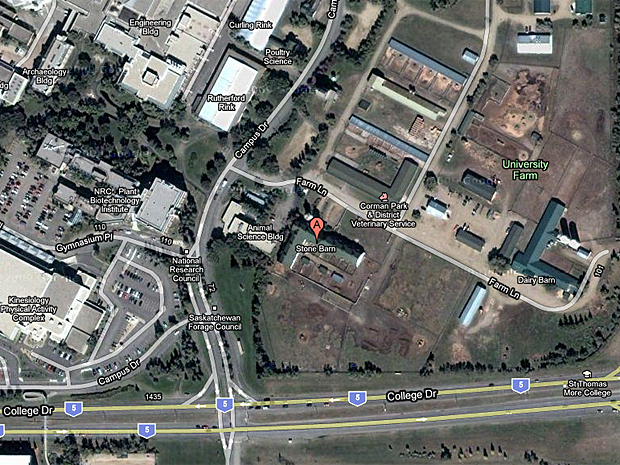

The University of Saskatchewan’s iconic stone barn — the 100-year-old structure seen from College Drive — closed this month after engineers deemed the building unsafe.

The barn closed Sept. 10 and university officials aren’t sure when it will reopen. In the meantime, the two dozen or so calves housed in the barn have found shelter elsewhere.

"The stone barn is one of the most iconic structures on campus," said Colin Tennent, associate vice-president of facilities management and the university’s architect.

Built between 1910 and 1912 by the same firm that designed many of the university’s signature buildings, the barn once stood alone on the prairie. Over a century, the

U of S campus grew around the barn, Tennent said.

The building’s south side, where the freeze cycle has been particularly hard on the structure, has experienced serious wear and tear, Tennent said.

The building won’t collapse in on itself — the floor is very sound — but officials are worried the building could lean too far in one direction, Tennent said.

The stone pilasters — the pillars embedded in the walls — and the trusses in the barn’s large loft have weakened, he added.

"This does not mean the barn is going to collapse, but there are concerns about the integrity of the structure," Tennent said.

An eight-foot base of granite circling the barn, the green roof and towering silos of the L-shaped stone barn — also sometimes called the Main Barn — are instantly recognizable to Saskatoon residents.

"It’s a rich part of our heritage on campus, and something we’re concerned about preserving," Tennent said.

A report completed 10 years ago found the barn would eventually need major restoration. That report recommended the U of S do another structural review in 2010.

The recent review discovered several trouble spots in the building, which led engineers to recommend closure, Tennent said. The calves were moved into sheds elsewhere on campus, while the feed and equipment stored in the barn have also been moved.

Though old, the barn was still used regularly by the college of agriculture and bioresources, said dean Mary Buhr.

"There are nice big stalls in there where we could keep an eye on animals for whatever reasons we need to," she said.

"It’s not a highly technical facility, but we used it."

The closure is an inconvenience, but not a complication that cripples the college’s animal and poultry science department, Buhr said.

"It’s not a devastating blow to us — research mostly happens elsewhere — but it’s definitely an inconvenience," she said. "The closure wasn’t planned, so it caused a flurry of activity."

U of S engineers continue to assess the building, and the university plans to hire outside experts for a thorough evaluation, Tennent said.

"We want to make sure this thing is strong and will stand well into the future," he said.

The university could reinforce the barn’s weak points, allowing the barn to reopen, before a larger, more permanent solution is found. But the cost of ensuring a long life for the barn isn’t known, nor is the cost of a short-term fix.

"We don’t anticipate it’ll be an expensive project just to stabilize the structure," Tennent said. "What would be expensive is the complete refurbishment for the use well into the future."

There is no timeline for the refurbishment. The timelines and cost estimates will be included in a future report.

"In order to restore the barn, there has to be considerable decision-making and money raised to move forward," Buhr said.

"I’ll say there is a will to do the best we can to refurbish the old lady and make her grand again."

Comments