Edmonton police say violent crime continues to increase at an “alarming” rate in the city and that EPS data connects this to 2019 changes to bail made federally under Bill C-75.

“There’s causation and correlation,” said Sean Tout, the Edmonton Police Service’s executive director of information management and intelligence.

“Right now we have a correlation. We know that we had a large change fundamentally in the way that we deal with bail and violent crime in 2020. We know our (community) impacts realized prior to that are significantly less than the impacts that we’re realizing post that.”

Bill C-75 is a huge piece of legislation that the Liberal government passed into law in 2019. The bill made a number of changes aimed at reducing judicial delays, modernizing the bail system and reducing the overrepresentation of racialized people in jails.

There’s been criticism, including from Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre, that Bill C-75 resulted in an overly lenient bail system in Canada.

Statistics compiled by the EPS show the volume of violent criminal incidents in Edmonton increased 16.5 per cent in 2022 over the year before.

“2022 represents the highest number of violent criminal incidents ever reported in a single year,” Tout said Friday.

“This trend continues to escalate in 2023.”

Edmonton’s violent crime severity increased 5.4 per cent over the same time period, police data shows.

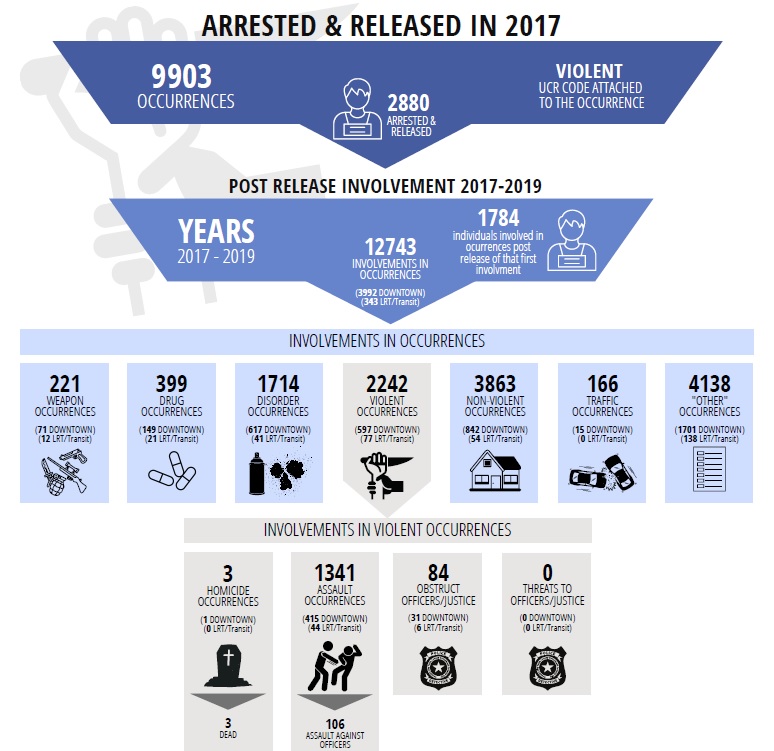

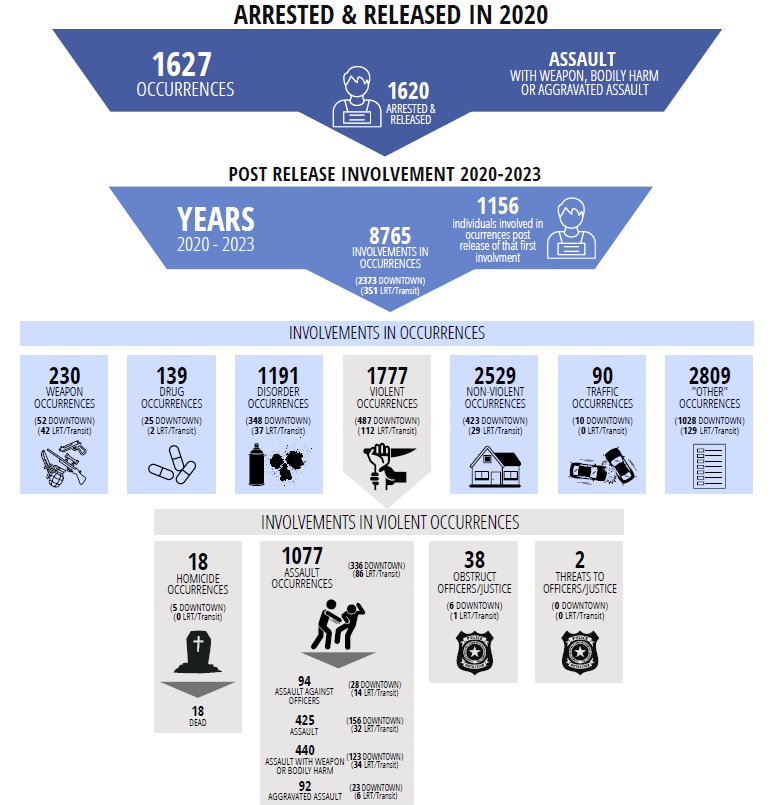

To compare pre- and post-Bill C-75 numbers, EPS looked at the amount of violent crimes committed by offenders in the three years after they had been released — in 2017 and in 2020.

(NOTE: The data includes people who were released following their initial arrest on: bail with and without surety, bail not spoken, show cause, appearance notice, promise to appear, their own undertaking, recognizance with and without surety and released with other reasons such as a caution, referral and/or warning.)

Over three years, after 2017, those released offenders committed 12,743 additional occurrences (including 221 weapons incidents, 399 drug incidents, 2,242 violent crime incidents including three homicides).

Over three years after 2020, those released offenders committed 19,186 additional occurrences (including 440 weapons incidents, 273 drug incidents, 3,637 violent crime incidents including 26 homicides).

“We can see the differences in the volume and severity of post-offence release conduct.”

(NOTE: EPS didn’t use the exact same time period in the comparison. It used data between Jan. 1, 2017 and Dec. 31, 2019 to compare to data between Jan. 1, 2020 and Jan. 25, 2023, so the latter set includes an additional month.)

But a criminologist in Edmonton cautions against attributing crime rates to one factor.

“I think it’s pretty hard to actually create that correlation and causation,” said Dan Jones, chair of justice studies at Norquest College.

Get breaking National news

“We’re coming out of a pandemic, your crime stats are going to be very, very significantly impacted by pandemic lockdowns, all of these different things. I think there’s significantly more to unpack than just Bill C-75.”

He pointed to the economy as another big factor to consider.

“We have to look at these things holistically and significantly unpack all these issues rather than focus on one single thing as the cause of violent crime.”

Jones said locking more people up is a short-sighted solution.

“If you think about it, putting medium-risk people in with high-risk people, it’s like putting your red towels in with your white towels — everything comes out tainted.”

He also worries about these kinds of statistics being released in this way right before an election.

“It provides whatever party you’re talking about the opportunity to attempt to solve this for the community with overarching statements about crime and punishment,” Jones said.

“Sometimes what happens is you start to look at these stats with a very narrow focus and you start to use that as the blame, ‘Let’s take a quick fix and change this and let’s make more people in jail.’

“That’s not the answer. The answer is significantly more complex. You’re talking about social issues, you’re talking about providing people with substance use disorder… with Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, EMDR, all these other things that would actually change this significantly rather than focusing on the single cause of bail reform.”

- Bombardier warns of ‘significant impact’ to travellers from Trump’s threat

- Stepfather of two missing N.S. kids charged with sexual assault of adult, forcible confinement

- Trump threatens Canada with 50% tariff on aircraft sold to U.S.

- Canadians have billions in uncashed cheques, rebates. Are you one of them?

Tout said there is a disproportionately small number of offenders committing a high amount of the crime.

It’s one of the reasons EPS wants the police, court and corrections information systems to be integrated and accessible.

“Police data, courts data and corrections data remain siloed,” Tout said.

“We need to have all the information from all aspects of the criminal justice system linked together. We need to have the police information linked with the courts information linked to the corrections information and then back to the police information.”

Tout said police resources are always tight and EPS tries to pivot to address changing needs.

“We are perpetually evaluating, reprioritizing and deploying our resources for maximum impact.

“But when we’ve got an opportunity to prevent further downstream crimes and revictimization, and the policy and the process of the system itself is hampering us from being as effective as we could be, it’s really exacerbating that problem of how do we resource appropriately to deliver that level of community safety that Edmonton really should expect?”

Tout said that when an Edmonton officer does a “field release,” it is noted in the EPS system. However, when the EPS requests that bail be denied or a hold placed on an offender, the record doesn’t always come back to EPS since it goes into the court system.

Integrating the police, court, corrections — even health — records, Tout says, would allow for a better response, better community safety and more data generally.

“We have lots of very solid criminologists and academics in Canada looking at this and we need to get them the whole of the justice system information so we can do that deep causation analysis and identify better paths forward so we don’t have this repeat victimization,” Tout said.

“There needs to be a collective will.

“There needs to be policy and government support that says: as a system, we must do this. I think our communities would expect nothing less.”

Federal Justice Minister David Lametti previously defended Bill C-75, saying: “The criteria for when accused persons can be released by police, a judge or Justice of the Peace were not changed by Bill C-75.

“Bill C-75 simply brought the Criminal Code in line with binding Supreme Court decisions.”

In Canada, there is a constitutional right not to be denied bail without “just cause.” It’s enshrined in law that the detention of an accused person is justified if it is “necessary to protect the safety of the public, to maintain the public’s confidence in the justice system, or to make sure the accused person attends court,” Lametti explained.

When firearms are involved, the bar for bail can be set even higher. A reverse onus is imposed on the accused when they’re charged with some firearms offences. That means they’ll be detained by default — and the accused will have the responsibility of proving that bail would be justified in their case.

After meeting with his provincial and territorial counterparts in March, Lametti committed to move forward quickly on “targeted reforms” to the Criminal Code that would update Canada’s bail system.

A spokesperson for the federal government said those reforms will address the challenges posed by repeat violent offenders, as well as offences committed involving the use of firearms and other dangerous weapons.

“These reforms must ensure the safety of Canadians and respect the right to reasonable bail,” said Diana Ebadi, press secretary for the minister of justice.

“All ministers agreed that these measures must not undermine the critical work being done to address the overrepresentation of Indigenous, Black, racialized and marginalized people in our criminal justice system.”

EPS data shows that between 2013 and 2022, the total crime rate (per 100,000 population) saw a rise from 7,738, peaking in 2019 at 10,625. That has since gone down to about 9,135.

The Crime Severity Index saw a similar trend.

However, the number of violent crime incidents in Edmonton has risen quite steadily from 2013, noting a spike in 2022. It went from about 10,605 violent criminal incidents in 2013 to about 15,040 in 2022, increasing 13 per cent since 2018. (2022 data isn’t finalized yet as some investigations are still open.)

Edmonton police released this data on the same day the association representing Canada’s chiefs of police is meeting with provincial and territorial premiers to talk about reforming Canada’s criminal justice system.

On Friday, Manitoba Premier Heather Stefanson, who chairs the Council of the Federation, said premiers aim to hear chiefs’ public-safety concerns and their perspectives on how Ottawa should amend federal law, including on bail reform.

There have been requests of the federal government to renew and enhance its Guns and Gang Violence Action Fund, which supports provincial and territorial public-safety initiatives, and to create “reverse onus” measures for certain offences that would require a person seeking bail to prove why they should not stay behind bars.

Comments