For months University of Saskatchewan scientists requested Saskatoon’s COVID-19 hospitalization data from the Saskatchewan Health Authority (SHA) and provincial Ministry of Health.

The USask group wanted to combine it with the data they track, the amount of SARS-CoV-2 genetic material in the city’s wastewater.

With both information sets the researchers would have valuable insight into how the viral load translates into occupied hospital beds, one of the toxicologists who studies wastewater, as well as an epidemiologist, said.

The combined data sets could potentially even enable researchers to predict roughly how many people sick with COVID-19 would need a hospital bed in coming weeks.

It would have been a tool for Saskatchewan’s healthcare system, the toxicologist said. That, in turn, would allow frontline healthcare staff, already burnt out after years of pandemic triage, a chance to prepare or at least to better understand the viral spread that was overwhelming the hospital system with patients.

But government agencies never provided the data.

Emails, obtained by Global News using a freedom of information request, show the USask wastewater team lead researcher toxicologist John Giesy asked various SHA officials repeatedly over four months if his team could access the weekly hospitalization numbers.

- What is B.C.’s Mental Health Act and why is it relevant to Tumbler Ridge shooting?

- YouTube, Roblox say they deleted accounts tied to Tumbler Ridge shooter

- Elections Canada says Freeland broke rule by answering byelection questions

- Air Canada says it saw strong profits despite drop in U.S. travel demand

In one email he specified the team didn’t want data that could identify patients. He just needed the numbers.

Giesy said the wastewater team ultimately abandoned the arrangement because the proposal would have required the researchers to share their data with the government before speaking to the media – and to seek government approval before discussing their findings publicly.

“What they were asking was that they review (the data) and let us know whether they wanted me to comment on it or not,” he told Global News.

Giesy regularly speaks to multiple media outlets to share the team’s weekly updates on the COVID-19 quantities in wastewater in several cities across the province. And the university publishes the teams’ latest findings every week.

He said the researchers have several data sharing agreements with different government agencies and that none have stipulated he cannot speak publicly or require him to seek approval first.

“Here at the university, our role is to discover new things and make that technology available,” he said.

People infected with COVID-19 typically start shedding the virus through their stool before they begin displaying symptoms. Scientists around the world started tracking the level of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in many cities because the quantities of detected viral material can indicate how many people are sick and therefore how many people could require hospital care.

Last February the Government of Saskatchewan switched from reporting COVID-19 information, including hospitalizations, every day to every week, changing again to monthly reports in August.

The changes meant wastewater research became even more valuable since it was one of the few sources of timely information about the pandemic that was publicly available.

Giesy and his team wanted to correlate the data sets to potentially show how many people would need hospital care. And he wanted to track how the new and more infectious Omicron subvariants affect the healthcare system. Previous data relied on older and less infections strains.

Giesy first mentioned plotting the seven-day average of new cases, current cases and hospitalization in an email to a SHA employee on April 19.

Get daily National news

“These plots will let us make some conclusions on the lead time for the three clinical measures, which is what managers need to know,” he wrote.

An SHA employee responded that day, saying she had submitted the request on his behalf.

The emails show Giesy didn’t hear back for more than a month after the initial exchange in April.

In June he wrote again, saying the team is still interested in acquiring the data. “We… are working with modelers at the Public Health Agency of Canada to develop relationships between admissions to hospital for COVID and the number of copies of the virus in the wastewater,” he said, adding that it could be expanded to other viral infections in the future.

He pointed out they wanted the data in aggregate “so we do not believe there are any issues of privacy or ethics to overcome.”

“It seems this data is already available so it would not be a large amount of effort to assemble it…”

The SHA employee, a scientist, forwarded the message to an SHA senior contract specialist, who responded about 20 minutes later saying she had an agreement drafted that was sitting with the Ministry of Health.

The data, she explained, is sourced from the provincial public health information system, Panorama, of which the ministry is the trustee.

“Even if what we are providing to the researchers is in aggregate form, we always need to go back to the data source(s) and have them decide what role, if any, they feel they have in such an agreement.”

Later that day the contract specialist sent another email with the draft attached – but it wasn’t included in the freedom of information request.

She said she’d be on vacation and cc’ed her director

The email stated the agreement included the University of Regina (UoR) as well.

Tzu-Chiao Chao, a UoR researcher, told Global News the Regina team had put the agreement on the “backburner” since the summer and hadn’t looked at it in months.

He said he was hoping to get more clarity from the SHA on what information researchers could and couldn’t share.

A month later, though one day before the employee was set to return to the office, Giesy emailed a USask contracts specialist to ask if there had been any progress.

“I have heard nothing for several weeks,” he said, on August 18, 2022 – almost four months since he first brought the matter up.

The university specialist said they were still waiting for the SHA employee to return.

The freedom of information request didn’t yield any later emails.

Epidemiologist Nazeem Muhajarine, who also works at USask but not with Giesy, said he was surprised to learn hospitalization data are not available to the wastewater researchers.

“We need to be able to provide data threads from different sources at different levels,” he said, “to be able to tell not only (the) larger story that pertains to groups of people and places, but (also a) more granular level of detail that that that relates to people like hospitalizations, ICU beds and so on.”

Muhajarine specified the wastewater data are trend data – that they show whether the overall amount of infections are increasing or decreasing.

But he said it, combined with hospitalization numbers, could provide key insights into the levels of community transmission.

Without the weekly data to determine infection rates, Giesy and his co-authors of a report were forced to rely on the provincial hospitalization numbers, which the health ministry releases monthly

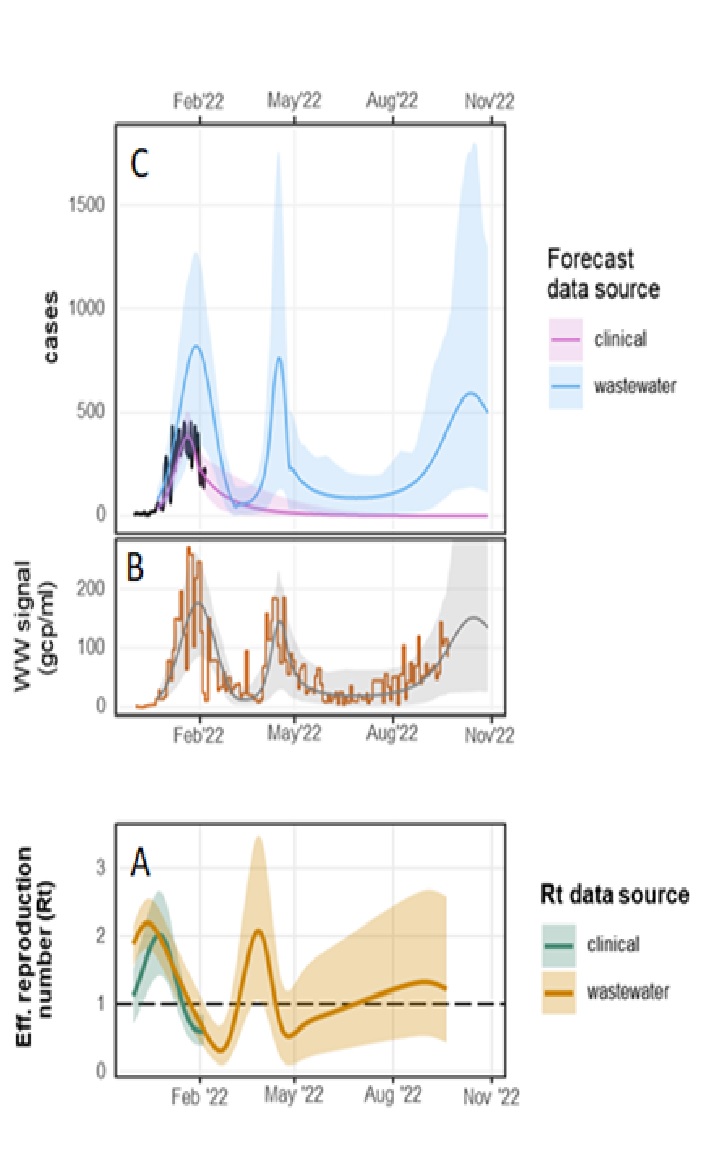

The charts below, which Giesy shared with Global News, show the wastewater data measured against the provincial hospitalizations.

The space between the lines and the shaded areas represents the confidence interval – within which scientists would expect new data to fall if their hypotheses and original data are accurate. The more specific the data, the more accurate the findings should be –meaning the closer the shaded areas are to the lines.

“What you can see are what we put on as confidence intervals and you can see they’re pretty big,” Giesy said.

“So that means our accuracy is not that great.”

Giesy said he didn’t know why the data wasn’t provided, wondering if the SHA and health ministry were modeling the hospital admissions on their own.

The health ministry’s monthly COVID-19 situation reports reports, which provides the data for COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations and deaths for COVID-19, Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) and influenza, uses the USask researchers’ findings for Saskatoon, North Battleford and Prince Albert.

In a statement, an SHA spokesperson said “(p)rotocols around the disclosure of information, particularly data, are standard in SHA contracts. This proposed agreement is no different.”

“Wastewater surveillance has been known to fluctuate significantly week-to-week. This type of information offers no guidance on how, when or where someone should seek care,” Doug Dahl wrote. (The emphasis is his.)

“Directly linking this data with data on hospital capacity must be done with the utmost caution to avoid inappropriately dissuading members of the public from seeking necessary care, including emergency care.”

Dahl also wrote that to exclude the SHA and ministry from the disclosure process “presents risks to our clients, departs from SHA’s typical practice of including disclosure provisions within its contracts and would not appropriately reflect the roles and responsibilities of the parties to the agreement.”

Muhajarine said the failure to share the data shows how the Saskatchewan government politicized COVID-19.

“This hospitalization data (and) case data are people’s data. They belong to people of Saskatchewan. They don’t belong to the premier of the province. They don’t belong to the cabinet,” he said.

“We need to use this data to benefit people of the province, and that is actually what has not been happening since about (the) early months of this year.”

Global News asked Saskatchewan health minister Paul Merriman for comment.

He did not respond by deadline.

Muhajarine told Global News wastewater analysis, combined with hospitalization data, could also provide crucial monitoring of other illnesses like influenza.

The wastewater researchers have already begun tracking influenza and RSV.

Even if the government didn’t make the hospitalization data available (or not available under acceptable terms) because of all the political issues around masking and other public policy matters, Giesy said, he didn’t expect that to be issues for tracking the flu.

He said he hoped the team would be able to get the numbers.

“We’re researchers,” he said.

“And what I try to do is, where possible, bring technology to bear on socially relevant questions.”

Comments

Want to discuss? Please read our Commenting Policy first.