A provincial program that tracks the spread of COVID-19 infections throughout Ontario is now being expanded to include influenza in its reports.

The expansion of the wastewater surveillance project, launched by a team at Western University in London, Ont., is part of an additional boost of $18.7 million in provincial funding for Ontario’s COVID-19 wastewater surveillance initiative.

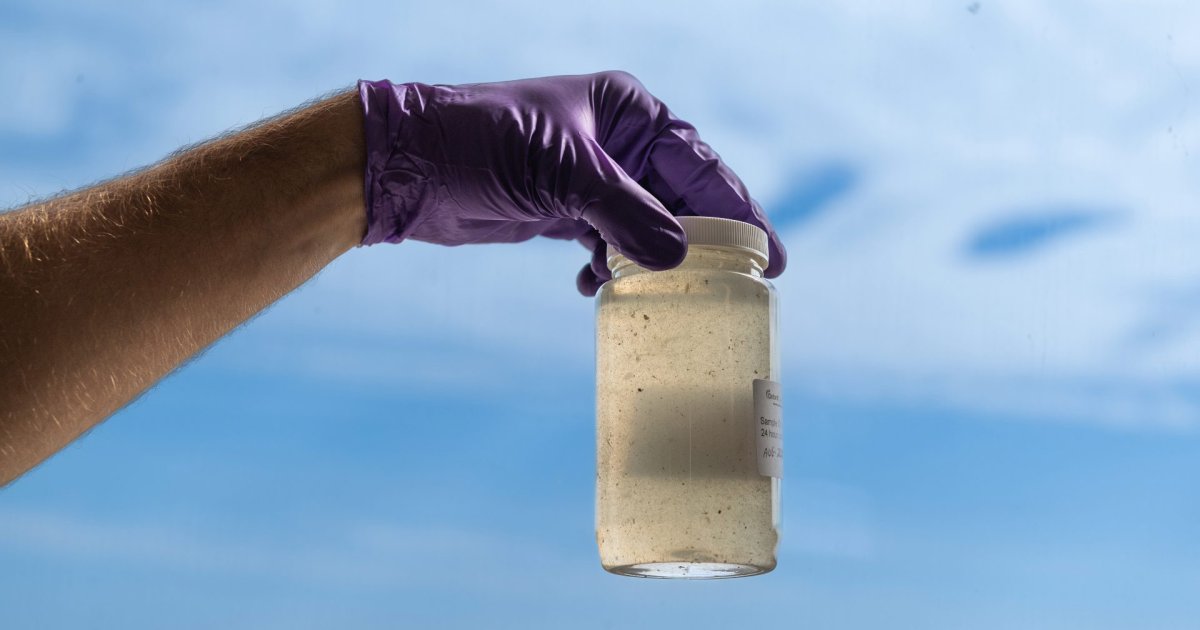

Led by a consortium of universities, the initiative, which was launched back in 2020, surveils sewage in monitoring the location of emerging COVID-19 infections.

“There’s 14 different groups across the province that are contributing to wastewater surveillance,” said Chris DeGroot, assistant professor in the department of mechanical and materials engineering at Western. “We’ve been doing wastewater treatment plants in London, as well as Woodstock, Sarnia, Caledonia and Hagersville. … It’s gone from five sites down to three sites in London now, but we’ve increased our frequency.”

According to the project, analyzing the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater, shed through human waste, provides public health agencies with insights into disease trends.

The expansion comes as two variants of the virus have captured the attention of scientists, warning of the start of a possible new wave.

“With reduced public reporting of cases, conventional surveillance methods for tracking the spread of SARS-CoV-2 are now unreliable,” DeGroot said. “Wastewater surveillance can offer accurate insights into the community prevalence of COVID and other respiratory viruses, especially when it is combined with clinical data.”

DeGroot, who is also the lead investigator for the project, told Global News that it’s been an interesting experience to see how the data from the project has been used these past couple of years.

Get weekly health news

“Early on, when we first started tracking this, we were really looking at winter waves of COVID and how they were beginning and ending which public health officials were more interested in using that information to inform policy changes,” he said. “It’s really shifted since then to being more of an informative tool.”

“People in the community seem to also like having that data available to them,” DeGroot said.

“They use it to decide what sorts of activities they’re comfortable with, looking at when there is a rise in cases, maybe defining when they should go get their next booster and all kinds of things like that,” he said. “So, people are using the data, public health is still monitoring it, and it’s still a great tool to see what’s going on locally.”

In comparison with individual PCR testing, he said that community surveillance wastewater testing is more accurate and cost-effective.

“Doing individual PCR tests on people who are infected, it’s quite costly,” he said. “One PCR test we can do on wastewater is just so much cheaper than trying to do PCR tests on the entire population which we saw through the Omicron wave. It just isn’t practical to maintain that.

“In terms of rapid antigen testing, people are using these at home, but there’s very limited ability to report positive tests on rapid antigen,” DeGroot continued. “Wastewater testing is really great, because it’s automatically a snapshot of the entire community, and we can do it at a relatively low cost compared to any sort of clinical testing.”

He added that the researchers are also able to look at different variants of concern in the wastewater, something he said is more difficult to do when relying on clinical testing.

“It’s just another source of information that people can use to better inform their actions,” he said.

Now, with the recent expansion to include tracking for influenza, the project will also hold a particular focus on strains such as H1N1 and H3N2.

DeGroot said that these strains account for a large portion of Ontario’s annual flu outbreaks, saying that “early detection of their trends can help mitigate the risk of outbreaks using targeted public health interventions like immunization.”

But the project comes with a deadline of March 2024.

DeGroot said the researchers are hoping the project will continue “indefinitely,” but they’re remaining optimistic.

“We’re hoping that wastewater surveillance will just become a routine part of public health monitoring, but at this time we don’t really know what happens after March,” he said.

As students and families prepare for another school year ahead, Degroot said that according to recent data samples, “we’ve been fortunate that COVID levels in wastewater, pretty much across the province this summer, have been low compared to historical data that we’ve collected.”

“As we head into the fall season and back to school, some sites have started to notice the levels and wastewater heading up already,” he said. “Here in London, we’re still maintaining a fairly low level in wastewater. There’s been a slight increase over the last week or two, but nothing, nothing to indicate a new wave has really taken off in London.

“That being said, now that we’ve seen it in other communities in Ontario and we have the back to school coming, I do expect that fairly soon we will start to see it in our wastewater here in London as well,” Degroot added.

Comments