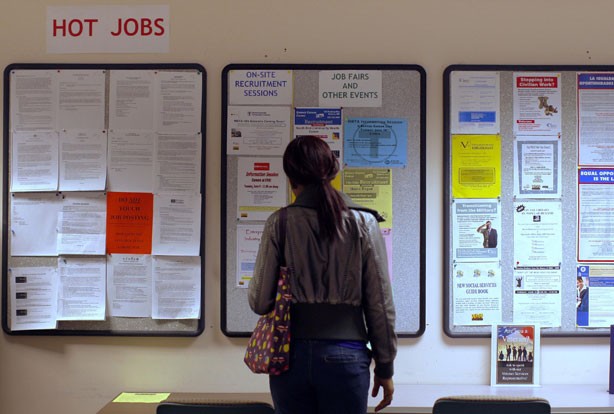

Friday’s employment numbers may’ve been lacklustre. But the job search is far bleaker for new Canadians: Years after the recession officially ended, you’re still more likely to be out of a job if you’re an immigrant.

READ MORE: Key takeaways from the latest jobs numbers

But the picture changes dramatically depending where in the country you are: In Quebec, which for years boasted the worst immigrant unemployment in the country, university-educated new Canadians had a much easier time finding a job last year than the year before.

And, of course, these unemployment stats don’t include the legions of new Canadians who are underemployed – the stereotypical PhDs driving taxis or pouring coffee.

Get weekly money news

The Toronto Region Immigrant Employment Council has spent a decade trying to help new Canadians enter the workforce. Last year, says Executive Director Margaret Eaton, they matched 1,300 immigrants with professional mentors.

“Somehow in Canada, it’s a funny contradiction: We pride ourselves on being so open to newcomers, but unfortunately if someone is coming here and they haven’t had that piece of Canadian experience, it goes against them” – consistently enough that Ontario’s Human Rights Commission made it a violation of human rights for an employer to use that reason not to hire someone, Eaton said.

The federal Conservatives have vowed to dramatically revamp the immigration system, matching applicants with jobs before they even arrive. But in the meantime, advocates have been arguing for better integration services, and less restrictive rules around credentials.

This matters for more than compassionate reasons: It costs the economy when people’s skills aren’t fully exploited. And it hurts the country, economists have found, when people brought here to fill badly needed jobs aren’t able to do so.

“If immigrant wage gaps and excess unemployment were completely eliminated,” a December, 2011 Royal Bank of Canada study estimated, it would mean more than $30-billion in additional earnings – about 2 per cent of GDP at the time.

“It’s an untapped resource for our community,” Eaton said. “Fourteen per cent of these highly skilled immigrants … that’s such a waste of talent. That’s such a missed opportunity for us.”

Comments