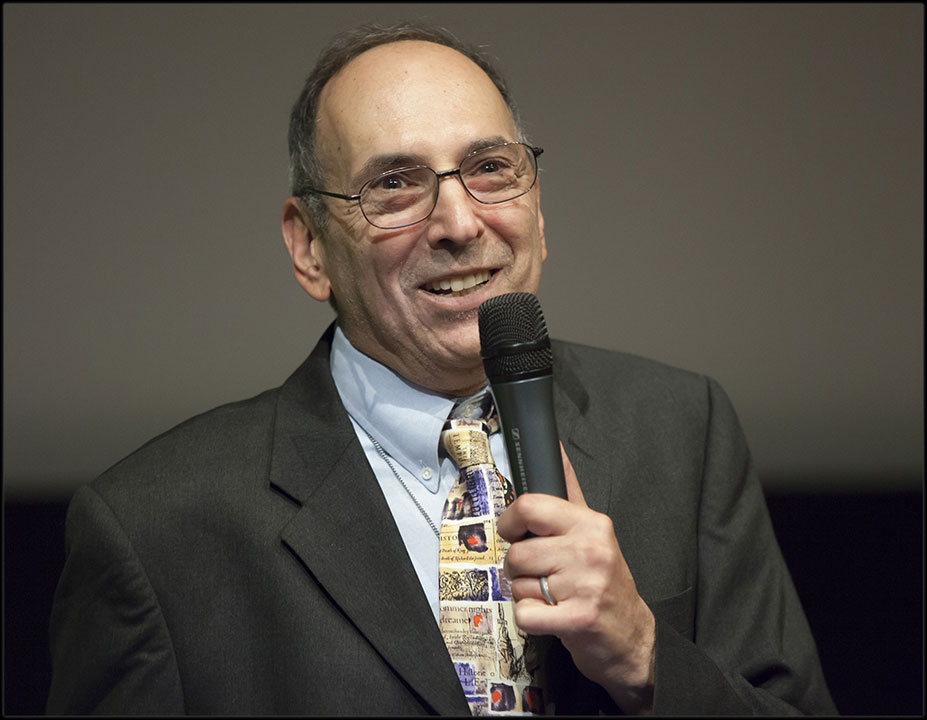

TORONTO – Even though he waited almost 917 hours and 28 minutes — almost 20 years — to discover his first comet, David Levy doesn’t consider himself a patient man.

Since his first discovery, Levy has gone on to discover a total of 22 comets, nine while using his own backyard telescopes. But he has a lot of telescopes: 17 in all.

It’s not his knowledge of the night sky that has led to his discoveries, but rather his understanding of what a comet looks like, which is fuzzy and usually blue. Once he spots that, he checks with maps of the sky to ensure that he’s not seeing some other astronomical object like a galaxy.

Comets are often referred to as “dirty snowballs,” as they are comprised of ice and dust. The tail of a comet results from the solar wind evaporating the frozen gases and dust as the comet nears the sun.

Born in 1948 in Montreal, Levy now lives in Arizona with his wife Wendee. It wasn’t that he didn’t want to remain in Canada. However, a comet hunter benefits from dry, dark skies and Arizona offers some of the best dark sky sites in the world.

What made him want to hunt comets?

Surprisingly, Levy doesn’t have a background in astronomy. He received a Bachelor of Arts from Acadia University in 1972.

“I’m a fraud,” Levy laughed. “You have no business asking me anything about astronomy.”

“I picked it all up by observing, by reading…and doing those things.”

When speaking in Toronto earlier this week, Levy credited his brother for introducing him to astronomy after he dragged him out of the house one night to look at the Big Dipper.

His love of astronomy led his parents to enroll him in a science summer camp. One day his camp director announced that the boys would have to do a science project.

“I want you to come up with a project that is challenging,” the camp director told them. “I want this project to continue for the rest of your lives.”

“I’ll never forget what he told us,” Levy recalled.”‘Failure,’ he said, ‘is the great teacher.'”

Levy did a project that year, but not one that he was particularly happy with.

That September, however, Levy started high school in Quebec, where he faced a French proficiency test. Levy knew he’d be asked about his career goals. Walking to school, he fretted about what he’d choose. Then he recalled the recent discovery of Comet Ikey-Seki.

Levy walked into the boardroom of Westmount High and faced his French teacher, Mr. Hutchinson. When the question was asked, Levy recalled, “I sat as straight as I could and I had a big smile from ear to ear, and I said, ‘Monseiur Hutchinson, je veux decouvrir une comete. Mr. Hutchinson, I plan to discover a comet.'”

His teacher was wary. But jokingly added that Levy had 20 years to discover a comet or his mark would be reduced.

Levy started searching for comets on December 17, 1965. He discovered his first comet on November 13, 1984, almost 18 years and 11 months later.

However, it would be a discovery with partners Eugene and Carolyn Shoemaker that would make Levy one of the most famous astronomical names in the world.

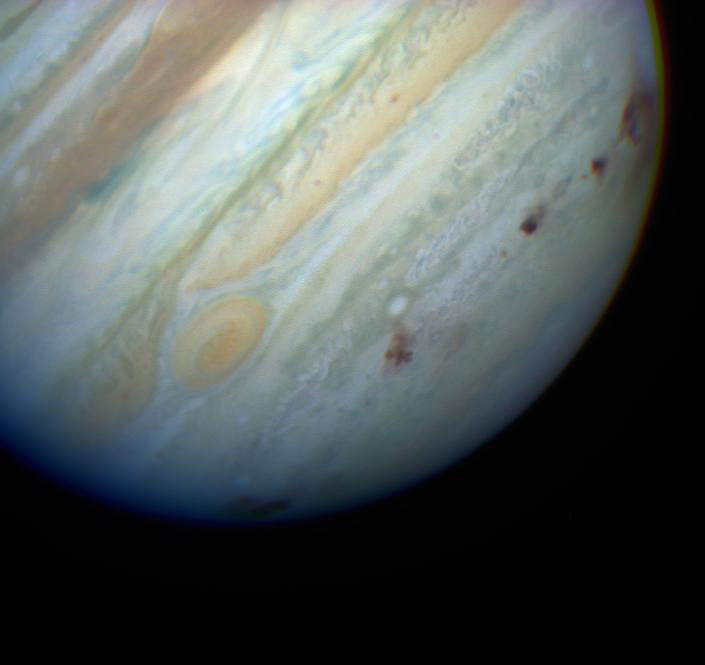

Shoemaker-Levy 9, or SL9, put on the most dramatic show ever witnessed in our solar system. When the comet was discovered in 1993, it had broken up into 21 pieces, and each one of them was set to collide with Jupiter in July 1994. The result of the collision was breathtaking: each piece exploded in Jupiter’s cloud tops. Even more spectacular was that the scars they left could be witnessed in even the smallest ground-based amateur telescopes.

But there was far more to just a show that Jupiter put on: it is widely believed that comets brought water to Earth, giving the basis of life. Comet SL9’s crash into Jupiter was like the solar system saying, “This is how it happened. You can watch, but from the safety of Earth,” Levy said.

The effects of the collision are still being felt on Jupiter. Almost 20 years after the impact, ESA’s Herschel space observatory found that Jupiter still has water in its atmosphere.

What now?

Levy may be getting older, but he hasn’t given up comet hunting. Though the thought had once occurred to him.

Years ago he asked his wife if he should stop looking for comets.

“Does it make you happy?” she asked.

“Oh, yes,” he responded.

“Then why stop?”

Comments