leader’s policy director. Flanagan went on to manage two of his leadership campaigns.

“You always knew that Stephen was going to be something,” he says. “I wouldn’t have said he’d necessarily be prime minister, but something. Something big.”

It was Harper’s smarts combined with a “very acute strategic sense” that really impressed Flanagan.

“He can read a research paper and understand it and discuss it in those terms, but then he can also say, ‘Ok, here’s what we could achieve under the circumstances and here’s how we go about it.'”

Another factor that made its mark on Flanagan was Harper’s confidence.

“Sometimes he’s wrong, but he’s decisive. That’s really important. So people trust his judgment. I mean, I did,” he says.

As for what’s next for the party, Flanagan doesn’t believe there is a natural successor in line to replace Harper.

“There is no obvious heir apparent, like Paul Martin was the obvious heir apparent to Jean Chretien,” he says.

The rumoured replacement, Employment Minister Jason Kenney, is a “strong candidate” but by no means a shoo-in, Flanagan says. For one thing, he represent Calgary – just like Harper.

“We’re going to have to get through the next election,” he says. “If Stephen is returned, then it’s several years down the road at least. And if the Conservatives don’t do well, and they’re defeated, then he probably would resign. He almost certainly would resign. Then the race will come.”

But as he sips an espresso, Flanagan happily notes he won’t be involved.

“I’m not seeking any favours. I’m not working for anybody,” he says.

“The only person I can embarrass is myself.”

The original version of this story stated Flanagan said there was no harm in viewing child pornography. In fact he questioned whether those who view child pornography should be jailed and said it does not harm another person.

Comments